Math Is Fun Forum

You are not logged in.

- Topics: Active | Unanswered

#1 Re: Dark Discussions at Cafe Infinity » crème de la crème » Today 18:45:44

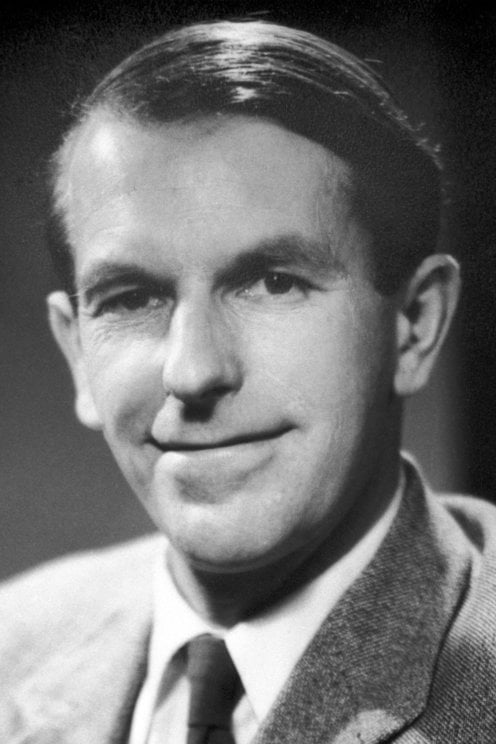

2429) Fredrick Sanger

Gist:

Life

Frederick Sanger was born in the small village of Rendcomb, England. His father was a doctor. After having converted to quakerism he brought up his sons as quakers. Frederick Sanger studied and received his PhD at the University of Cambridge in 1943. He remained in Cambridge for the rest of his career. Frederick Sanger was married with three children.

Work

Proteins, which are molecules made up of chains of amino acids, play a pivotal role in life processes in our cells. One important protein is insulin, a hormone that regulates sugar content in blood. Beginning in the 1940s, Frederick Sanger studied the composition of the insulin molecule. He used acids to break the molecule into smaller parts, which were separated from one another with the help of electrophoresis and chromatography. Further analyses determined the amino acid sequences in the molecule’s two chains, and in 1955 Sanger identified how the chains are linked together.

Summary

Frederick Sanger (born August 13, 1918, Rendcombe, Gloucestershire, England—died November 19, 2013, Cambridge) was an English biochemist who was twice the recipient of the Nobel Prize for Chemistry. He was awarded the prize in 1958 for his determination of the structure of the insulin molecule. He shared the prize (with Paul Berg and Walter Gilbert) in 1980 for his determination of base sequences in nucleic acids. Sanger was the fourth two-time recipient of the Nobel Prize.

Education

Sanger was the middle child of Frederick Sanger, a medical practitioner, and Cicely Crewsdon Sanger, the daughter of a wealthy cotton manufacturer. The family expected him to follow in his father’s footsteps and become a medical doctor. After much thought, he decided to become a scientist. In 1936 Sanger entered St. John’s College, Cambridge. He initially concentrated on chemistry and physics, but he was later attracted to the new field of biochemistry. He received a bachelor’s degree in 1939 and stayed at Cambridge an additional year to take an advanced course in biochemistry. He and Joan Howe married in 1940 and subsequently had three children.

Because of his Quaker upbringing, Sanger was a conscientious objector and was assigned as an orderly to a hospital near Bristol when World War II began. He soon decided to visit Cambridge to see if he could enter the doctoral program in biochemistry. Several researchers there were interested in having a student, especially one who did not need money. He studied lysine metabolism with biochemist Albert Neuberger. They also had a project in support of the war effort, analyzing nitrogen from potatoes. Sanger received a doctorate in 1943.

Insulin research

Biochemist Albert C. Chibnall and his protein research group moved from Imperial College in London to the safer wartime environment of the biochemistry department at Cambridge. Two schools of thought existed among protein researchers at the time. One group thought proteins were complex mixtures that would not readily lend themselves to chemical analysis. Chibnall was in the other group, which considered a given protein to be a distinct chemical compound.

Chibnall was studying insulin when Sanger joined the group. At Chibnall’s suggestion, Sanger set out to identify and quantify the free-amino groups of insulin. Sanger developed a method using dinitrofluorobenzene to produce yellow-coloured derivatives of amino groups (see amino acid). Information about a new separation technique, partition chromatography, had recently been published. In a pattern that typified Sanger’s career, he immediately recognized the utility of the new technique in separating the hydrolysis products of the treated protein. He identified two terminal amino groups for insulin, phenylalanine and glycine, suggesting that insulin is composed of two types of chains. Working with his first graduate student, Rodney Porter, Sanger used the method to study the amino terminal groups of several other proteins. (Porter later shared the 1972 Nobel Prize for Physiology or Medicine for his work in determining the chemical structure of antibodies.)

On the assumption that insulin chains are held together by disulphide linkages, Sanger oxidized the chains and separated two fractions. One fraction had phenylalanine at its amino terminus; the other had glycine. Whereas complete acid hydrolysis degraded insulin to its constituent amino acids, partial acid hydrolysis generated insulin peptides composed of several amino acids. Using another recently introduced technique, paper chromatography, Sanger was able to sequence the amino-terminal peptides of each chain, demonstrating for the first time that a protein has a specific sequence at a specific site. A combination of partial acid hydrolysis and enzymatic hydrolysis allowed Sanger and the Austrian biochemist Hans Tuppy to determine the complete sequence of amino acids in the phenylalanine chain of insulin. Similarly, Sanger and the Australian biochemist E.O.P. Thompson determined the sequence of the glycine chain.

Two problems remained: the distribution of the amide groups and the location of the disulphide linkages. With the completion of those two puzzles in 1954, Sanger had deduced the structure of insulin. For being the first person to sequence a protein, Sanger was awarded the 1958 Nobel Prize for Chemistry.

Sanger and his coworkers continued their studies of insulin, sequencing insulin from several other species and comparing the results. Utilizing newly introduced radiolabeling techniques, Sanger mapped the amino acid sequences of the active centres from several enzymes. One of these studies was conducted with another graduate student, Argentine-born immunologist César Milstein. (Milstein later shared the 1984 Nobel Prize for Physiology or Medicine for discovering the principle for the production of monoclonal antibodies.)

RNA research

In 1962 the Medical Research Council opened its new laboratory of molecular biology in Cambridge. The Austrian-born British biochemist Max Perutz, British biochemist John Kendrew, and British biophysicist Francis Crick moved to the new laboratory. Sanger joined them as head of the protein division. It was a banner year for the group, as Perutz and Kendrew shared the 1962 Nobel Prize for Chemistry and Crick shared the 1962 Nobel Prize for Physiology or Medicine with the American geneticist James D. Watson and the New Zealand-born British biophysicist Maurice Wilkins for the discovery of DNA (deoxyribonucleic acid).

Sanger’s interaction with nucleic acid groups at the new laboratory led to his pursuing studies on ribonucleic acid (RNA). RNA molecules are much larger than proteins, so obtaining molecules small enough for technique development was difficult. The American biochemist Robert W. Holley and his coworkers were the first to sequence RNA when they sequenced alanine-transfer RNA. They used partial hydrolysis methods somewhat like those Sanger had used for insulin. Unlike other RNA types, transfer RNAs have many unusual nucleotides. This partial hydrolysis method would not work well with other RNA molecules, which contain only four types of nucleotides, so a new strategy was needed.

The goal of Sanger’s lab was to sequence a messenger RNA and determine the genetic code, thereby solving the puzzle of how groups of nucleotides code for amino acids. Working with British biochemists George G. Brownlee and Bart G. Barrell, Sanger developed a two-dimensional electrophoresis method for sequencing RNA. By the time the sequence methods were worked out, the code had been broken by other researchers, mainly the American biochemist Marshall Nirenberg and the Indian-born American biochemist Har Gobind Khorana, using in vitro protein synthesis techniques. The RNA sequence work of Sanger’s group did confirm the genetic code.

