Math Is Fun Forum

You are not logged in.

- Topics: Active | Unanswered

#26 Re: Exercises » Compute the solution: » 2026-01-21 14:11:02

Hi,

2685.

#27 Science HQ » Heart Valve Surgery » 2026-01-20 22:45:10

- Jai Ganesh

- Replies: 0

Heart Valve Surgery

Gist

How is heart valve surgery done?

The surgeon makes a long cut down the centre of your chest, through your breastbone. Your heart is connected to a machine to keep blood flowing around your body during the operation (heart-lung bypass machine). The surgeon cuts into your heart to reach the damaged valve.

Can you walk after heart valve surgery?

People are usually practicing very basic self-care and are encouraged to get up, to breathe deeply and to resume eating, drinking and walking as soon as possible after surgery.

Summary:

What is heart valve surgery?

Heart valve surgery and procedures are performed to repair or replace a valve in the heart that is not working properly because of valvular heart disease (also called heart valve disease). Heart valve surgery is open-heart surgery through the breastbone, into the chest. It is a major operation that can last two hours or longer and recovery often takes several weeks. There are newer, less invasive procedures suitable for some types of valvular heart disease, but they are only done at certain hospitals.

Why is it done?

In a healthy heart, valves control the flow of blood by making it move in one direction through the heart and the body. If a valve is not working correctly, blood flow and the delicate network of blood vessels that carry oxygen throughout the body are affected.

If your valve problem is minor, your doctor may monitor your symptoms or treat you with medication. If your condition is more serious, surgery is usually required to repair or replace the valve to prevent any lasting damage to your heart valve and your heart.

Heart valve surgery and procedures are performed to repair or replace a valve in the heart that is not working properly because of valvular heart disease (also called heart valve disease). Heart valve replacement surgery is open-heart surgery through the breastbone, into the chest. It is a major operation that can last two hours or longer and recovery often takes several weeks. There are newer, less invasive procedures suitable for some types of valvular heart diseases.

In a healthy heart, valves control the flow of blood by making it move in one direction through the heart and the body. The valve can either become stenotic, which means it is narrowed and thus does not allow the blood to flow smoothly from one chamber to another or it starts leaking which hampers the forward flow of blood.

If your valve problem is minor, your doctor may monitor your symptoms or treat you with medication. If your condition is more serious, surgery is usually required to repair or replace the valve to prevent any lasting damage to your heart valve and your heart.

What is Done?

Depending on the problem, there are several different procedures for repairing or replacing valves.

1. Surgical Valve Repair

Surgical procedures are generally used for problems with the mitral or tricuspid valves.

2. Commissurotomy

It is a treatment for a tight valve. The valve flaps (leaflets) are cut to loosen the valve slightly, allowing blood to pass easily.

3. Annuloplasty

It is done for a leaky valve. There is a ring of fibrous tissue at the base of the heart valve called the annulus. To repair an enlarged annulus, sutures are sewn around the ring to make the opening smaller. Or, a ring-like device is attached around the outside of the valve opening to support the valve so it can close more tightly.

4. Valvulotomy

It is a procedure to enlarge narrowed heart valves. It can also be done with the help of a balloon.

5. Non-Surgical Valve Repair

Percutaneous or catheter-based procedures are done without any incisions in the chest or stopping the heart. Instead, a thin flexible tube called a catheter is inserted into a blood vessel in your groin or arm and then threaded through the blood vessels into your heart. Percutaneous or balloon valvuloplasty/valvotomy is used for stiffened or narrowed (stenosed) pulmonary, mitral, or aortic valves. A balloon tip on the end of the catheter is positioned in the narrowed valve and inflated to enlarge the opening. Percutaneous mitral valve repair methods – such as edge-to-edge repair – can fix a leaky mitral valve in a patient who is considered at high risk for surgery. A catheter holding a clip is inserted into the groin and up into the left side of the heart. The open clip is positioned beyond the leaky valve and then pulled back so it catches the flaps (leaflets) of the mitral valve. Once closed, the clip holds the leaflets together and stops the valve from leaking.

Details

Heart valve surgery repairs or replaces a valve that’s too narrow or doesn’t close right. Valves need to work efficiently to help blood flow the right direction through your heart. Heart valve surgery options include open, minimally invasive or through vein access to your heart. It takes one or two months to recover, depending on the surgery.

Overview:

What is heart valve surgery?

Heart valve surgery is an operation that fixes or replaces one or more of the four valves in your heart. Your valves, located between your heart’s four chambers, keep your blood moving the right way. Valves act like doors that open and close with each heartbeat, letting blood flow in and out of the chambers. When valves are working right, your blood should flow through your heart in one direction each time your heart beats.

Your four heart valves are:

* Tricuspid, between your right upper and lower chambers.

* Pulmonary, between your right ventricle (lower chamber) and your pulmonary artery.

* Mitral, between your left upper and lower chambers.

* Aortic, between your left ventricle (lower chamber) and your aorta.

Some of the blood may go back to the chamber or room it just left. Other times, a valve may become narrow, which may prevent blood from moving forward. This is a problem because it keeps your heart from working efficiently. Although heart valve surgery may make you feel fearful, it helps your heart work better. And if your heart’s working better, you’ll feel better, too.

Types of heart valve surgery

The type of heart valve surgery you have will depend on several factors. Your provider will consider:

* Your heart’s structure.

* Your age.

* Other medical conditions you may have.

* Your lifestyle.

Tests will tell your healthcare provider the location, type and extent of your valve disease. Your heart valve issue may have started at birth, or you may have developed a leak, stiffness or narrowing in your valve. The test results help determine the best type of procedure for you.

Your cardiac surgeon can combine valve surgery with other heart surgeries. Examples include surgeries that involve more than one valve procedure and combining heart valve surgery with:

* Bypass surgery.

* Aortic aneurysm surgery.

* Surgery to treat atrial fibrillation.

Heart valve repair surgery

A repair surgery fixes the damaged or faulty valve while preserving much of your own tissue. Surgeons repair mitral valves more than the other valves, but repair surgery can also treat problems with the aortic and tricuspid valves.

Heart valve replacement surgery

Heart valve replacement surgery removes the faulty valve and replaces it with a biological (pig, cow or human tissue) or mechanical (metal or carbon) valve. All valve replacements are biocompatible. That means your immune system won’t reject your new valve. Replacement options include the Ross procedure and minimally invasive procedures like TAVR.

Can a heart valve repair itself?

No, a heart valve can’t repair itself. Valve disease doesn’t go away. It gets worse with time. As the disease gets worse, you’ll have more symptoms and your overall health will suffer. These changes often happen slowly, but they can also occur very quickly.

Depending on the type and extent of valve disease you have, medication may help with symptoms for the short term. Surgery is the only effective long-term solution. Your healthcare provider will help determine when it’s time for surgery.

When is heart valve surgery necessary?

You’ll most likely need heart valve surgery if medicine doesn’t help anymore for symptoms like:

* Chest pain.

* Difficulty breathing.

* Fainting.

Treatment Details:

How should I prepare for heart valve surgery?

You may have tests the day before your surgery. These may include:

* Chest X-ray.

* Echocardiogram.

* Electrocardiogram (EKG).

* CT (computed tomography) scan.

* Cardiac catheterization.

* Blood tests.

Check with your healthcare provider about which medications you can take before surgery. Don’t eat or drink anything after midnight the day of your surgery.

On the day of your procedure, wear loose, comfortable clothes and shoes that are easy to put on. If you wear a bra, you may want to bring one that’s easy to put on without raising your arms. The person who brings you to the hospital can hold on to these items for you during surgery.

Before your surgery, a healthcare provider will shave and clean the area where your surgeon will be working.

What happens during valve surgery on your heart?

During heart valve surgery, a provider will:

* Give you medicine through an IV in your arm or hand so you can sleep deeply and painlessly.

* Use the smallest incision they can for your surgery.

* Set up a machine to take over for your heart and lungs during surgery.

* Repair or replace your heart valve.

* Restart your heart.

* Close your chest.

Heart valve surgery options include:

* Traditional or open-heart surgery: An incision (6 to 8 inches) through your breastbone.

* Minimally invasive heart valve surgery: A smaller incision (3 to 4 inches or smaller). Techniques include endoscopic or keyhole approaches (also called port access, thoracoscopic or video-assisted surgery) and robotic-assisted surgery.

* Transcatheter: Your provider will put a catheter into a larger artery, like your femoral artery in your groin, and do the work without cutting your chest.

How long does this procedure take?

Open-heart surgery for a heart valve replacement can take two to five hours. Repairs or minimally invasive procedures may take less time.

What happens after heart valve surgery?

After surgery, your healthcare team may move you to an intensive care unit (ICU) where they can monitor you closely. After that, you’ll be in a regular room. You may be in the hospital for five to seven days.

Machines connected to you will monitor your blood pressure and heart rate. You may have tubes coming out of your chest to drain fluids.

Your provider will encourage you to eat, drink and walk as soon as you can after surgery. You can start with short walks around your room or down the hall and increase your distance little by little.

Your provider may sign you up for cardiac rehab, a carefully monitored exercise program.

Risks / Benefits:

What are the benefits of heart valve surgery?

Heart valve surgery can ease your symptoms, improve your life expectancy and help prevent death.

The potential advantages of heart valve repair vs. heart valve replacement surgery are:

* Lower risk of infection.

* Less need for lifelong anticoagulant (blood thinning) medication.

* Valve surgeries, including heart valve repair and replacement, are the most common minimally invasive procedure.

The benefits of minimally invasive surgery include:

* Lower chance of infection.

* Less bleeding and trauma.

* Shorter hospital stay.

* Shorter recovery.

* Improved cosmesis (appearance) and smaller wounds.

What are the risks or complications of heart valve surgery?

Any surgery involves risks. Heart valve surgery risks may include:

* Heart attack.

* Heart failure.

* Abnormal heart rhythm — you may need a pacemaker.

* Stroke.

* Blood clots.

* Infection.

* Bleeding.

Risks are related to your age, other medical conditions you may have and how many procedures you have in a single operation. Your cardiologist and surgeon will talk to you about these risks before your surgery.

If you’ve had a valve fixed or replaced, you may be at a higher risk of getting infective endocarditis. But this can also happen with an unrepaired faulty valve. In certain cases, your healthcare provider may prescribe antibiotics to keep you from getting endocarditis from some types of dental work. You can reduce the risk of endocarditis yourself by taking good care of your teeth.

Recovery and Outlook:

How long is recovery after heart valve surgery?

Heart valve surgery recovery takes about four to eight weeks. But your recovery time may be shorter if you had minimally invasive surgery or surgery through a vein.

The way you feel after surgery depends on:

* Which valve was repaired or replaced.

* Your overall health before the surgery.

* Which method your provider used to get to your heart (large incision, small incision or through a vein).

* How the surgery went.

* How well you take care of yourself after surgery.

Caring for yourself after surgery

Recovery after heart valve surgery takes time. Be kind to yourself. Here are some tips:

* Go to your follow-up appointments during recovery so your provider can monitor your progress.

* Don’t take on more than you can handle. You can expect to tire easily for the first three weeks after surgery.

* Don’t drive for a few weeks after surgery.

* Don’t handle anything that weighs more than 15 pounds for the first six to eight weeks after surgery.

* Talk to your provider about when you can go back to work. It’s usually six to 12 weeks after surgery.

What is the survival rate following heart valve surgery?

A study found that people who were more physically active in the year after surgery had a lower risk of death than those who didn’t exercise much. The death rate ranges from 0.1% to 10% depending on the operation and a person's overall health.

When To Call the Doctor:

When should I call my healthcare provider?

Contact your provider if:

* You have chest pain or pain near your incision.

* You feel depressed. This can happen after surgery and can make your recovery take longer.

* You have a fever, which can be a sign of infection.

* You gain more than 5 pounds, which may mean you’re retaining fluid.

Additional Information:

Overview

Heart valve surgery is a procedure to treat heart valve disease. Heart valve disease happens when at least one of the four heart valves is not working properly. Heart valves keep blood flowing in the correct direction through the heart.

The four heart valves are the mitral valve, the tricuspid valve, the pulmonary valve and the aortic valve. Each valve has flaps — called leaflets for the mitral and tricuspid valves and cusps for the aortic and pulmonary valves. These flaps should open and close once during each heartbeat. Valves that don't open and close properly change blood flow through the heart to the body.

In heart valve surgery, a surgeon repairs or replaces the damaged or diseased heart valve or valves. Methods to do this may include open-heart surgery or minimally invasive heart surgery.

The type of heart valve surgery needed depends on age, overall health, and the type and severity of heart valve disease.

Types

* Annuloplasty

* Valvuloplasty

Why it's done

Heart valve surgery is done to treat heart valve disease. There are two basic types of heart valve disease:

* A narrowing of a valve, called stenosis.

* A leak in a valve that allows blood to flow backward, called regurgitation.

You might need heart valve surgery if you have heart valve disease that affects your heart's ability to pump blood.

If you don't have symptoms or if your condition is mild, your healthcare team might suggest regular health checkups. Lifestyle changes and medicines might help manage symptoms.

Sometimes, heart valve surgery may be done even if you don't have symptoms. For example, if you need heart surgery for another condition, surgeons might repair or replace a heart valve at the same time.

Ask your healthcare team whether heart valve surgery is right for you. Ask if minimally invasive heart surgery is an option. It does less damage to the body than does open-heart surgery. If you need heart valve surgery, choose a medical center that has done many heart valve surgeries that include both repair and replacement of the valve.

Risks

Heart valve surgery risks include:

* Bleeding.

* Infection.

* Irregular heart rhythm, called arrhythmia.

* Problem with a replacement valve.

* Heart attack.

* Stroke.

* Death.

How you prepare

Your surgeon and treatment team discuss your heart valve surgery with you and answer any questions. Before you go to the hospital for heart valve surgery, talk with your family or loved ones about your hospital stay. Also discuss what help you'll need when you come home.

Food and medicines

Before you have heart valve surgery, talk to your care team about:

* Any medicines you regularly take and whether you can take them before your surgery.

* Allergies or reactions you've had to medicines.

* When you should stop eating or drinking the night before or the morning of the surgery.

Clothing and personal items

If you're having heart valve surgery, your treatment team might suggest that you bring certain items to the hospital, including:

* A list of your medicines.

* Eyeglasses, hearing aids or dentures.

* Personal care items, such as a brush, a comb, a shaving kit and a toothbrush.

* Loose, comfortable clothing.

* A copy of your advance directive. This is a legal document. It includes instructions about the kinds of treatments you want — or don't want — in case you become unable to express your wishes.

* Items that help you relax, such as portable music players or books.

During heart valve surgery, do not wear:

* Contact lenses.

* Dentures.

* Eyeglasses.

* Jewelry.

* Nail polish.

#28 Re: This is Cool » Miscellany » 2026-01-20 19:31:10

2476) Fractional Distillation

Gist

Fractional distillation is the most common form of separation technology used in petroleum refineries, petrochemical and chemical plants, natural gas processing and cryogenic air separation plants. In most cases, the distillation is operated at a continuous steady state.

Fractional distillation is a method to separate a liquid mixture into its parts (fractions) by heating it, relying on the components' different boiling points, especially when those boiling points are close (less than 25°C apart). It uses a fractionating column with obstacles to create multiple cycles of vaporization and condensation, allowing for a purer separation of components than simple distillation.

Summary

The various components of crude oil have different sizes, weights and boiling temperatures; so, the first step is to separate these components. Because they have different boiling temperatures, they can be separated easily by a process called fractional distillation. The steps of fractional distillation are as follows:

* You heat the mixture of two or more substances (liquids) with different boiling points to a high temperature. Heating is usually done with high pressure steam to temperatures of about 1112 degrees Fahrenheit / 600 degrees Celsius.

* The mixture boils, forming vapor (gases); most substances go into the vapor phase.

* The vapor enters the bottom of a long column (fractional distillation column) that is filled with trays or plates. The trays have many holes or bubble caps (like a loosened cap on a soda bottle) in them to allow the vapor to pass through. They increase the contact time between the vapor and the liquids in the column and help to collect liquids that form at various heights in the column. There is a temperature difference across the column (hot at the bottom, cool at the top).