DNA research

By the early 1970s Sanger was interested in deoxyribonucleic acid (DNA). DNA sequence studies had not developed because of the immense size of DNA molecules and the lack of suitable enzymes to cleave DNA into smaller pieces. Building on the enzyme copying approach used by the Swiss chemist Charles Weissmann in his studies on bacteriophage RNA, Sanger began using the enzyme DNA polymerase to make new strands of DNA from single-strand templates, introducing radioactive nucleotides into the new DNA. DNA polymerase requires a primer that can bind to a known region of the template strand. Early success was limited by the lack of suitable primers. Sanger and British colleague Alan R. Coulson developed the “plus and minus” method for rapid DNA sequencing. It represented a radical departure from earlier methods in that it did not utilize partial hydrolysis. Instead, it generated a series of DNA molecules of varying lengths that could be separated by using polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis. For both plus and minus systems, DNA was synthesized from templates to generate random sets of DNA molecules from very short to very long. When both plus and minus sets were separated on the same gel, the sequence could be read from either system, one confirming the other. In 1977 Sanger’s group used this system to deduce most of the DNA sequence of bacteriophage ΦX174, the first complete genome to be sequenced.

A few problems remained with the plus and minus system. Sanger, Coulson, and British colleague Steve Nicklen developed a similar procedure using dideoxynucleotide chain-terminating inhibitors. DNA was synthesized until an inhibitor molecule was incorporated into the growing DNA chain. Using four reactions, each with a different inhibitor, sets of DNA fragments were generated ending in every nucleotide. For example, in the A reaction, a series of DNA fragments ending in A (adenine) was generated. In the C reaction, a series of DNA fragments ending in C (cytosine) was generated, and so on for G (guanine) and T (thymine). When the four reactions were separated side by side on a gel and an autoradiograph developed, the sequence was read from the film. Sanger and his coworkers used the dideoxy method to sequence human mitochondrial DNA. For his contributions to DNA sequencing methods, Sanger shared the 1980 Nobel Prize for Chemistry. He retired in 1983.

Additional Honors

Sanger’s additional honours included election as a fellow of the Royal Society (1954), being named a Commander of the Order of the British Empire (CBE; 1963), receiving the Royal Society’s Royal Medal (1969) and Copley Medal (1977), and election to the Order of the Companions of Honour (CH; 1981) and the Order of Merit (OM; 1986). In 1993 the Wellcome Trust and the British Medical Research Council established a genome research centre, honouring Sanger by naming it the Wellcome Trust Sanger Institute.

Details

Frederick Sanger (13 August 1918 – 19 November 2013) was a British biochemist who received the Nobel Prize in Chemistry twice.

He won the 1958 Chemistry Prize for determining the amino acid sequence of insulin and numerous other proteins, demonstrating in the process that each had a unique, definite structure; this was a foundational discovery for the central dogma of molecular biology.

At the newly constructed Laboratory of Molecular Biology in Cambridge, he developed and subsequently refined the first-ever DNA sequencing technique, which vastly expanded the number of feasible experiments in molecular biology and remains in widespread use today. The breakthrough earned him the 1980 Nobel Prize in Chemistry, which he shared with Walter Gilbert and Paul Berg.

He is one of only three people to have won multiple Nobel Prizes in the same category (the others being John Bardeen in physics and Karl Barry Sharpless in chemistry), and one of five persons with two Nobel Prizes.

Early life and education

Frederick Sanger was born on 13 August 1918 in Rendcomb, a small village in Gloucestershire, England, the second son of Frederick Sanger, a general practitioner, and his wife, Cicely Sanger (née Crewdson). He was one of three children. His brother, Theodore, was only a year older, while his sister May (Mary) was five years younger. His father had worked as an Anglican medical missionary in China but returned to England because of ill health. He was 40 in 1916 when he married Cicely, who was four years younger. Sanger's father converted to Quakerism soon after his two sons were born and brought up the children as Quakers. Sanger's mother was the daughter of an affluent cotton manufacturer and had a Quaker background, but was not a Quaker.

When Sanger was around five years old the family moved to the small village of Tanworth-in-Arden in Warwickshire. The family was reasonably wealthy and employed a governess to teach the children. In 1927, at the age of nine, he was sent to the Downs School, a residential preparatory school run by Quakers near Malvern. His brother Theo was a year ahead of him at the same school. In 1932, at the age of 14, he was sent to the recently established Bryanston School in Dorset. This used the Dalton system and had a more liberal regime which Sanger much preferred. At the school he liked his teachers and particularly enjoyed scientific subjects. Able to complete his School Certificate a year early, for which he was awarded seven credits, Sanger was able to spend most of his last year of school experimenting in the laboratory alongside his chemistry master, Geoffrey Ordish, who had originally studied at Cambridge University and been a researcher in the Cavendish Laboratory. Working with Ordish made a refreshing change from sitting and studying books and awakened Sanger's desire to pursue a scientific career. In 1935, prior to heading off to college, Sanger was sent to Schule Schloss Salem in southern Germany on an exchange program. The school placed a heavy emphasis on athletics, which caused Sanger to be much further ahead in the course material compared to the other students. He was shocked to learn that each day was started with readings from Hitler's Mein Kampf, followed by a Sieg Heil salute.

In 1936 Sanger went to St John's College, Cambridge, to study natural sciences. His father had attended the same college. For Part I of his Tripos he took courses in physics, chemistry, biochemistry and mathematics but struggled with physics and mathematics. Many of the other students had studied more mathematics at school. In his second year he replaced physics with physiology. He took three years to obtain his Part I. For his Part II he studied biochemistry and obtained a 1st Class Honours. Biochemistry was a relatively new department founded by Gowland Hopkins with enthusiastic lecturers who included Malcolm Dixon, Joseph Needham and Ernest Baldwin.

Both his parents died from cancer during his first two years at Cambridge. His father was 60 and his mother was 58. As an undergraduate Sanger's beliefs were strongly influenced by his Quaker upbringing. He was a pacifist and a member of the Peace Pledge Union. It was through his involvement with the Cambridge Scientists' Anti-War Group that he met his future wife, Joan Howe, who was studying economics at Newnham College. They courted while he was studying for his Part II exams and married after he had graduated in December 1940. Sanger, although brought up and influenced by his religious upbringing, later began to lose sight of his Quaker related ways. He began to see the world through a more scientific lens, and with the growth of his research and scientific development he slowly drifted farther from the faith he grew up with. He had nothing but respect for the religious and states he took two things from it, truth and respect for all life. Under the Military Training Act 1939 he was provisionally registered as a conscientious objector, and again under the National Service (Armed Forces) Act 1939, before being granted unconditional exemption from military service by a tribunal. In the meantime he undertook training in social relief work at the Quaker centre, Spicelands, Devon and served briefly as a hospital orderly.

Sanger began studying for a PhD in October 1940 under N.W. "Bill" Pirie. His project was to investigate whether edible protein could be obtained from grass. After little more than a month Pirie left the department and Albert Neuberger became his adviser. Sanger changed his research project to study the metabolism of lysine and a more practical problem concerning the nitrogen of potatoes. His thesis had the title, "The metabolism of the amino acid lysine in the animal body". He was examined by Charles Harington and Albert Charles Chibnall and awarded his doctorate in 1943.

#2 This is Cool » Integrated Circuit » Today 18:21:49

- Jai Ganesh

- Replies: 0

Integrated Circuit

Gist

An integrated circuit (IC), or microchip, is a tiny electronic device containing thousands to billions of interconnected transistors, resistors, and capacitors fabricated onto a single small piece of semiconductor material, usually silicon. This miniaturization allows for complex electronic functions, forming the backbone of modern electronics like smartphones, computers, and medical devices, replacing bulky, separate components.

The components are interconnected through a complex network of pathways etched onto the chip's surface. These pathways allow electrical signals to flow between the components, enabling the IC to perform specific functions, such as processing data, amplifying signals, or storing information.

Summary

An integrated circuit (IC), also known as a microchip or simply chip, is a compact assembly of electronic circuits formed from various electronic components — such as transistors, resistors, and capacitors — and their interconnections.[1] These components are fabricated onto a thin, flat piece ("chip") of semiconductor material, most commonly silicon. Integrated circuits are integral to a wide variety of electronic devices — including computers, smartphones, and televisions — performing functions such as data processing, control, and storage. They have transformed the field of electronics by enabling device miniaturization, improving performance, and reducing cost.

Compared to assemblies built from discrete components, integrated circuits are orders of magnitude smaller, faster, more energy-efficient, and less expensive, allowing for a very high transistor count. Its capability for mass production, its high reliability, and the standardized, modular approach of integrated circuit design facilitated rapid replacement of designs using discrete transistors. Today, ICs are present in virtually all electronic devices and have revolutionized modern technology. Products such as computer processors, microcontrollers, digital signal processors, and embedded processing chips in home appliances are foundational to contemporary society due to their small size, low cost, and versatility.