* The vapor rises in the column.

* As the vapor rises through the trays in the column, it cools.

* When a substance in the vapor reaches a height where the temperature of the column is equal to that substance's boiling point, it will condense to form a liquid. (The substance with the lowest boiling point will condense at the highest point in the column; substances with higher boiling points will condense lower in the column.).

* The trays collect the various liquid fractions.

* The collected liquid fractions may pass to condensers, which cool them further, and then go to storage tanks, or they may go to other areas for further chemical processing.

Fractional distillation is useful for separating a mixture of substances with narrow differences in boiling points, and is the most important step in the refining process.

Very few of the components come out of the fractional distillation column ready for market. Many of them must be chemically processed to make other fractions. For example, only 40% of distilled crude oil is gasoline; however, gasoline is one of the major products made by oil companies. Rather than continually distilling large quantities of crude oil, oil companies chemically process some other fractions from the distillation column to make gasoline; this processing increases the yield of gasoline from each barrel of crude oil.

Details

Fractional distillation is the most common form of separation technology used in petroleum refineries, petrochemical and chemical plants, natural gas processing and cryogenic air separation plants. In most cases, the distillation is operated at a continuous steady state. New feed is always being added to the distillation column and products are always being removed. Unless the process is disturbed due to changes in feed, heat, ambient temperature, or condensing, the amount of feed being added and the amount of product being removed are normally equal. This is known as continuous, steady-state fractional distillation.

Industrial distillation is typically performed in large, vertical cylindrical columns known as "distillation or fractionation towers" or "distillation columns" with diameters ranging from about 0.65 to 6 meters (2 to 20 ft) and heights ranging from about 6 to 60 meters (20 to 197 ft) or more. The distillation towers have liquid outlets at intervals up the column which allow for the withdrawal of different fractions or products having different boiling points or boiling ranges. By increasing the temperature of the product inside the columns, the different products are separated. The "lightest" products (those with the lowest boiling point) exit from the top of the columns and the "heaviest" products (those with the highest boiling point) exit from the bottom of the column.

For example, fractional distillation is used in oil refineries to separate crude oil into useful substances (or fractions) having different hydrocarbons of different boiling points. The crude oil fractions with higher boiling points:

* have more carbon atoms

* have higher molecular weights

* are less branched-chain alkanes

* are darker in color

* are more viscous

* are more difficult to ignite and to burn

Large-scale industrial towers use reflux to achieve a more complete separation of products. Reflux refers to the portion of the condensed overhead liquid product from a distillation or fractionation tower that is returned to the upper part of the tower as shown in the schematic diagram of a typical, large-scale industrial distillation tower. Inside the tower, the reflux liquid flowing downwards provides the cooling needed to condense the vapors flowing upwards, thereby increasing the effectiveness of the distillation tower. The more reflux is provided for a given number of theoretical plates, the better the tower's separation of lower boiling materials from higher boiling materials. Alternatively, the more reflux provided for a given desired separation, the fewer theoretical plates are required.

Crude oil is separated into fractions by fractional distillation. The fractions at the top of the fractionating column have lower boiling points than the fractions at the bottom. All of the fractions are processed further in other refining units.

Fractional distillation is also used in air separation, producing liquid oxygen, liquid nitrogen, and highly concentrated argon. Distillation of chlorosilanes also enable the production of high-purity silicon for use as a semiconductor.

In industrial uses, sometimes a packing material is used in the column instead of trays, especially when low-pressure drops across the column are required, as when operating under vacuum. This packing material can either be random dumped packing (1–3 in (25–76 mm) wide) such as Raschig rings or structured sheet metal. Typical manufacturers are Koch, Sulzer, and other companies. Liquids tend to wet the surface of the packing and the vapors pass across this wetted surface, where mass transfer takes place. Unlike conventional tray distillation in which every tray represents a separate point of vapor liquid equilibrium the vapor-liquid equilibrium curve in a packed column is continuous. However, when modeling packed columns it is useful to compute several "theoretical plates" to denote the separation efficiency of the packed column concerning more traditional trays. Differently shaped packings have different surface areas and porosity. Both of these factors affect packing performance.

Design and operation of a distillation column depends on the feed and desired products. Given a simple, binary component feed, analytical methods such as the McCabe–Thiele method or the Fenske equation can be used. For a multi-component feed, simulation models are used both for design and operation.

Moreover, the efficiencies of the vapor-liquid contact devices (referred to as plates or trays) used in distillation columns are typically lower than that of a theoretical 100% efficient equilibrium stage. Hence, a distillation column needs more plates than the number of theoretical vapor-liquid equilibrium stages.

Reflux refers to the portion of the condensed overhead product that is returned to the tower. The reflux flowing downwards provides the cooling required for condensing the vapors flowing upwards. The reflux ratio, which is the ratio of the (internal) reflux to the overhead product, is conversely related to the theoretical number of stages required for efficient separation of the distillation products. Fractional distillation towers or columns are designed to achieve the required separation efficiently. The design of fractionation columns is normally made in two steps; a process design, followed by a mechanical design. The purpose of the process design is to calculate the number of required theoretical stages and stream flows including the reflux ratio, heat reflux, and other heat duties. The purpose of the mechanical design, on the other hand, is to select the tower internals, column diameter, and height. In most cases, the mechanical design of fractionation towers is not straightforward. For the efficient selection of tower internals and the accurate calculation of column height and diameter, many factors must be taken into account. Some of the factors involved in design calculations include feed load size and properties and the type of distillation column used.

The two major types of distillation columns used are tray and packing columns. Packing columns are normally used for smaller towers and loads that are corrosive or temperature-sensitive or for vacuum service where pressure drop is important. Tray columns, on the other hand, are used for larger columns with high liquid loads. They first appeared on the scene in the 1820s. In most oil refinery operations, tray columns are mainly used for the separation of petroleum fractions at different stages of oil refining.

In the oil refining industry, the design and operation of fractionation towers is still largely accomplished on an empirical basis. The calculations involved in the design of petroleum fractionation columns require in the usual practice the use of numerable charts, tables, and complex empirical equations. In recent years, however, a considerable amount of work has been done to develop efficient and reliable computer-aided design procedures for fractional distillation.

Additional Information

The inside of a fractional distilling column has sets of perforated trays. Each perforation is fitted with a bubble cap. Very hot, vaporized crude oil is pumped into the bottom of the column and rises up through the perforations. The bubble cap forces the oil vapor to bubble through liquid on the tray. This causes the vapor to cool as it flows upward and to condense into liquids. Excess liquid overflows through a pipe called a downcomer to the tray below. At various levels in the column, liquid is drawn off. The heavier products, such as straight-run heavy gas oil, are taken from the bottom part of the column and the lighter products, such as straight-run gasoline, are taken from the top. Straight-run natural gas comes out the top, and straight-run residuum comes out the bottom.

#29 This is Cool » Gemstones » 2026-01-20 18:32:48

- Jai Ganesh

- Replies: 0

Gemstones

Gist

The 12 gemstones, known as birthstones, correspond to each month of the year, with modern lists often including alternatives for some months, featuring Garnet (Jan), Amethyst (Feb), Aquamarine (Mar), Diamond (Apr), Emerald (May), Pearl/Alexandrite (Jun), Ruby (Jul), Peridot (Aug), Sapphire (Sep), Opal/Tourmaline (Oct), Topaz/Citrine (Nov), and Tanzanite/Zircon/Turquoise (Dec), representing different virtues and qualities.

While diamonds are known as the "king of all gems" for their hardness and brilliance, the Ruby is most often called the "King of Gemstones" (or Ratnaraj in Sanskrit) due to its deep red color, rarity, association with royalty, power, and vitality, and highest per-carat price among colored stones. Both hold prestigious titles, but the ruby's fiery red hue and historical significance often earn it the "king" crown.

Goshenite is a colorless gem variety of beryl. It is sometimes called the “mother of all gemstones”because it can be transformed into other gems, such as emerald, morganite, or bixbite. Goshenite is also referred to as the purest form of beryl since there are generally no other elements present in the stone.

Summary

A gemstone is any of various minerals highly prized for beauty, durability, and rarity. A few noncrystalline materials of organic origin (e.g., pearl, red coral, and amber) also are classified as gemstones.

Gemstones have attracted humankind since ancient times, and have long been used for jewelry. The prime requisite for a gem is that it must be beautiful. The beauty may lie in colour or lack of colour; in the latter case, extreme limpidity and “fire” may provide the attraction. Iridescence, opalescence, asterism (the exhibition of a star-shaped figure in reflected light), chatoyance (the exhibition of a changeable lustre and a narrow, undulating band of white light), pattern, and lustre are other features that may make a gemstone beautiful. A gem must also be durable, if the stone is to retain the polish applied to it and withstand the wear and tear of constant handling.

In addition to their use as jewelry, gems were regarded by many civilizations as miraculous and endowed with mysterious powers. Different stones were endowed with different and sometimes overlapping attributes; the diamond, for instance, was thought to give its wearer strength in battle and to protect him against ghosts and magic. Vestiges of such beliefs persist in the modern practice of wearing a birthstone.

Of the more than 2,000 identified natural minerals, fewer than 100 are used as gemstones and only 16 have achieved importance. These are beryl, chrysoberyl, corundum, diamond, feldspar, garnet, jade, lazurite, olivine, opal, quartz, spinel, topaz, tourmaline, turquoise, and zircon. Some of these minerals provide more than one type of gem; beryl, for example, provides emeralds and aquamarines, while corundum provides rubies and sapphires. In virtually all cases, the minerals have to be cut and polished for use in jewelry.

Except for diamond, which presents special problems because of its very great hardness (see diamond cutting), gemstones are cut and polished in any of three ways. Agate, opal, jasper, onyx, chalcedony (all with a Mohs hardness of 7 or less) may be tumbled; that is, they may be placed in a cylinder with abrasive grit and water and the cylinder rotated about its long axis. The stones become polished but are irregular in shape. Second, the same kinds of gemstones may instead be cut en cabochon (i.e., with a rounded upper surface and a flat underside) and polished on water- or motor-driven sandstone wheels. Third, gemstones with Mohs hardness of more than 7 may be cut with a carborundum saw and then mounted in a holder (dop) and pressed against a lathe that can be made to revolve with extreme rapidity. The lathe carries a point or small disk of soft iron, which can vary in diameter from that of a pinhead to a quarter of an inch. The face of the disk is charged with carborundum grit, diamond dust, or other abrasives, along with oil. Another tool used to grind facets is the dental engine, which has greater flexibility and sensitiveness than the lathe. The facets are ground onto the stone using these tools and then are polished as described above.

Of decisive significance for the modern treatment of gemstones was the kind of cutting known as faceting, which produces brilliance by the refraction and reflection of light. Until the late Middle Ages, gems of all kinds were simply cut either en cabochon or, especially for purposes of incrustation, into flat platelets.

The first attempts at cutting and faceting were aimed at improving the appearance of stones by covering natural flaws. Proper cutting depends on a detailed knowledge of the crystal structure of a stone, however. Moreover, it was only in the 15th century that the abrasive property of diamond was discovered and used (nothing else will cut diamond). After this discovery, the art of cutting and polishing diamonds and other gems was developed, probably in France and the Netherlands first. The rose cut was developed in the 17th century, and the brilliant cut, now the general favourite for diamonds, is said to have been used for the first time about 1700.

In modern gem cutting, the cabochon method continues to be used for opaque, translucent, and some transparent stones, such as opal, carbuncle, and so on; but for most transparent gems (especially diamonds, sapphires, rubies, and emeralds), faceted cutting is almost always employed. In this method, numerous facets, geometrically disposed to bring out the beauty of light and colour to the best advantage, are cut. This is done at the sacrifice of material, often to the extent of half the stone or more, but the value of the gem is greatly increased. The four most common faceted forms are the brilliant cut, the step cut, the drop cut, and the rose cut.

In addition to unfaceted stones being cabochon cut, some are engraved. High-speed, diamond-tipped cutting tools are used. The stone is hand-held against the tool, with the shape, symmetry, size, and depth of cut being determined by eye. Gemstones can also be made by cementing several smaller stones together to create one large jewel.

In some cases, the colour of gemstones is also enhanced. This is accomplished by any of three methods: heating under controlled conditions, exposure to X rays or radium, or the application of pigment or coloured foil to the pavilion (base) facets.

In recent times various kinds of synthetic gems, including rubies, sapphires, and emeralds, have been produced. Two methods of fabrication are currently employed, one involving crystal growth from solution and the other crystal growth from melts.

Details

A gemstone (also called a fine gem, jewel, precious stone, semiprecious stone, or simply gem) is a piece of mineral crystal which, when cut or polished, is used to make jewelry or other adornments. Certain rocks (such as lapis lazuli, opal, and obsidian) and occasionally organic materials that are not minerals (such as amber, jet, and pearl) may also be used for jewelry and are therefore often considered to be gemstones as well. Most gemstones are hard, but some softer minerals such as brazilianite may be used in jewelry because of their color or luster or other physical properties that have aesthetic value. However, generally speaking, soft minerals are not typically used as gemstones by virtue of their brittleness and lack of durability.

Found all over the world, the industry of coloured gemstones (i.e. anything other than diamonds) is currently estimated at US$1.55 billion as of 2023 and is projected to steadily increase to a value of $4.46 billion by 2033.

A gem expert is a gemologist, a gem maker is called a lapidarist or gemcutter; a diamond cutter is called a diamantaire.

Characteristics and classification

A collection of gemstone pebbles made by tumbling the rough stones, except the ruby and tourmaline, with abrasive grit inside a rotating barrel. The largest pebble here is 40 mm (1.6 in) long.

The traditional classification in the West, which goes back to the ancient Greeks, begins with a distinction between precious and semi-precious; similar distinctions are made in other cultures. In modern use, the precious stones are emerald, ruby, sapphire and diamond, with all other gemstones being semi-precious. This distinction reflects the rarity of the respective stones in ancient times, as well as their quality: all are translucent, with fine color in their purest forms (except for the colorless diamond), and very hard with a hardness score of 8 to 10 on the Mohs scale. Other stones are classified by their color, translucency, and hardness. The traditional distinction does not necessarily reflect modern values; for example, while most garnets are relatively inexpensive, a green garnet called tsavorite can be far more valuable than a mid-quality emerald. Another traditional term for semi-precious gemstones used in art history and archaeology is hardstone. The use of the terms "precious" and "semi-precious" in a commercial context is arguably misleading, as it suggests that certain stones are more valuable than others, which is not always reflected in their actual market value—although the terms may generally be accurate when referring to desirability.

In modern times gemstones are identified by gemologists, who describe gems and their characteristics using technical terminology specific to the field of gemology. The first characteristic a gemologist uses to identify a gemstone is its chemical composition. For example, diamonds are made of carbon (C), while sapphires and rubies are made of aluminium oxide (Al2O3). Many gems are crystals which are classified by their crystal system such as cubic or trigonal or monoclinic. Another term used is habit, the form the gem is usually found in. For example, diamonds, which have a cubic crystal system, are often found as octahedrons.

Gemstones are classified into different groups, species, and varieties. For example, ruby is the red variety of the species corundum, while any other color of corundum is considered sapphire. Other examples of beryl varieties include emerald (green), aquamarine (blue), red beryl (red), goshenite (colorless), heliodor (yellow), and morganite (pink).

Gems are characterized in terms of their color (hue, tone and saturation), optical phenomena, luster, refractive index, birefringence, dispersion, specific gravity, hardness, cleavage, and fracture. They may exhibit pleochroism or double refraction. They may have luminescence and a distinctive absorption spectrum. Gemstones may also be classified in terms of their "water". This is a recognized grading of the gem's luster, transparency, or "brilliance". Very transparent gems are considered "first water", while "second" or "third water" gems are those of a lesser transparency. Additionally, material or flaws within a stone may be present as inclusions.

Value

Gemstones have no universally accepted grading system. Diamonds are graded using a system developed by the Gemological Institute of America (GIA) in the early 1950s. Historically, all gemstones were graded using the naked eye. The GIA system included a major innovation: the introduction of 10x magnification as the standard for grading clarity. Other gemstones are still graded using the naked eye (assuming 20/20 vision).