Very-large-scale integration was made practical by technological advancements in semiconductor device fabrication. Since their origins in the 1960s, the size, speed, and capacity of chips have progressed enormously, driven by technical advances that fit more and more transistors on chips of the same size – a modern chip may have many billions of transistors in an area the size of a human fingernail. These advances, roughly following Moore's law, make the computer chips of today possess millions of times the capacity and thousands of times the speed of the computer chips of the early 1970s.

ICs have three main advantages over circuits constructed out of discrete components: size, cost and performance. The size and cost is low because the chips, with all their components, are printed as a unit by photolithography rather than being constructed one transistor at a time. Furthermore, packaged ICs use much less material than discrete circuits. Performance is high because the IC's components switch quickly and consume comparatively little power because of their small size and proximity. The main disadvantage of ICs is the high initial cost of designing them and the enormous capital cost of factory construction. This high initial cost means ICs are only commercially viable when high production volumes are anticipated.

Details

An integrated circuit (IC) — commonly called a chip — is a compact, highly efficient semiconductor device that contains a multitude of interconnected electronic components such as transistors, resistors, and capacitors, all fabricated on a single piece of silicon. This revolutionary technology forms the backbone of modern electronics, enabling high-speed, miniaturized, and reliable devices found in everything from smartphones and computers to medical equipment and vehicles.

Before the invention of ICs, electronic systems relied on discrete components connected individually, resulting in bulky and unreliable systems. Integrated circuits enabled the miniaturization, increased performance, and cost-effectiveness that define today’s digital world.

What Do ICs Do?

You’re probably familiar with the little black boxes nestled neatly inside your favorite devices. With their diminutive size and unassuming characteristics, it can be hard to believe these vessels are actually the linchpin of most modern electronics. But without integrated chips, most technologies would not be possible, and we — as a technology-dependent society — would be helpless.

Integrated circuits are compact electronic chips made up of interconnected components that include resistors, transistors, and capacitors. Built on a single piece of semiconductor material, such as silicon, integrated circuits can contain collections of hundreds to billions of components — all working together to make our world go ‘round.

The uses of integrated circuits are vast: children’s toys, cars, computers, mobile phones, spaceships, subway trains, airplanes, video games, toothbrushes, and more. Basically, if it has a power switch, it likely owes its electronic life to an integrated circuit. An integrated circuit can function within each device as a microprocessor, amplifier, or memory.

Integrated circuits are created using photolithography, a process that uses ultraviolet light to print the components onto a single substrate all at once — similar to the way you can make many prints of a photograph from a single negative. The efficiency of printing all the IC’s components together means ICs can be produced more cheaply and reliably than using discrete components. Other benefits of ICs include:

* Extremely small size, so devices can be compact

* High reliability

* High-speed performance

* Low power requirement

Who Invented the Integrated Circuit?

The integrated circuit was independently invented by two pioneering engineers in the late 1950s: Jack Kilby of Texas Instruments and Robert Noyce of Fairchild Semiconductor.

Jack Kilby built the first working IC prototype in 1958 using germanium, which earned him the Nobel Prize in Physics in 2000 for his contribution to technology.

Robert Noyce developed a practical method for mass-producing ICs using silicon and the planar process, which laid the foundation for the modern semiconductor industry and led to the founding of Intel.

Their combined innovations set the stage for the explosive growth of electronics and computing power that continues today.

Evolution of IC Manufacturing

Since their creation, integrated circuits have gone through several evolutions to make our devices ever smaller, faster, and cheaper. While the first generation of ICs consisted of only a few components on a single chip, each generation since has prompted exponential leaps in power and economy.

1950s: Integrated circuits were introduced with only a few transistors and diodes on one chip.

1960s: The introduction of bipolar junction transistors and small- and medium-scale integration made it possible for thousands of transistors to be connected on a single chip.

1970s: Large-scale integration and very large-scale integration (VLSI) allowed for chips with tens of thousands, then millions of components, enabling the development of the personal computer and advanced computing systems.

2000s: In the early 2000s, ultra-large-scale integration (ULSI) allowed billions of components to be integrated on one substrate.

Next: The 2.5D and 3D integrated circuit (3D-IC) technologies currently under development will create unparalleled flexibility, propelling another great leap in electronics advancement.

The first IC manufacturers were vertically integrated companies that did all the design and manufacturing steps themselves. This is still the case for some companies like Intel, Samsung, and memory chip manufacturers. But since the 1980s, the “fabless” business model has become the norm in the semiconductor industry.

A fabless IC company does not manufacture the chips they design. Instead, they contract this out to dedicated manufacturing companies that operate fabrication facilities (fabs) shared by many design companies. Industry leaders like Apple, AMD, and NVIDIA are examples of fabless IC design houses. Leading IC manufacturers today include TSMC, Samsung, and GlobalFoundries.

What are the Main Types of Integrated Circuits?

ICs can be classified into different types based on their complexity and purpose. Some common types of ICs include:

* Digital ICs: These are used in devices such as computers and microprocessors. Digital ICs can be used for memory, storing data, or logic. They are economical and easy to design for low-frequency applications.

* Analog ICs: Analog ICs are designed to process continuous signals in which the signal magnitude varies from zero to full supply voltage. These ICs are used to process analog signals such as sound or light. In comparison to digital ICs, they are made of fewer transistors but are more difficult to design. Analog ICs can be used in a wide range of applications, including amplifiers, filters, oscillators, voltage regulators, and power management circuits. They are commonly found in electronic devices such as audio equipment, radio frequency (RF) transceivers, communications, sensors, and medical instruments.

* Mixed-signal ICs: Combining both digital and analog circuits, mixed-signal ICs are used in areas where both types of processing are required, such as screen, sensor, and communications applications in mobile phones, cars, and portable electronics.

* Memory ICs: These ICs are used store data both temporarily or permanently. Examples of memory ICs include random access memory (RAM) and read-only memory (ROM). Memory ICs are among the largest ICs in terms of transistor count and require extremely high-capacity and fast simulation tools.

* Application-Specific Integrated Circuit (ASIC): ASICs are designed to perform a particular task efficiently. It is not a general-purpose IC that can be implemented in most applications but is instead a system-on-chip (SoC) customized to execute a targeted function.

What is the Difference Between an IC and a Microprocessor?

While all microprocessors are integrated circuits, not all ICs are microprocessors. Here’s how they differ:

* Integrated Circuit (IC): A broad term for any chip that contains interconnected electronic components. ICs can be as simple as a single logic gate or as complex as a full system-on-chip (SoC).

* Microprocessor: A specific type of digital IC designed to function as the central processing unit (CPU) of a computer or embedded device. Microprocessors execute instructions, perform arithmetic and logic operations, and manage data flow.

In essence, a microprocessor is a highly specialized IC that acts as the “brain” of a computer, while ICs as a category include a wide range of chips with diverse functions.

Additional Information

An integrated circuit (IC) is an assembly of electronic components, fabricated as a single unit, in which miniaturized active devices (e.g., transistors and diodes) and passive devices (e.g., capacitors and resistors) and their interconnections are built up on a thin substrate of semiconductor material (typically silicon). The resulting circuit is thus a small monolithic “chip,” which may be as small as a few square centimetres or only a few square millimetres. The individual circuit components are generally microscopic in size.

Integrated circuits have their origin in the invention of the transistor in 1947 by William B. Shockley and his team at the American Telephone and Telegraph Company’s Bell Laboratories. Shockley’s team (including John Bardeen and Walter H. Brattain) found that, under the right circumstances, electrons would form a barrier at the surface of certain crystals, and they learned to control the flow of electricity through the crystal by manipulating this barrier. Controlling electron flow through a crystal allowed the team to create a device that could perform certain electrical operations, such as signal amplification, that were previously done by vacuum tubes. They named this device a transistor, from a combination of the words transfer and resistor. The study of methods of creating electronic devices using solid materials became known as solid-state electronics. Solid-state devices proved to be much sturdier, easier to work with, more reliable, much smaller, and less expensive than vacuum tubes. Using the same principles and materials, engineers soon learned to create other electrical components, such as resistors and capacitors. Now that electrical devices could be made so small, the largest part of a circuit was the awkward wiring between the devices.

In 1958 Jack Kilby of Texas Instruments, Inc., and Robert Noyce of Fairchild Semiconductor Corporation independently thought of a way to reduce circuit size further. They laid very thin paths of metal (usually aluminum or copper) directly on the same piece of material as their devices. These small paths acted as wires. With this technique an entire circuit could be “integrated” on a single piece of solid material and an integrated circuit (IC) thus created. ICs can contain hundreds of thousands of individual transistors on a single piece of material the size of a pea. Working with that many vacuum tubes would have been unrealistically awkward and expensive. The invention of the integrated circuit made technologies of the Information Age feasible. ICs are now used extensively in all walks of life, from cars to toasters to amusement park rides.