A mnemonic device, the "four Cs" (color, cut, clarity, and carats), has been introduced to help describe the factors used to grade a diamond. With modification, these categories can be useful in understanding the grading of all gemstones. The four criteria carry different weights depending upon whether they are applied to colored gemstones or to colorless diamonds. In diamonds, the cut is the primary determinant of value, followed by clarity and color. An ideally cut diamond will sparkle, to break down light into its constituent rainbow colors (dispersion), chop it up into bright little pieces (scintillation), and deliver it to the eye (brilliance). In its rough crystalline form, a diamond will do none of these things; it requires proper fashioning and this is called "cut". In gemstones that have color, including colored diamonds, the purity, and beauty of that color is the primary determinant of quality.

Physical characteristics that make a colored stone valuable are color, clarity to a lesser extent (emeralds will always have a number of inclusions), cut, unusual optical phenomena within the stone such as color zoning (the uneven distribution of coloring within a gem) and asteria (star effects).

Apart from the more generic and commonly used gemstones such as from diamonds, rubies, sapphires, and emeralds, pearls and opal have also been defined as precious in the jewellery trade. Up to the discoveries of bulk amethyst in Brazil in the 19th century, amethyst was considered a "precious stone" as well, going back to ancient Greece. Even in the last century certain stones such as aquamarine, peridot and cat's eye (cymophane) have been popular and hence been regarded as precious, thus reinforcing the notion that a mineral's rarity may have been implicated in its classification as a precious stone and thus contribute to its value.

Today the gemstone trade no longer makes such a distinction. Many gemstones are used in even the most expensive jewelry, depending on the brand-name of the designer, fashion trends, market supply, treatments, etc. Nevertheless, diamonds, rubies, sapphires, and emeralds still have a reputation that exceeds those of other gemstones.

Rare or unusual gemstones, generally understood to include those gemstones which occur so infrequently in gem quality that they are scarcely known except to connoisseurs, include andalusite, axinite, cassiterite, clinohumite, painite and red beryl.

Gemstone pricing and value are governed by factors and characteristics in the quality of the stone. These characteristics include clarity, rarity, freedom from defects, the beauty of the stone, as well as the demand for such stones. There are different pricing influencers for both colored gemstones, and for diamonds. The pricing on colored stones is determined by market supply-and-demand, but diamonds are more intricate.

In the addition to the aesthetic and adorning/ornamental purpose of gemstones, there are proponents of energy medicine who also value gemstones on the basis of their alleged healing powers.

Additional Information

Gemstone symbolism refers to the cultural, historical, and spiritual associations between specific gemstones and concepts like healing, protection, love, and strength. This tradition dates back to ancient civilizations, where gemstones were prized not only for their beauty but for their perceived metaphysical properties. These beliefs influenced how gemstones were used — from royal jewelry and religious artifacts to personal talismans and medicinal treatments.

Today, many people choose gemstones based on these symbolic meanings to guide their purchases or for personal reasons, whether for birthstone jewelry or engagement rings.

#30 Re: Dark Discussions at Cafe Infinity » crème de la crème » 2026-01-20 16:56:02

2415) Melvin Calvin

Gist:

Work

One of the most fundamental processes of life is photosynthesis. Green plants use energy from sunlight to make carbohydrates out of water and carbon dioxide in the air. Through studies during the early 1950s, particularly of single-cell green algae, Melvin Calvin and his colleagues traced the path taken by carbon through different stages of photosynthesis. For this they made use of tools such as radioactive isotopes and chromatography. Their findings included insight into the important role played by phosphorous compounds during the composition of carbohydrates.

Summary

Melvin Ellis Calvin (April 8, 1911 – January 8, 1997) was an American biochemist known for discovering the Calvin cycle along with Andrew Benson and James Bassham, for which he was awarded the 1961 Nobel Prize in Chemistry. He spent most of his five-decade career at the University of California, Berkeley.

Early life and education

Melvin Calvin was born in St. Paul, Minnesota, the son of Elias Calvin and Rose Herwitz, Jewish immigrants from the Russian Empire (now known as Lithuania and Georgia).

At an early age, Melvin Calvin’s family moved to Detroit, Michigan where his parents ran a grocery store to earn their living. Melvin Calvin was often found exploring his curiosity by looking through all of the products that made up their shelves.

After he graduated from Central High School in 1928, he went on to study at Michigan College of Mining and Technology (now known as Michigan Technological University) where he received the school’s first Bachelors of Science in Chemistry. He went on to earn his PhD at the University of Minnesota in 1935. While under the mentorship of George Glocker, he studied and wrote his thesis on the electron affinity of halogens. He was invited to join the lab of Michael Polanyi as a Post Doctoral student at the University of Manchester. The two years he spent at the lab were focused on studying the structure and behavior of organic molecules. In 1942, He married Marie Genevieve Jemtegaard, and they had three daughters, Elin, Sowie, and Karole, and a son, Noel.

Career

On a visit to the University of Manchester, Joel Hildebrand, the director of UC Radiation Laboratory, invited Calvin to join the faculty at the University of California, Berkeley. This made him the first non-Berkeley graduate hired by the chemistry department in +25 years. He invited Calvin to push forward in radioactive carbon research because "now was the time". Calvin's original research at UC Berkeley was based on the discoveries of Martin Kamen and Sam Ruben in long-lived radioactive carbon-14 in 1940.

In 1947, he was promoted to a Professor of Chemistry and the director of the Bio-Organic Chemistry group in the Lawrence Radiation Laboratory. The team he formed included: Andrew Benson, James A. Bassham, and several others. Andrew Benson was tasked with setting up the photosynthesis laboratory. The purpose of this lab was to discover the path of carbon fixation through the process of photosynthesis. The greatest impact of the research was discovering the way that light energy converts into chemical energy. Using the carbon-14 isotope as a tracer, Calvin, Andrew Benson and James Bassham mapped the complete route that carbon travels through a plant during photosynthesis, starting from its absorption as atmospheric carbon dioxide to its conversion into carbohydrates and other organic compounds. The process is part of the photosynthesis cycle. It was given the name the Calvin–Benson–Bassham Cycle, named for the work of Melvin Calvin, Andrew Benson, and James Bassham. There were many people who contributed to this discovery but ultimately Melvin Calvin led the charge.

In 1963, Calvin was given the additional title of Professor of Molecular Biology. He was founder and Director of the Laboratory of Chemical Biodynamics, known as the “Roundhouse”, and simultaneously Associate Director of Berkeley Radiation Laboratory, where he conducted much of his research until his retirement in 1980. In his final years of active research, he studied the use of oil-producing plants as renewable sources of energy. He also spent many years testing the chemical evolution of life and wrote a book on the subject that was published in 1969.

Details

Melvin Calvin (born April 8, 1911, St. Paul, Minnesota, U.S.—died January 8, 1997, Berkeley, California) was an American biochemist who received the 1961 Nobel Prize for Chemistry for his discovery of the chemical pathways of photosynthesis.

Calvin was the son of immigrant parents. His father was from Kalvaria, Lithuania, so the Ellis Island immigration authorities renamed him Calvin; his mother was from Russian Georgia. Soon after his birth, the family moved to Detroit, Michigan, where Calvin showed an early interest in science, especially chemistry and physics. In 1927 he received a full scholarship from the Michigan College of Mining and Technology (now Michigan Technological University) in Houghton, where he was the school’s first chemistry major. Few chemistry courses were offered, so he enrolled in mineralogy, geology, paleontology, and civil engineering courses, all of which proved useful in his later interdisciplinary scientific research. Following his sophomore year, he interrupted his studies for a year, earning money as an analyst in a brass factory.

Calvin earned a bachelor’s degree in 1931, and then he attended the University of Minnesota in Minneapolis, from which he received a doctorate in 1935 with a dissertation on the electron affinity of halogen atoms. With a Rockefeller Foundation grant, he researched coordination catalysis, activation of molecular hydrogen, and metalloporphyrins (porphyrin and metal compounds) at the University of Manchester in England with Michael Polanyi, who introduced him to the interdisciplinary approach. In 1937 Calvin joined the faculty of the University of California, Berkeley, as an instructor. (He was the first chemist trained elsewhere to be hired by the school since 1912.) He rose through the ranks to become director (1946) of the bioorganic chemistry group at the school’s Lawrence Radiation Laboratory (now the Lawrence Livermore National Laboratory), director of the Laboratory of Chemical Biodynamics (1963), associate director of Lawrence Livermore (1967), and University Professor of Chemistry (1971).

At Berkeley, Calvin continued his work on hydrogen activation and began work on the colour of organic compounds, leading him to study the electronic structure of organic molecules. In the early 1940s, he worked on molecular genetics, proposing that hydrogen bonding is involved in the stacking of nucleic acid bases in chromosomes. During World War II, he worked on cobalt complexes that bond reversibly with oxygen to produce an oxygen-generating apparatus for submarines or destroyers. In the Manhattan Project, he employed chelation and solvent extraction to isolate and purify plutonium from other fission products of uranium that had been irradiated. Although not developed in time for wartime use, his technique was later used for laboratory separations.

In 1942 Calvin married Genevieve Jemtegaard, with later Nobel chemistry laureate Glenn T. Seaborg as best man. The married couple collaborated on an interdisciplinary project to investigate the chemical factors in the Rh blood group system. Genevieve was a juvenile probation officer, but, according to Calvin’s autobiography, “she spent a great deal of time actually in the laboratory working with the antigenic material. This was her first chemical laboratory experience but not her last by any means.” Together they helped to determine the structure of one of the Rh antigens, which they named elinin for their daughter Elin. Following the oil embargo after the 1973 Arab-Israeli War, they sought suitable plants, e.g., genus Euphorbia, to convert solar energy to hydrocarbons for fuel, but the project failed to be economically feasible.

In 1946 Calvin began his Nobel prize-winning work on photosynthesis. After adding carbon dioxide with trace amounts of radioactive carbon-14 to an illuminated suspension of the single-cell green alga Chlorella pyrenoidosa, he stopped the alga’s growth at different stages and used paper chromatography to isolate and identify the minute quantities of radioactive compounds. This enabled him to identify most of the chemical reactions in the intermediate steps of photosynthesis—the process in which carbon dioxide is converted into carbohydrates. He discovered the “Calvin cycle,” in which the “dark” photosynthetic reactions are impelled by compounds produced in the “light” reactions that occur on absorption of light by chlorophyll to yield oxygen. Also using isotopic tracer techniques, he followed the path of oxygen in photosynthesis. This was the first use of a carbon-14 tracer to explain a chemical pathway.

Calvin’s research also included work on electronic, photoelectronic, and photochemical behaviour of porphyrins; chemical evolution and organic geochemistry, including organic constituents of lunar rocks for the U.S. National Aeronautics and Space Administration (NASA); free radical reactions; the effect of deuterium (“heavy hydrogen”) on biochemical reactions; chemical and viral carcinogenesis; artificial photosynthesis (“synthetic chloroplasts”); radiation chemistry; the biochemistry of learning; brain chemistry; philosophy of science; and processes leading to the origin of life.

Calvin’s bioorganic group eventually required more space, so he designed the new Laboratory of Chemical Biodynamics (the “Roundhouse” or “Calvin Carousel”). This circular building contained open laboratories and numerous windows but few walls to encourage the interdisciplinary interaction that he had carried out with his photosynthesis group at the old Radiation Laboratory. He directed this laboratory until his mandatory age retirement in 1980, when it was renamed the Melvin Calvin Laboratory. Although officially retired, he continued to come to his office until 1996 to work with a small research group.

Calvin was the author of more than 600 articles and 7 books, and he was the recipient of several honorary degrees from U.S. and foreign universities. His numerous awards included the Priestley Medal (1978), the American Chemical Society’s highest award, and the U.S. National Medal of Science (1989), the highest U.S. civilian scientific award.

#31 Science HQ » Skeleton » 2026-01-20 16:29:12

- Jai Ganesh

- Replies: 0

Skeleton

Gist

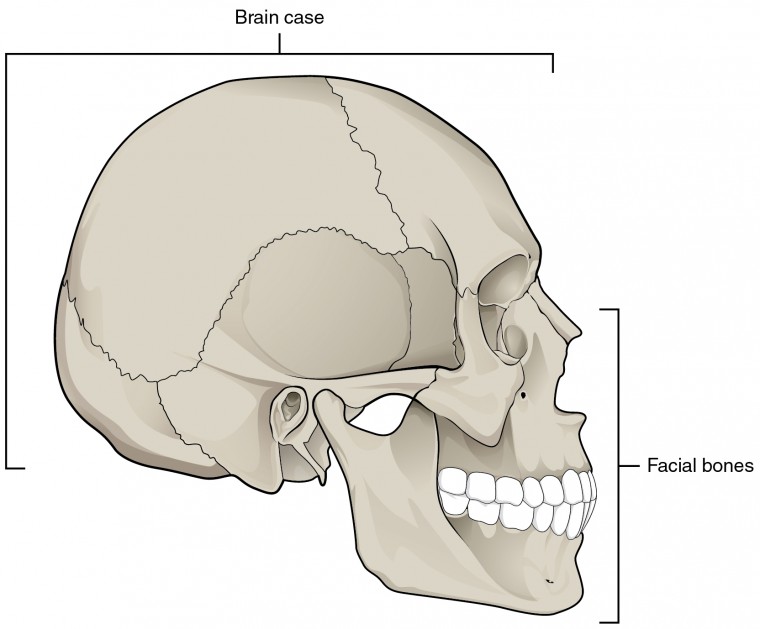

A skeleton is the rigid framework of bones and cartilage that supports an organism's body, protects internal organs, and allows for movement; it can be internal (endoskeleton, like in humans and vertebrates) or external (exoskeleton, like in insects). The human skeleton, specifically, is an internal structure with 206 bones in adulthood, divided into the axial (skull, spine, ribs) and appendicular (limbs, girdles) parts, working with ligaments, tendons, and cartilage to provide shape, support, and facilitate motion.

A skeletal system is necessary to support the body, protect internal organs, and allow for the movement of an organism. There are three different skeleton designs that fulfill these functions: hydrostatic skeleton, exoskeleton, and endoskeleton.

Summary

A skeleton is the structural frame that supports the body of most animals. There are several types of skeletons, including the exoskeleton, which is a rigid outer shell that holds up an organism's shape; the endoskeleton, a rigid internal frame to which the organs and soft tissues attach; and the hydroskeleton, a flexible internal structure supported by the hydrostatic pressure of body fluids.

Vertebrates are animals with an endoskeleton centered around an axial vertebral column, and their skeletons are typically composed of bones and cartilages. Invertebrates are other animals that lack a vertebral column, and their skeletons vary, including hard-shelled exoskeleton (arthropods and most molluscs), plated internal shells (e.g. cuttlebones in some cephalopods) or rods (e.g. ossicles in echinoderms), hydrostatically supported body cavities (most), and spicules (sponges). Cartilage is a rigid connective tissue that is found in the skeletal systems of vertebrates and invertebrates.

Details

Human skeleton is the internal skeleton that serves as a framework for the body. This framework consists of many individual bones and cartilages. There also are bands of fibrous connective tissue—the ligaments and the tendons—in intimate relationship with the parts of the skeleton. This article is concerned primarily with the gross structure and the function of the skeleton of the normal human adult.

The human skeleton, like that of other vertebrates, consists of two principal subdivisions, each with origins distinct from the others and each presenting certain individual features. These are (1) the axial, comprising the vertebral column—the spine—and much of the skull, and (2) the appendicular, to which the pelvic (hip) and pectoral (shoulder) girdles and the bones and cartilages of the limbs belong. A third subdivision, the visceral (splanchnocranium), comprises the lower jaw, some elements of the upper jaw, and the branchial arches, including the hyoid bone.

When one considers the relation of these subdivisions of the skeleton to the soft parts of the human body—such as the nervous system, the digestive system, the respiratory system, the cardiovascular system, and the voluntary muscles of the muscle system—it is clear that the functions of the skeleton are of three different types: support, protection, and motion. Of these functions, support is the most primitive and the oldest; likewise, the axial part of the skeleton was the first to evolve. The vertebral column, corresponding to the notochord in lower organisms, is the main support of the trunk.