Basic IC types:

Analog versus digital circuits

Analog, or linear, circuits typically use only a few components and are thus some of the simplest types of ICs. Generally, analog circuits are connected to devices that collect signals from the environment or send signals back to the environment. For example, a microphone converts fluctuating vocal sounds into an electrical signal of varying voltage. An analog circuit then modifies the signal in some useful way—such as amplifying it or filtering it of undesirable noise. Such a signal might then be fed back to a loudspeaker, which would reproduce the tones originally picked up by the microphone. Another typical use for an analog circuit is to control some device in response to continual changes in the environment. For example, a temperature sensor sends a varying signal to a thermostat, which can be programmed to turn an air conditioner, heater, or oven on and off once the signal has reached a certain value.

A digital circuit, on the other hand, is designed to accept only voltages of specific given values. A circuit that uses only two states is known as a binary circuit. Circuit design with binary quantities, “on” and “off” representing 1 and 0 (i.e., true and false), uses the logic of Boolean algebra. (Arithmetic is also performed in the binary number system employing Boolean algebra.) These basic elements are combined in the design of ICs for digital computers and associated devices to perform the desired functions.

Microprocessor circuits

Microprocessors are the most-complicated ICs. They are composed of billions of transistors that have been configured as thousands of individual digital circuits, each of which performs some specific logic function. A microprocessor is built entirely of these logic circuits synchronized to each other. Microprocessors typically contain the central processing unit (CPU) of a computer.

Just like a marching band, the circuits perform their logic function only on direction by the bandmaster. The bandmaster in a microprocessor, so to speak, is called the clock. The clock is a signal that quickly alternates between two logic states. Every time the clock changes state, every logic circuit in the microprocessor does something. Calculations can be made very quickly, depending on the speed (clock frequency) of the microprocessor.

Microprocessors contain some circuits, known as registers, that store information. Registers are predetermined memory locations. Each processor has many different types of registers. Permanent registers are used to store the preprogrammed instructions required for various operations (such as addition and multiplication). Temporary registers store numbers that are to be operated on and also the result. Other examples of registers include the program counter (also called the instruction pointer), which contains the address in memory of the next instruction; the stack pointer (also called the stack register), which contains the address of the last instruction put into an area of memory called the stack; and the memory address register, which contains the address of where the data to be worked on is located or where the data that has been processed will be stored.

Microprocessors can perform billions of operations per second on data. In addition to computers, microprocessors are common in video game systems, televisions, cameras, and automobiles.

Memory circuits

Microprocessors typically have to store more data than can be held in a few registers. This additional information is relocated to special memory circuits. Memory is composed of dense arrays of parallel circuits that use their voltage states to store information. Memory also stores the temporary sequence of instructions, or program, for the microprocessor.

Manufacturers continually strive to reduce the size of memory circuits—to increase capability without increasing space. In addition, smaller components typically use less power, operate more efficiently, and cost less to manufacture.

Digital signal processors

A signal is an analog waveform—anything in the environment that can be captured electronically. A digital signal is an analog waveform that has been converted into a series of binary numbers for quick manipulation. As the name implies, a digital signal processor (DSP) processes signals digitally, as patterns of 1s and 0s. For instance, using an analog-to-digital converter, commonly called an A-to-D or A/D converter, a recording of someone’s voice can be converted into digital 1s and 0s. The digital representation of the voice can then be modified by a DSP using complex mathematical formulas. For example, the DSP algorithm in the circuit may be configured to recognize gaps between spoken words as background noise and digitally remove ambient noise from the waveform. Finally, the processed signal can be converted back (by a D/A converter) into an analog signal for listening. Digital processing can filter out background noise so fast that there is no discernible delay and the signal appears to be heard in “real time.” For instance, such processing enables “live” television broadcasts to focus on a quarterback’s signals in an American gridiron football game.

DSPs are also used to produce digital effects on live television. For example, the yellow marker lines displayed during the football game are not really on the field; a DSP adds the lines after the cameras shoot the picture but before it is broadcast. Similarly, some of the advertisements seen on stadium fences and billboards during televised sporting events are not really there.

Application-specific ICs

An application-specific IC (ASIC) can be either a digital or an analog circuit. As their name implies, ASICs are not reconfigurable; they perform only one specific function. For example, a speed controller IC for a remote control car is hard-wired to do one job and could never become a microprocessor. An ASIC does not contain any ability to follow alternate instructions.

Radio-frequency ICs

Radio-frequency ICs (RFICs) are widely used in mobile phones and wireless devices. RFICs are analog circuits that usually run in the frequency range of 3 kHz to 2.4 GHz (3,000 hertz to 2.4 billion hertz), circuits that would work at about 1 THz (1 trillion hertz) being in development. They are usually thought of as ASICs even though some may be configurable for several similar applications.

Most semiconductor circuits that operate above 500 MHz (500 million hertz) cause the electronic components and their connecting paths to interfere with each other in unusual ways. Engineers must use special design techniques to deal with the physics of high-frequency microelectronic interactions.

Monolithic microwave ICs

A special type of RFIC is known as a monolithic microwave IC (MMIC; also called microwave monolithic IC). These circuits usually run in the 2- to 100-GHz range, or microwave frequencies, and are used in radar systems, in satellite communications, and as power amplifiers for cellular telephones.

Just as sound travels faster through water than through air, electron velocity is different through each type of semiconductor material. Silicon offers too much resistance for microwave-frequency circuits, and so the compound GaAs is often used for MMICs. Unfortunately, GaAs is mechanically much less sound than silicon. It breaks easily, so GaAs wafers are usually much more expensive to build than silicon wafers.

#3 Re: This is Cool » Miscellany » Today 17:48:23

2491) Red Sea

Gist

The Red Sea is a vital 2,250 km long, 355 km wide, and up to 2,730 m deep, narrow, and hypersaline inlet of the Indian Ocean, positioned between Northeast Africa and the Arabian Peninsula. As a crucial, warm-water maritime trade route (carrying 12%) of global trade) connected via the Suez Canal and Bab-el-Mandeb Strait, it separates countries like Egypt, Sudan, and Eritrea from Saudi Arabia and Yemen.

The Red Sea is known for its vital trade route (Suez Canal), incredibly rich biodiversity with vibrant coral reefs and unique marine life, extremely warm and salty water, year-round sunshine, and significant historical/religious importance, particularly the biblical story of Moses. It's a major global hotspot for scuba diving and snorkeling due to its clear waters and abundant fish species.

Summary

The Red Sea is a sea inlet of the Indian Ocean, lying between Africa and Asia. Its connection to the ocean is in the south, through the Bab-el-Mandeb Strait and the Gulf of Aden. To the north of the Red Sea lies the Sinai Peninsula, the Gulf of Aqaba, and the Gulf of Suez, which leads to the Suez Canal. It is underlain by the Red Sea Rift, which is part of the Great Rift Valley.

The Red Sea has a surface area of roughly 438,000 sq km (169,000 sq mi), is about 2,250 km (1,400 mi) long, and 355 km (221 mi) across at its widest point. It has an average depth of 490 m (1,610 ft), and in the central Suakin Trough, it reaches its maximum depth of 2,730 m (8,960 ft).

The Red Sea is quite shallow, with approximately 40% of its area being less than 100 m (330 ft) deep, and approximately 25% being less than 50 m (160 ft) deep. The extensive shallow shelves are noted for their marine life and corals. More than 1,000 invertebrate species and 200 types of soft and hard coral live in the sea. The Red Sea is the world's northernmost tropical sea and has been designated a Global 200 ecoregion.

Details

Red Sea is a narrow strip of water extending southeastward from Suez, Egypt, for about 1,200 miles (1,930 km) to the Bab el-Mandeb Strait, which connects with the Gulf of Aden and thence with the Arabian Sea. Geologically, the Gulfs of Suez and Aqaba (Elat) must be considered as the northern extension of the same structure. The sea separates the coasts of Egypt, Sudan, and Eritrea to the west from those of Saudi Arabia and Yemen to the east. Its maximum width is 190 miles, its greatest depth 9,974 feet (3,040 metres), and its area approximately 174,000 square miles (450,000 square km).