The central nervous system lies largely within the axial skeleton, the brain being well protected by the cranium and the spinal cord by the vertebral column, by means of the bony neural arches (the arches of bone that encircle the spinal cord) and the intervening ligaments.

A distinctive characteristic of humans as compared with other mammals is erect posture. The human body is to some extent like a walking tower that moves on pillars, represented by the legs. Tremendous advantages have been gained from this erect posture, the chief among which has been the freeing of the arms for a great variety of uses. Nevertheless, erect posture has created a number of mechanical problems—in particular, weight bearing. These problems have had to be met by adaptations of the skeletal system.

Protection of the heart, lungs, and other organs and structures in the chest creates a problem somewhat different from that of the central nervous system. These organs, the function of which involves motion, expansion, and contraction, must have a flexible and elastic protective covering. Such a covering is provided by the bony thoracic basket, or rib cage, which forms the skeleton of the wall of the chest, or thorax. The connection of the ribs to the breastbone—the sternum—is in all cases a secondary one, brought about by the relatively pliable rib (costal) cartilages. The small joints between the ribs and the vertebrae permit a gliding motion of the ribs on the vertebrae during breathing and other activities. The motion is limited by the ligamentous attachments between ribs and vertebrae.

The third general function of the skeleton is that of motion. The great majority of the skeletal muscles are firmly anchored to the skeleton, usually to at least two bones and in some cases to many bones. Thus, the motions of the body and its parts, all the way from the lunge of the football player to the delicate manipulations of a handicraft artist or of the use of complicated instruments by a scientist, are made possible by separate and individual engineering arrangements between muscle and bone.

Additional Information

The skeleton is a remarkable organ that provides the body with a frame that is strong enough for protection, light enough for mobility, and adaptable for changing structural needs. The skeleton also serves metabolic functions as a storehouse for calcium and phosphorus, a buffering site for hydrogen ion excess, and a binding site for toxic ions such as lead and aluminum. When skeletal tissues are required to fulfill these latter functions, this may occur at the cost of structural integrity and lead to fractures. Once the adult skeleton has been formed, both the structural and metabolic functions are carried out largely by remodeling—removal and replacement of bone tissue at the same site in so-called bone multicellular units (BMU)—rather than modeling, which is formation of bone at sites where no prior resorption has occurred. Both processes do continue throughout life, however. In particular, modeling in the form of new periosteal apposition can occur with aging as a compensatory mechanism to the weakening of bone by the trabecular and endosteal loss and cortical porosity that occurs with increased resorption and inadequate formation in BMUs.

#32 Re: Jai Ganesh's Puzzles » General Quiz » 2026-01-20 15:47:01

Hi,

#10709. What does the term in Geography Cordillera mean?

#10710. What does the term in Geography Snow cornice mean?

#33 Re: Jai Ganesh's Puzzles » English language puzzles » 2026-01-20 15:26:02

Hi,

#5905. What does the noun matron mean?

#5906. What does the noun matting mean?

#34 Re: Jai Ganesh's Puzzles » Doc, Doc! » 2026-01-20 15:13:34

Hi,

#2549. What does the medical term Lancefield grouping mean?

#35 Dark Discussions at Cafe Infinity » Colleges Quotes - I » 2026-01-20 15:03:30

- Jai Ganesh

- Replies: 0

Colleges Quotes - I

1. And I think it's that time. And I think if you just step aside and Mr. Romney can kind of take over. You can maybe still use a plane. Though maybe a smaller one. Not that big gas guzzler you are going around to colleges and talking about student loans and stuff like that. - Clint Eastwood

2. Let reverence for the laws be breathed by every American mother to the lisping babe that prattles on her lap - let it be taught in schools, in seminaries, and in colleges; let it be written in primers, spelling books, and in almanacs; let it be preached from the pulpit, proclaimed in legislative halls, and enforced in courts of justice. - Abraham Lincoln

3. There's a level of service that we could provide when we're just at Harvard that we can't provide for all of the colleges, and there's a level of service that we can provide when we're a college network that we wouldn't be able to provide if we went to other types of things. - Mark Zuckerberg

4. With the changing economy, no one has lifetime employment. But community colleges provide lifetime employability. - Barack Obama

5. I've fought against transnational gangs. I took on the biggest banks and helped take down one of the biggest for-profit colleges. I know a predator when I see one. - Kamala Harris

6. I think, my own personal view is there should be higher and higher levels of autonomy; government should not interfere in setting up colleges, in running colleges. The market, the society will decide which is a good university, which is not a good university, rather than government mandating. - N. R. Narayana Murthy

7. Community colleges play an important role in helping people transition between careers by providing the retooling they need to take on a new career. - Barack Obama

8. There's a reasonable amount of traction in college education, particularly engineering, because quite a lot of that is privatized, so there is an incentive to set up new colleges of reasonably high quality. - Azim Premji.

#36 Jokes » Cherry Jokes - I » 2026-01-20 14:29:30

- Jai Ganesh

- Replies: 0

Q: Which show lets fruits fight each other?

A: Cherry Springer.

* * *

Q: What Saturday morning cartoon do fruits watch?

A: Tom and Cherry.

* * *

Patient: Doctor, there is a cherry growing out of my head.

Doctor: Oh, that's easy. Just put some cream on it and have a jubilee!

* * *

Q: Why did the cherry go to the chocolate factory?

A: It was cordially invited.

* * *

Q: What do you call a fruit that owns a football team?

A: Cherry Jones.

* * *

#37 Re: Jai Ganesh's Puzzles » 10 second questions » 2026-01-20 14:23:36

Hi,

#9833.

#38 Re: Jai Ganesh's Puzzles » Oral puzzles » 2026-01-20 14:12:42

Hi,

#6327.

#39 Re: Exercises » Compute the solution: » 2026-01-20 13:57:17

Hi,

2684.

#40 This is Cool » Insect Repellent » 2026-01-19 23:21:25

- Jai Ganesh

- Replies: 0

Insect Repellent

Gist

What is an insect repellent?

Not only are they irritating, but many insects are also carriers of dangerous diseases such as malaria, dengue, Zika virus, and Lyme disease. This is where insect repellents come into play. Insect repellents are substances designed to keep insects away from humans, reducing the chance of bites and disease transmission.

For more than 60 years, DEET has reigned as the undisputed champion of insect repellents. No longer. There's now a potentially better alternative on the market: picaridin. Both DEET and picaridin are proven to be effective at fending off ticks—and are superior to other repellents when it comes to protection time.

(N,N-Diethyl-meta-toluamide, also called diethyltoluamide or DEET).

Summary

The 3 major reasons to use insect repellents are: 1) new threats to human health posed by emerging and imported arthropod-borne infectious diseases; 2) the dominance of new, competent insect vectors of infectious diseases; and 3) the inability to primarily prevent the transmission of most arthropod-borne infection diseases by vaccinations with the exceptions of yellow fever vaccine in South America and Africa, Japanese encephalitis vaccine in Southeast Asia, and several regional tick-borne virus vaccines in Eastern Europe.

For many people, applying insect repellents may be the most effective and easiest way to protect against arthropod bites. The search for the ‘perfect’ insect repellent has been ongoing for decades, and has yet to be achieved. The ideal agent would: repel multiple species of biting arthropods; remain effective for at least 8 h; cause no irritation to skin or mucous membranes; possess no systemic toxicity; be resistant to abrasion and washoff; and be greaseless and odorless. No presently-available insect repellent meets all of these criteria. Efforts to find such a compound have been hampered by the multiplicity of variables that affect the inherent repellency of any chemical. Repellents do not all share a single mode of action, and different species of insects may react differently to the same repellent.