The Red Sea contains some of the world’s hottest and saltiest seawater. With its connection to the Mediterranean Sea via the Suez Canal, it is one of the most heavily traveled waterways in the world, carrying maritime traffic between Europe and Asia. Its name is derived from the colour changes observed in its waters. Normally, the Red Sea is an intense blue-green; occasionally, however, it is populated by extensive blooms of the algae Trichodesmium erythraeum, which, upon dying off, turn the sea a reddish brown colour.

The following discussion focuses on the Red Sea and the Gulfs of Suez and Aqaba.

Physical features:

Physiography and submarine morphology

The Red Sea lies in a fault depression that separates two great blocks of Earth’s crust—Arabia and North Africa. The land on either side, inland from the coastal plains, reaches heights of more than 6,560 feet above sea level, with the highest land in the south.

At its northern end the Red Sea splits into two parts, the Gulf of Suez to the northwest and the Gulf of Aqaba to the northeast. The Gulf of Suez is shallow—approximately 180 to 210 feet deep—and it is bordered by a broad coastal plain. The Gulf of Aqaba, on the other hand, is bordered by a narrow plain, and it reaches a depth of 5,500 feet. From approximately 28° N, where the Gulfs of Suez and Aqaba converge, south to a latitude near 25° N, the Red Sea’s coasts parallel each other at a distance of roughly 100 miles apart. There the seafloor consists of a main trough, with a maximum depth of some 4,000 feet, running parallel to the shorelines.

South of this point and continuing southeast to latitude 16° N, the main trough becomes sinuous, following the irregularities of the shoreline. About halfway down this section, roughly between 20° and 21° N, the topography of the trough becomes more rugged, and several sharp clefts appear in the seafloor. Because of an extensive growth of coral banks, only a shallow narrow channel remains south of 16° N. The sill (submarine ridge) separating the Red Sea and the Gulf of Aden at the Bab el-Mandeb Strait is affected by this growth; therefore, the depth of the water is only about 380 feet, and the main channel becomes narrow.

The clefts within the deeper part of the trough are unusual seafloor areas in which hot brine concentrates are found. These patches apparently form distinct and separated deeps within the trough and have a north-south trend, whereas the general trend of the trough is from northwest to southeast. At the bottom of these areas are unique sediments, containing deposits of heavy metal oxides from 30 to 60 feet thick.

Most of the islands of the Red Sea are merely exposed reefs. There is, however, a group of active volcanoes just south of the Dahlak Archipelago (15° 50′ N), as well as a recently extinct volcano on the island of Jabal Al-Ṭāʾir.

Geology

The Red Sea occupies part of a large rift valley in the continental crust of Africa and Arabia. This break in the crust is part of a complex rift system that includes the East African Rift System, which extends southward through Ethiopia, Kenya, and Tanzania for almost 2,200 miles and northward for more than 280 miles from the Gulf of Aqaba to form the great Wadi Aqaba–Dead Sea–Jordan Rift; the system also extends eastward for 600 miles from the southern end of the Red Sea to form the Gulf of Aden.

The Red Sea valley cuts through the Arabian-Nubian Massif, which was a continuous central mass of Precambrian igneous and metamorphic rocks (i.e., formed deep within the Earth under heat and pressure more than 540 million years ago), the outcrops of which form the rugged mountains of the adjoining region. The massif is surrounded by these Precambrian rocks overlain by Paleozoic marine sediments (542 to 251 million years old). These sediments were affected by the folding and faulting that began late in the Paleozoic; the laying down of deposits, however, continued to occur during this time and apparently continued into the Mesozoic Era (251 to 65.5 million years ago). The Mesozoic sediments appear to surround and overlap those of the Paleozoic and are in turn surrounded by early Cenozoic sediments (i.e., between 65.5 and 55.8 million years old). In many places large remnants of Mesozoic sediments are found overlying the Precambrian rocks, suggesting that a fairly continuous cover of deposits once existed above the older massif.

The Red Sea is considered a relatively new sea, whose development probably resembles that of the Atlantic Ocean in its early stages. The Red Sea’s trough apparently formed in at least two complex phases of land motion. The movement of Africa away from Arabia began about 55 million years ago. The Gulf of Suez opened up about 30 million years ago, and the northern part of the Red Sea about 20 million years ago. The second phase began about 3 to 4 million years ago, creating the trough in the Gulf of Aqaba and also in the southern half of the Red Sea valley. This motion, estimated as amounting to 0.59 to 0.62 inch (15.0 to 15.7 mm) per year, is still proceeding, as indicated by the extensive volcanism of the past 10,000 years, by seismic activity, and by the flow of hot brines in the trough.

Climate

The Red Sea region receives very little precipitation in any form, although prehistoric artifacts indicate that there were periods with greater amounts of rainfall. In general, the climate is conducive to outdoor activity in fall, winter, and spring—except during windstorms—with temperatures varying between 46 and 82 °F (8 and 28 °C). Summer temperatures, however, are much higher, up to 104 °F (40 °C), and relative humidity is high, rendering vigorous activity unpleasant. In the northern part of the Red Sea area, extending down to 19° N, the prevailing winds are north to northwest. Best known are the occasional westerly, or “Egyptian,” winds, which blow with some violence during the winter months and generally are accompanied by fog and blowing sand. From latitude 14° to 16° N the winds are variable, but from June through August strong northwest winds move down from the north, sometimes extending as far south as the Bab el-Mandeb Strait; by September, however, this wind pattern retreats to a position north of 16° N. South of 14° N the prevailing winds are south to southeast.

Hydrology

No water enters the Red Sea from rivers, and rainfall is scant; but the evaporation loss—in excess of 80 inches per year—is made up by an inflow through the eastern channel of the Bab el-Mandeb Strait from the Gulf of Aden. This inflow is driven toward the north by prevailing winds and generates a circulation pattern in which these low-salinity waters (the average salinity is about 36 parts per thousand) move northward. Water from the Gulf of Suez has a salinity of about 40 parts per thousand, owing in part to evaporation, and consequently a high density. This dense water moves toward the south and sinks below the less dense inflowing waters from the Red Sea. Below a transition zone, which extends from depths of about 300 to 1,300 feet, the water conditions are stabilized at about 72 °F (22 °C), with a salinity of almost 41 parts per thousand. This south-flowing bottom water, displaced from the north, spills over the sill at Bab el-Mandeb, mostly through the eastern channel. It is estimated that there is a complete renewal of water in the Red Sea every 20 years.

Below this southward-flowing water, in the deepest portions of the trough, there is another transition layer, only 80 feet thick, below which, at some 6,400 feet, lie pools of hot brine. The brine in the Atlantis II Deep has an average temperature of almost 140 °F (60 °C), a salinity of 257 parts per thousand, and no oxygen. There are similar pools of water in the Discovery Deep and in the Chain Deep (at about 21°18′ N). Heating from below renders these pools unstable, so that their contents mix with the overlying waters; they thus become part of the general circulation system of the sea.

Economic aspects:

Resources

Five major types of mineral resources are found in the Red Sea region: petroleum deposits, evaporite deposits (sediments laid down as a result of evaporation, such as halite, sylvite, gypsum, and dolomite), sulfur, phosphates, and the heavy-metal deposits in the bottom oozes of the Atlantis II, Discovery, and other deeps. The oil and natural gas deposits have been exploited to varying degrees by the nations adjoining the sea; of note are the deposits near Jamsah (Gemsa) Promontory (in Egypt) at the juncture of the Gulf of Suez and the Red Sea. Despite their ready availability, the evaporites have been exploited only slightly, primarily on a local basis. Sulfur has been mined extensively since the early 20th century, particularly from deposits at Jamsah Promontory. Phosphate deposits are present on both sides of the sea, but the grade of the ore has been too low to warrant exploitation with existing techniques.

None of the heavy metal deposits have been exploited, although the sediments of the Atlantis II Deep alone have been estimated to be of considerable economic value. The average analysis of the Atlantis II Deep deposit has revealed an iron content of 29 percent; zinc 3.4 percent; copper 1.3 percent; and trace quantities of lead, silver, and gold. The total brine-free sediment estimated to be present in the upper 30 feet of the Atlantis II Deep is about 50 million tons. These deposits appear to extend to a depth of 60 feet below the present sediment surface, but the quality of the deposits below 30 feet is unknown. The sediments of the Discovery Deep and of several other deposits also have significant metalliferous content but at lower concentrations than that in the Atlantis II Deep, and thus they have not been of as much economic interest. The recovery of sediment located beneath 5,700 to 6,400 feet of water poses problems. But since most of these metalliferous deposits are fluid oozes, it is thought to be possible to pump them to the surface in much the same way as oil. There also are numerous proposals for drying and beneficiating (treating for smelting) these deposits after recovery.

Navigation

Navigation in the Red Sea is difficult. The unindented shorelines of the sea’s northern half provide few natural harbours, and in the southern half the growth of coral reefs has restricted the navigable channel and blocked some harbour facilities. At Bab el-Mandeb Strait, the channel is kept open to shipping by blasting and dredging. Atmospheric distortion (heat shimmer), sandstorms, and highly irregular water currents add to the navigational hazards.

Study and exploration

The Red Sea is one of the first large bodies of water mentioned in recorded history. It was important in early Egyptian maritime commerce (2000 bce) and was used as a water route to India by about 1000 bce. It is believed that it was reasonably well-charted by 1500 bce, because at that time Queen Hatshepsut of Egypt sailed its length. Later the Phoenicians explored its shores during their circumnavigatory exploration of Africa in about 600 bce. Shallow canals were dug between the Nile and the Red Sea before the 1st century ce but were later abandoned. A deep canal between the Mediterranean and Red seas was first suggested about 800 ce by the caliph Hārūn al-Rashīd, but it was not until 1869 that the French diplomat Ferdinand de Lesseps oversaw the completion of the Suez Canal connecting the two seas.

The Red Sea was subject to substantial scientific research in the 20th century, particularly since World War II. Notable cruises included those of the Swedish research vessel Albatross (1948) and the American Glomar Challenger (1972). In addition to studying the sea’s chemical and biological properties, researchers focused considerable attention on understanding its geologic structure. Much of the geologic study was in conjunction with oil exploration.

Additional Information

When my friends and family ask me what I am doing in my research, I respond that “I am investigating the winds and currents of the Red Sea in the Middle East.” Scary faces pop up. All they see are the winds of wars—the ever-present terrorist attacks, fighting, and killings in the region. “Are you crazy?” they say.

I get this same question (and sometimes the same reaction) from my oceanography colleagues. Since I began my postdoctoral research at Woods Hole Oceanographic Institution, working with WHOI physical oceanographers Amy Bower and Tom Farrar, I have learned two things: first, that few people realize how beautiful the Middle East is, and second, that the seas there have fascinating and unusual characteristics and far-reaching impacts on life in and around them. These seas furnish moisture for the arid Middle Eastern atmosphere and allowed great civilizations to flourish thousands of years ago around these seas.

For an oceanographer like myself, the Red Sea can be viewed as a mini-ocean, like a toy model ocean. Most of the oceanic features in a big ocean such as the Atlantic, we can also find there.

But the Red Sea also has its own curious characteristics that are not seen in other oceans. It is extremely warm—temperatures in its surface waters reach than 30° Celsius (86° Fahrenheit)—and water evaporates from it at a prodigious rate, making it extremely salty. Because of its narrow confines and constricted connection to the global ocean and because it is subject to seasonal flip-flopping wind patterns governed by the monsoons, it has odd circulation patterns. Its currents change in summer and winter.

The Red Sea is one of the few places on Earth that has what is known as a poleward-flowing eastern boundary current. Eastern boundary currents are so called because they hug the eastern coasts of continents. But all other such eastern boundary currents head south in the northern hemisphere. But the Red Sea Eastern Boundary Current, unlike all others, flows in the direction of the North Pole.

Unravelling the intricate tapestry that creates this rare eastern boundary current in the Red Sea was a goal of my postdoctoral research. But I have found that the Red Sea is far more mesmerizing and complex than I initially imagined. A variety of exotic threads are woven into the tapestry that produce the Red Sea’s unusual oceanographic phenomena: seasonal monsoons, desert sandstorms, wind jets through narrow mountain gaps, the Strait of Bab Al Mandeb that squeezes passage in and out of the sea—even locust swarms.

The politics of the nations surrounding the Red Sea are also complex and make it among the more difficult places to collect data. That explains why many Red Sea phenomena have remained unknown. But unexplored regions are the juiciest for scientists, because they are the ripest places to make new discoveries.

Gateway to the Red Sea

In the Red Sea, the water evaporates at one of the highest rates in the world. Like a bathtub in a steam room, you would have to add water from the tap to keep its water level stable.

The Red Sea compensates for the large water volume it loses each year through evaporation by importing water from the Gulf of Aden—through the narrow Strait of Bab Al Mandeb between Yemen on the Arabian Peninsula and Djibouti and Eritrea on the Horn of Africa.

The Strait of Bab Al Mandeb works as a gate. All waters in and out of the sea must pass through it. No other gates exist, making the Red Sea what is known as a semi-enclosed marginal sea.

In winter, incoming surface waters from the Gulf of Aden flow in a typical western boundary current, hugging the western side of the Red Sea along the coasts of Eritrea and Sudan. The current transports the waters northward. But in the central part of the Red Sea, this current veers sharply to the right. When it reaches the eastern side, it continues its convoluted journey to the north, but now it hugs the eastern side of the sea along coast of Saudi Arabia.

Here’s where the mystery deepens. The Red Sea Eastern Boundary Current exists only in winter. In summer, it’s not there. I wanted to find out how it forms, how it changes, and why it seasonally disappears.

Detectives and pirates

To unravel the complex tapestry that makes the Red Sea Eastern Boundary Current, I am like a CSI (Crime Scene Investigator) agent, sifting through as much data as I can get and putting them together to solve a mystery.

But it’s hard to obtain data from the Red Sea. Its narrow confines mean that its waters are restricted by countries around it that are often in conflict. It’s hard for researchers to get permission to enter them.

In addition, many waters in and enroute to the Red Sea have been beset by piracy. In the spring of 2018, I was aboard of the NOAA ship Ronald H. Brown in the Arabian Sea. It was the first time in more than a decade that the U.S. Navy allowed an American research vessel to go to the Arabian Sea. We were allowed to go only on the eastern side, and we couldn’t go anywhere beyond 17.5° N, because it wasn’t safe. On board, we conducted many safety drills, learning how to hide from pirates.

The Red Sea is also hard for satellites. Its width is small compared with the spatial resolution of most oceanographic satellites. Altimeter and wind satellites have a spatial resolution around 30 to 50 kilometers. The maximum Red Sea width is only 355 kilometers. In addition, satellites can give us information about what happens at the sea surface, but they can’t reveal the mixing and other processes that go on beneath the surface.

That’s why my research was kidnapped and carried off into an unanticipated direction, and my focus shifted from sea to air.

A plague of locusts

In the Red Sea, evaporation is a critical factor driving how the sea operates, and to determine how much water evaporates, we need to know about the winds. Why? Because evaporation rates depend on the winds. If the winds are stronger, the evaporation is stronger; if the winds are weaker, evaporation is weaker.

To complicate the situation a bit more, evaporation depends not only on the strength of the winds but where the winds are coming from. If the winds are coming over the sea, the air humidity in the winds will be higher, and evaporation will be lower; if the winds are coming from the desert, the air will be dry, and evaporation will be higher.

So, to unravel the Eastern Boundary Current, we needed to have a pretty good picture of how the winds blow in winter. When I started my postdoctoral research, I was really surprised to see that this important factor—the wind variability of the Red Sea—wasn’t well-known, even though interest on it goes way back!

Pioneering studies about winds in the Red Sea were motivated by a desire to determine the northward migration of desert locust swarms that invade areas and voraciously consume all the vegetation in it. This plague has been described in the Old Testament of the Bible and has tormented countries bordering the Red Sea since times immemorial.

The locusts breed along the shores of the Red Sea. Summer monsoon rains spur locust eggs to hatch. When enough rains fall to create plenty of water and vegetation for food, large numbers of locusts hatch and form swarms. Winds determine where the swarms will be carried off to infest neighboring regions.

Lining both sides of the Red Sea are tall mountains that create a kind of tunnel, so that winds blow predominantly along, not across, the Red Sea. In summer, the winds blow from north to south. In winter, however, the monsoon flips the wind direction in the southern part of the Red Sea, andtwo opposing airstreams meet at some point in the central Red Sea called the Red Sea Convergence Zone. It acts as a conduit for migrating locust swarms, and where it is positioned determines where the swarms go.

Mountain-gap wind jets

The mountains along Red Sea coasts affect the winds in another way. The mountains aren’t entirely compact; there are several gaps in them. The tunnel surrounding the Red Sea has a few holes in both sides. Sometimes the winds blow through one of these holes and cross the tunnel. These are the mountain-gap wind jets.

The mountain-gap winds in summer blow from Africa to Saudi Arabia through the Tokar Gap near the Sudanese coast. In winter, the mountain-gap winds blow in the opposite direction, from Saudi Arabia to Africa, through many nameless gaps in the northern part of the Red Sea.