To be effective as an insect repellent, a chemical must be volatile enough to maintain an effective repellent vapor concentration at the skin surface, but not evaporate so rapidly that it quickly loses its effectiveness. Multiple factors play a role in effectiveness, including concentration, frequency and uniformity of application, the user's activity level and inherent attractiveness to blood-sucking arthropods, and the number and species of the organisms trying to bite. Gender may also play a role in how well a repellent works – one study has shown that DEET-based repellents worked less well in women than in men. The effectiveness of any repellent is reduced by abrasion from clothing; evaporation and absorption from the skin surface; washoff from sweat, rain, or water; and a windy environment. Each 10°C increase in ambient temperature can lead to as much as 50% reduction in protection time, due to greater evaporative loss of the repellent from the skin surface. One of the greatest limitations of insect repellents is that they do not ‘cloak’ the user in a chemical veil of protection; any untreated exposed skin will be readily bitten by hungry arthropods.

Details

An insect repellent (also commonly called "bug spray" or "bug deterrent") is a substance applied to the skin, clothing, or other surfaces to discourage insects (and arthropods in general) from landing or climbing on that surface. Insect repellents help prevent and control the outbreak of insect-borne (and other arthropod-bourne) diseases such as malaria, Lyme disease, dengue fever, bubonic plague, river blindness, and West Nile fever. Pest animals commonly serving as vectors for disease include insects such as flea, fly, and mosquito; and ticks (arachnids).

Some insect repellents are insecticides (bug killers), but most simply discourage insects and send them flying or crawling away.

Effectiveness

Synthetic repellents tend to be more effective and/or longer lasting than "natural" repellents.

For protection against ticks and mosquito bites, the U.S. Centers for Disease Control (CDC) recommends DEET, icaridin (picaridin, KBR 3023), oil of lemon eucalyptus (OLE), para-menthane-diol (PMD), IR3535 and 2-undecanone with the caveat that higher percentages of the active ingredient provide longer protection.

In 2015, researchers at New Mexico State University tested 10 commercially available products for their effectiveness at repelling mosquitoes. The known active ingredients tested included DEET (at various concentrations), geraniol, p-menthane-3-8-diol (found in lemon eucalyptus oil), thiamine, and several oils (soybean, rosemary, cinnamon, lemongrass, citronella, and lemon eucalyptus). Two of the products tested were fragrances where the active ingredients were unknown. On the mosquito Aedes aegypti, only one repellent that did not contain DEET had a strong effect for the duration of the 240 minutes test: a lemon eucalyptus oil repellent. However, Victoria's Secret Bombshell, a perfume not advertised as an insect repellent, performed effectively during the first 120 minutes after application.

In one comparative study from 2004, IR3535 was as effective or better than DEET in protection against Aedes aegypti and Culex quinquefasciatus mosquitoes. Other sources (official publications of the associations of German physicians as well as of German druggists) suggest the contrary and state DEET is still the most efficient substance available and the substance of choice for stays in malaria regions, while IR3535 has little effect. However, some plant-based repellents may provide effective relief as well. Essential oil repellents can be short-lived in their effectiveness.

A test of various insect repellents by an independent consumer organization found that repellents containing DEET or icaridin are more effective than repellents with "natural" active ingredients. All the synthetics gave almost 100% repellency for the first 2 hours, where the natural repellent products were most effective for the first 30 to 60 minutes, and required reapplication to be effective over several hours.

Although highly toxic to cats, permethrin is recommended as protection against mosquitoes for clothing, gear, or bed nets. In an earlier report, the CDC found oil of lemon eucalyptus to be more effective than other plant-based treatments, with a similar effectiveness to low concentrations of DEET. However, a 2006 published study found in both cage and field studies that a product containing 40% oil of lemon eucalyptus was just as effective as products containing high concentrations of DEET. Research has also found that neem oil is mosquito repellent for up to 12 hours. Citronella oil's mosquito repellency has also been verified by research, including effectiveness in repelling Aedes aegypti, but requires reapplication after 30 to 60 minutes.

There are also products available based on sound production, particularly ultrasound (inaudibly high-frequency sounds) which purport to be insect repellents. However, these electronic devices have been shown to be ineffective based on studies done by the United States Environmental Protection Agency and many universities.

Safety issues:

For humans

Children may be at greater risk for adverse reactions to repellents, in part, because their exposure may be greater. Children can be at greater risk of accidental eye contact or ingestion. As with chemical exposures in general, pregnant women should take care to avoid exposures to repellents when practical, as the fetus may be vulnerable.

Some experts also recommend against applying chemicals such as DEET and sunscreen simultaneously since that would increase DEET penetration. Canadian researcher, Xiaochen Gu, a professor at the University of Manitoba's faculty of Pharmacy who led a study about mosquitos, advises that DEET should be applied 30 or more minutes later. Gu also recommends insect repellent sprays instead of lotions which are rubbed into the skin "forcing molecules into the skin".

Regardless of which repellent product used, it is recommended to read the label before use and carefully follow directions. Usage instructions for repellents vary from country to country. Some insect repellents are not recommended for use on younger children.

In the DEET Reregistration Eligibility Decision (RED) the United States Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) reported 14 to 46 cases of potential DEET associated seizures, including 4 deaths. The EPA states: "... it does appear that some cases are likely related to DEET toxicity", but observed that with 30% of the US population using DEET, the likely seizure rate is only about one per 100 million users.

The Pesticide Information Project of Cooperative Extension Offices of Cornell University states that, "Everglades National Park employees having extensive DEET exposure were more likely to have insomnia, mood disturbances and impaired cognitive function than were lesser exposed co-workers".

The EPA states that citronella oil shows little or no toxicity and has been used as a topical insect repellent for 60 years. However, the EPA also states that citronella may irritate skin and cause dermatitis in certain individuals. Canadian regulatory authorities concern with citronella based repellents is primarily based on data-gaps in toxicology, not on incidents.

Within countries of the European Union, implementation of Regulation 98/8/EC, commonly referred to as the Biocidal Products Directive, has severely limited the number and type of insect repellents available to European consumers. Only a small number of active ingredients have been supported by manufacturers in submitting dossiers to the EU Authorities.

In general, only formulations containing DEET, icaridin (sold under the trade name Saltidin and formerly known as Bayrepel or KBR3023), IR3535 and citriodiol (p-menthane-3,8-diol) are available. Most "natural" insect repellents such as citronella, neem oil, and herbal extracts are no longer permitted for sale as insect repellents in the EU due to their lack of effectiveness; this does not preclude them from being sold for other purposes, as long as the label does not indicate they are a biocide (insect repellent).

Toxicity for other animals

A 2018 study found that icaridin is highly toxic to salamander larvae, in what the authors described as conservative exposure doses. The LC50 standard was additionally found to be completely inadequate in the context of finding this result.

Permethrin is highly toxic to cats but not to dogs or humans.

Additional Information

Warmer weather means more chances for kids to go outside to play, hike and enjoy the fresh air with family and friends. Warmer weather also means preventing insect bites.

Biting insects such as mosquitoes and biting flies can make children miserable. More worrisome is that bites from some insects can cause serious illnesses.

Preventing insect bites

Depending on where you live, you may already be familiar with illnesses that spread from insects to people. For example, Lyme disease, West Nile disease and Zika spread through the bite of a mosquito or tick. Recently, these insect-borne illnesses have been on the rise due, in part, to the effects of climate change.

One way to protect your child from biting insects is to use insect repellents. Choose an insect repellent that is effective at preventing bites from insects commonly found where you live. Follow the instructions on the label for proper use.

Keep in mind that most insect repellents don't kill insects. Insects that bite—not insects that sting—are kept away by repellents. Biting insects include mosquitoes, ticks, fleas, chiggers and biting flies. Stinging insects include bees, hornets and wasps.

Insect repellents approved as safe and effective

The American Academy of Pediatrics and Centers for Disease Control and Prevention recommend using an insect repellent product that has been registered by the Environmental Protection Agency (EPA). These products contain ingredients such as DEET, picaridin, oil of lemon eucalyptus or another EPA-registered active ingredient. Use this tool to search for EPA-registered insect repellents.

DEET

Several insect repellents with DEET are approved as safe and effective. The concentration of DEET in a product affects how long the product will be effective. You can choose the lowest concentration to provide protection for the among of time spent outside.

For example, 10% DEET provides protection for about 2 hours, and 30% DEET protects for about 5 hours. A higher concentration works for a longer time, but anything over 50% DEET does not provide longer protection.