These jets stir up frequent sandstorms carrying sand and dirt from surrounding deserts into the Red Sea. The sandstorms carry fertilizing nutrients that promote life in the Red Sea. The sands also block incoming sunlight and cool the sea surface.

But do these overlooked jets also affect the Red Sea in other ways?

Blasts of dry air

We decided to put together lots of different data to find out the fundamental characteristics of these mountain-gap jet events. Our data came from satellites and from a heavily instrumented mooring that measured winds and humidity in the air and temperatures and salinity in the sea below. WHOI maintained the mooring for two-years in the Red Sea when it collaborated with King Abdullah University of Science and Technology.

The satellite images revealed that these events weren’t rare. We learned that in most winters, there are typically two to three events in December and January in which the winds blow west across the northern part of the Red Sea. In satellite images, they are impressive and beautiful.

The mountain-gap events typically last three to eight days. We observed large year-to-year differences, with an increasing number of events in the last decade.

We discovered that the wintertime mountain-gap wind events blast the Red Sea with dry air. They are like the cold-air outbreaks that hit the U.S. East Coast in winter. Of course, for the Red Sea, it would be better to name them as dry-air outbreaks!

The dry-air blasts abruptly increase evaporation on the surface of the sea. This colossal evaporation removes a large amount of heat and water vapor out of the sea, leaving it much saltier. The mountain-gap winds also stir up deeper, cooler waters that mix with surface waters.

The waters become saltier and colder. This disrupts the Eastern Boundary Current. During most wind-jet events, it seems to fade away.

Connecting the oceans

We are still looking for answers about how the Eastern Boundary Current forms and why it flows north. But we have learned much about the wind-jet events that cause it to disappear periodically in winter.

The large-scale evaporation from these wind-jet events may also drive waters in the northern Red Sea to become cooler, saltier, and dense enough to sink the depths and flow all the way south and back out of the Strait of Bab Al Mandeb.

These salty Red Sea waters escape to the Gulf Aden, where they start a long journey through the Indian Ocean. They cross the Equator. Some may travel into the Atlantic Ocean. Some may flow toward Western Australia.

#4 Dark Discussions at Cafe Infinity » Combined Quotes - II » Today 17:05:58

- Jai Ganesh

- Replies: 0

Combined Quotes - II

1. The human animal cannot be trusted for anything good except en masse. The combined thought and action of the whole people of any race, creed or nationality, will always point in the right direction. - Harry S Truman

2. I'll try to work on being an all-rounder and if something doesn't work out then my batting is always there. But Hardik Pandya combined with both bat and ball, it sounds better than just a batter. - Hardik Pandya

3. Maybe we can see more men's and women's combined events so the young players can be marketed better. - Mats Wilander

4. I have relationships with people I'm working with, based on our combined interest. It doesn't make the relationship any less sincere, but it does give it a focus that may not last beyond the experience. - Harrison Ford

5. My parent's divorce and hard times at school, all those things combined to mold me, to make me grow up quicker. And it gave me the drive to pursue my dreams that I wouldn't necessarily have had otherwise. - Christina Aguilera

6. There isn't a flaw in his golf or his makeup. He will win more majors than Arnold Palmer and me combined. Somebody is going to dust my records. It might as well be Tiger, because he's such a great kid. - Jack Nicklaus

7. You know you're not anonymous on our site. We're greeting you by name, showing you past purchases, to the degree that you can arrange to have transparency combined with an explanation of what the consumer benefit is. - Jeff Bezos

8. Intelligence and courtesy not always are combined; Often in a wooden house a golden room we find. - Henry Wadsworth Longfellow.

#5 Jokes » Corn Jokes - II » Today 16:43:57

- Jai Ganesh

- Replies: 0

Q: Why shouldn't you tell a secret on a farm?

A: Because the potatoes have eyes, the corn has ears, and the beans stalk.

* * *

Q: How is an ear of corn like an army?

A: It has lots of kernels.

* * *

Q: What do you call the State fair in Iowa?

A: A corn-ival.

* * *

Q: What do you call a buccaneer?

A: A good price for corn.

* * *

Q: What do you get when a Corn cob is runover by a truck?

A: "Creamed" corn.

* * *

#6 Science HQ » Wavelength » Today 16:37:22

- Jai Ganesh

- Replies: 0

Wavelength

Gist

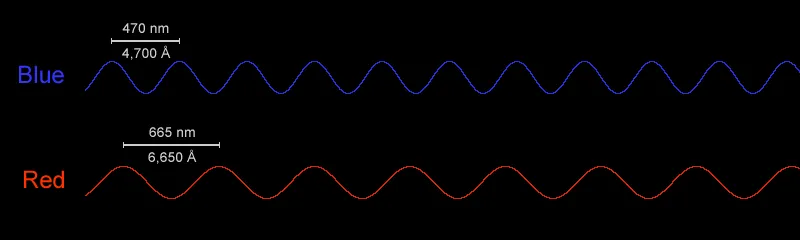

Wavelength is the spatial distance over which a wave's shape repeats, measured from one peak to the next (or trough to trough), represented by the Greek letter lambda. It's a fundamental property of waves (like light, sound, water) and is inversely related to frequency (higher frequency means shorter wavelength, like blue light). In common language, being "on the same wavelength" means sharing understanding, while in technology, AWS Wavelength provides edge computing for low-latency applications.

Wavelength is the distance between two corresponding points on consecutive waves, like from one crest to the next or one trough to the next, representing the spatial period of a wave. Denoted by the Greek letter lambda, it's a fundamental property of waves (light, sound, etc.) and is inversely proportional to frequency; longer wavelengths have lower frequencies, and shorter wavelengths have higher frequencies, measured in meters (m) or nanometers (nm).

Summary

Wavelength is the distance between corresponding points of two consecutive waves. “Corresponding points” refers to two points or particles in the same phase—i.e., points that have completed identical fractions of their periodic motion. Usually, in transverse waves (waves with points oscillating at right angles to the direction of their advance), wavelength is measured from crest to crest or from trough to trough; in longitudinal waves (waves with points vibrating in the same direction as their advance), it is measured from compression to compression or from rarefaction to rarefaction. Wavelength is usually denoted by the Greek letter lambda (λ); it is equal to the speed (v) of a wave train in a medium divided by its frequency (f): λ = v/f.

Details

In physics and mathematics, wavelength or spatial period of a wave or periodic function is the distance over which the wave's shape repeats. In other words, it is the distance between consecutive corresponding points of the same phase on the wave, such as two adjacent crests, troughs, or zero crossings. Wavelength is a characteristic of both traveling waves and standing waves, as well as other spatial wave patterns. The inverse of the wavelength is called the spatial frequency. Wavelength is commonly designated by the Greek letter lambda (λ). For a modulated wave, wavelength may refer to the carrier wavelength of the signal. The term wavelength may also apply to the repeating envelope of modulated waves or waves formed by interference of several sinusoids.

Assuming a sinusoidal wave moving at a fixed wave speed, wavelength is inversely proportional to the frequency of the wave: waves with higher frequencies have shorter wavelengths, and lower frequencies have longer wavelengths.

Wavelength depends on the medium (for example, vacuum, air, or water) that a wave travels through. Examples of waves are sound waves, light, water waves, and periodic electrical signals in a conductor. A sound wave is a variation in air pressure, while in light and other electromagnetic radiation the strength of the electric and the magnetic field vary. Water waves are variations in the height of a body of water. In a crystal lattice vibration, atomic positions vary.

The range of wavelengths or frequencies for wave phenomena is called a spectrum. The name originated with the visible light spectrum but now can be applied to the entire electromagnetic spectrum as well as to a sound spectrum or vibration spectrum.

Additional Information

There are many kinds of waves all around us. There are waves in the ocean and in lakes. Did you also know that there are also waves in the air? Sound travels through the air in waves and light is made up of waves of electromagnetic energy.

The wavelength of a wave describes how long the wave is. The distance from the "crest" (top) of one wave to the crest of the next wave is the wavelength. Alternately, we can measure from the "trough" (bottom) of one wave to the trough of the next wave and get the same value for the wavelength.

The frequency of a wave is inversely proportional to its wavelength. That means that waves with a high frequency have a short wavelength, while waves with a low frequency have a longer wavelength.

Light waves have very, very short wavelengths. Red light waves have wavelengths around 700 nanometers (nm), while blue and purple light have even shorter waves with wavelengths around 400 or 500 nm. Some radio waves, another type of electromagnetic radiation, have much longer waves than light, with wavelengths ranging from millimeters to kilometers.

Sound waves traveling through air have wavelengths from millimeters to meters. Low-pitch bass notes that humans can barely hear have huge wavelengths around 17 meters and frequencies around 20 hertz (Hz). Extremely high-pitched sounds that are on the other edge of the range that humans can hear have smaller wavelengths around 17 mm and frequencies around 20 kHz (kilohertz, or thousands of Hertz).

#7 Re: Jai Ganesh's Puzzles » General Quiz » Today 15:58:51

Hi,

#10739. What does the term in Biology Food chain mean?

#10740. What does the term in Biology Foramen mean?

#8 Re: Jai Ganesh's Puzzles » English language puzzles » Today 15:42:13

Hi,

#5935. What does the adjective freehand mean?

#5936. What does the noun freehold mean?

#9 Re: Jai Ganesh's Puzzles » Doc, Doc! » Today 15:30:37

Hi,

#2564. What does the medical term Dix–Hallpike test mean?

#10 Re: Jai Ganesh's Puzzles » 10 second questions » Today 14:58:17

Hi,

#9849.

#11 Re: Jai Ganesh's Puzzles » Oral puzzles » Today 14:46:18

Hi,

#6343.

#12 Re: Exercises » Compute the solution: » Today 14:32:00

Hi,

2700.

#13 This is Cool » Transistor » Yesterday 18:28:38

- Jai Ganesh

- Replies: 0

Transistor

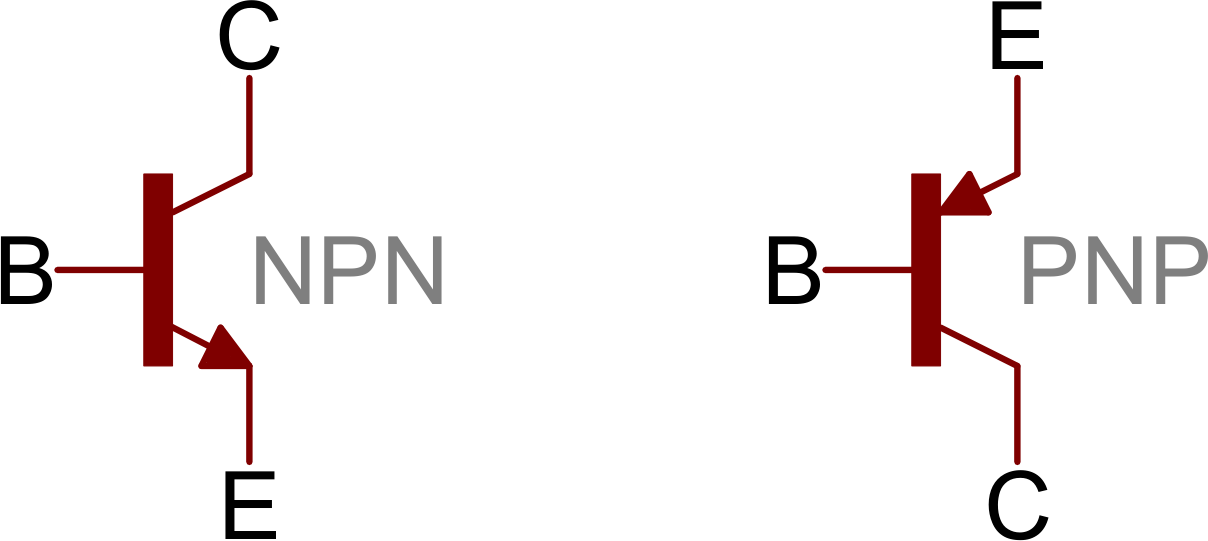

Gist

A transistor is a semiconductor device that amplifies or switches electronic signals and power, acting as a fundamental building block of modern electronics, found in everything from smartphones to computers. It uses a small current or voltage at one terminal to control a much larger current flow between the other two, functioning like a tiny, fast electronic switch or amplifier.

A transistor is a semiconductor device that acts as either an electronic switch (turning current on/off) or an amplifier (boosting signals), controlling a larger current with a smaller one, forming the fundamental building block of modern electronics like computers, radios, and smartphones.

Summary

A transistor is a semiconductor device used to amplify or switch electrical signals and power. It is one of the basic building blocks of modern electronics. It is composed of semiconductor material, usually with at least three terminals for connection to an electronic circuit. A voltage or current applied to one pair of the transistor's terminals controls the current through another pair of terminals. Because the controlled (output) power can be higher than the controlling (input) power, a transistor can amplify a signal. Some transistors are packaged individually, but many more in miniature form are found embedded in integrated circuits. Because transistors are the key active components in practically all modern electronics, many people consider them one of the 20th century's greatest inventions.

Physicist Julius Edgar Lilienfeld proposed the concept of a field-effect transistor (FET) in 1925, but it was not possible to construct a working device at that time. The first working device was a point-contact transistor invented in 1947 by physicists John Bardeen, Walter Brattain, and William Shockley at Bell Labs who shared the 1956 Nobel Prize in Physics for their achievement. The most widely used type of transistor, the metal–oxide–semiconductor field-effect transistor (MOSFET), was invented at Bell Labs between 1955 and 1960. Transistors revolutionized the field of electronics and paved the way for smaller and cheaper radios, calculators, computers, and other electronic devices.

Most transistors are made from very pure silicon, and some from germanium, but certain other semiconductor materials are sometimes used. A transistor may have only one kind of charge carrier in a field-effect transistor, or may have two kinds of charge carriers in bipolar junction transistor devices. Compared with the vacuum tube, transistors are generally smaller and require less power to operate. Certain vacuum tubes have advantages over transistors at very high operating frequencies or high operating voltages, such as traveling-wave tubes and gyrotrons. Many types of transistors are made to standardized specifications by multiple manufacturers.

Details

A transistor is a semiconductor device for amplifying, controlling, and generating electrical signals. Transistors are the active components of integrated circuits, or “microchips,” which often contain billions of these minuscule devices etched into their shiny surfaces. Deeply embedded in almost everything electronic, transistors have become the nerve cells of the Information Age.

There are typically three electrical leads in a transistor, called the emitter, the collector, and the base—or, in modern switching applications, the source, the drain, and the gate. An electrical signal applied to the base (or gate) influences the semiconductor material’s ability to conduct electrical current, which flows between the emitter (or source) and collector (or drain) in most applications. A voltage source such as a battery drives the current, while the rate of current flow through the transistor at any given moment is governed by an input signal at the gate—much as a faucet valve is used to regulate the flow of water through a garden hose.

The first commercial applications for transistors were for hearing aids and “pocket” radios during the 1950s. With their small size and low power consumption, transistors were desirable substitutes for the vacuum tubes (known as “valves” in Great Britain) then used to amplify weak electrical signals and produce audible sounds. Transistors also began to replace vacuum tubes in the oscillator circuits used to generate radio signals, especially after specialized structures were developed to handle the higher frequencies and power levels involved. Low-frequency, high-power applications, such as power-supply inverters that convert alternating current (AC) into direct current (DC), have also been transistorized. Some power transistors can now handle currents of hundreds of amperes at electric potentials over a thousand volts.

By far the most common application of transistors today is for computer memory chips—including solid-state multimedia storage devices for electronic games, cameras, and MP3 players—and microprocessors, where millions of components are embedded in a single integrated circuit. Here the voltage applied to the gate electrode, generally a few volts or less, determines whether current can flow from the transistor’s source to its drain. In this case the transistor operates as a switch: if a current flows, the circuit involved is on, and if not, it is off. These two distinct states, the only possibilities in such a circuit, correspond respectively to the binary 1s and 0s employed in digital computers. Similar applications of transistors occur in the complex switching circuits used throughout modern telecommunications systems. The potential switching speeds of these transistors now are hundreds of gigahertz, or more than 100 billion on-and-off cycles per second.

Development of transistors

The transistor was invented in 1947–48 by three American physicists, John Bardeen, Walter H. Brattain, and William B. Shockley, at the American Telephone and Telegraph Company’s Bell Laboratories. The transistor proved to be a viable alternative to the electron tube and, by the late 1950s, supplanted the latter in many applications. Its small size, low heat generation, high reliability, and low power consumption made possible a breakthrough in the miniaturization of complex circuitry. During the 1960s and ’70s, transistors were incorporated into integrated circuits, in which a multitude of components (e.g., diodes, resistors, and capacitors) are formed on a single “chip” of semiconductor material.

Motivation and early radar research