Math Is Fun Forum

You are not logged in.

- Topics: Active | Unanswered

Pages: 1

#1 Yesterday 23:41:35

- Jai Ganesh

- Administrator

- Registered: 2005-06-28

- Posts: 53,251

Galvanometer

Galvanometer

Gist

A galvanometer is a highly sensitive electromechanical instrument used to detect and measure small electric currents, primarily in DC circuits. It operates on the principle that a current-carrying coil placed in a magnetic field experiences a torque, causing a pointer to deflect across a scale proportional to the current.

A galvanometer is used to detect the presence, direction, and magnitude of small electric currents in a circuit, acting as a highly sensitive measuring instrument that shows current flow by deflecting a pointer or mirror, often serving as the core component in analog meters like ammeters and voltmeters.

Summary

Galvanometer is the historical name given to a moving coil electric current detector. When a current is passed through a coil in a magnetic field, the coil experiences a torque proportional to the current. If the coil's movement is opposed by a coil spring, then the amount of deflection of a needle attached to the coil may be proportional to the current passing through the coil. Such "meter movements" were at the heart of the moving coil meters such as voltmeters and ammeters until they were largely replaced with solid state meters.

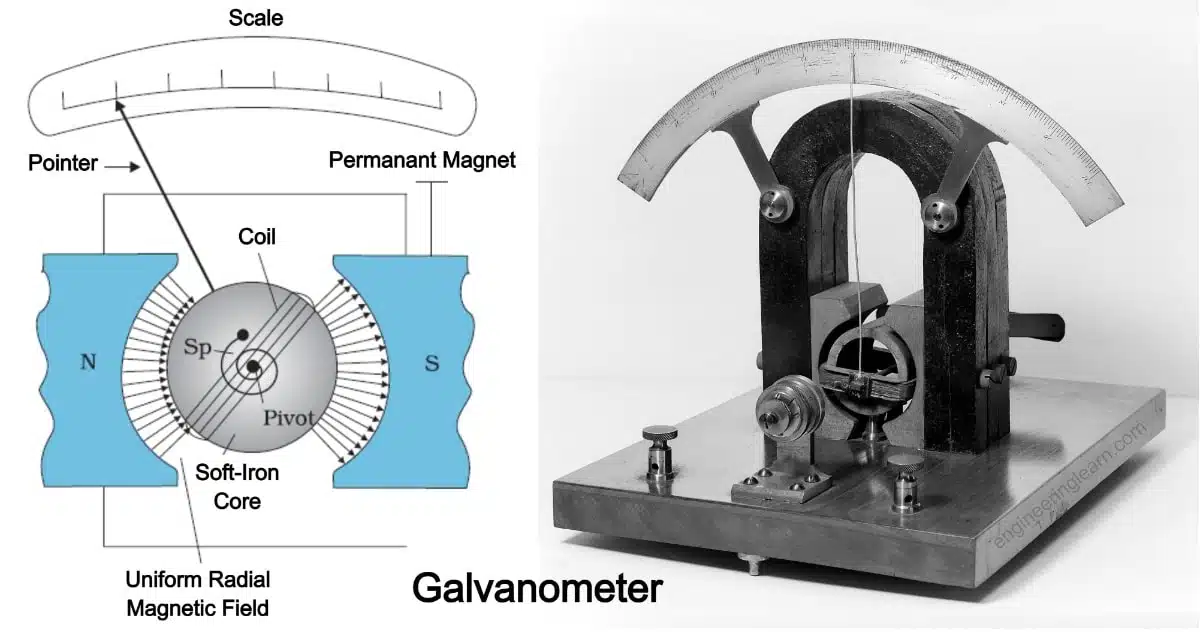

The accuracy of moving coil meters is dependent upon having a uniform and constant magnetic field. The illustration shows one configuration of permanent magnet which was widely used in such meters.

Details

Galvanometers are instruments that measure the electrical potential difference between two points in an electric circuit. The word “galvanometer” comes from the Italian scientist Luigi Galvani, who discovered the principle of bioelectricity in the 18th century.

The earliest galvanometers were simple compasses that were used to detect the presence of an electric current. Over time, these devices became more sophisticated, incorporating coils of wire that could detect very small changes in the electrical current.

In the 19th century, the invention of the tangent galvanometer by William Thomson (later known as Lord Kelvin) revolutionized the field of electricity. This device used a magnet and a coil of wire to measure the strength and direction of an electric current. It was used to develop the first accurate measurements of electrical resistance and to study the behaviour of electric currents in different materials.

Today, galvanometers are used in a wide range of scientific and industrial applications, from measuring the electrical activity of the brain to detecting the presence of magnetic fields. They are also used in a variety of medical devices, such as electrocardiograms (ECGs) and electroencephalograms (EEGs).

The significance of these in modern science cannot be overstated. They have enabled scientists to make accurate measurements of electrical and magnetic fields, paving the way for advances in fields such as physics, chemistry, and engineering. They have also played a crucial role in developing new technologies that have transformed the way we live and work.

Additional Information

A galvanometer is an electromechanical measuring instrument for electric current. Early galvanometers were uncalibrated, but improved versions, called ammeters, were calibrated and could measure the flow of current more precisely. Galvanometers work by deflecting a pointer in response to an electric current flowing through a coil in a constant magnetic field. The mechanism is also used as an actuator in applications such as hard disks.

Galvanometers came from the observation, first noted by Hans Christian Ørsted in 1820, that a magnetic compass's needle deflects when near a wire having electric current. They were the first instruments used to detect and measure small amounts of current. André-Marie Ampère, who gave mathematical expression to Ørsted's discovery, named the instrument after the Italian electricity researcher Luigi Galvani, who in 1791 discovered the principle of the frog galvanoscope – that electric current would make the legs of a dead frog jerk.

Galvanometers have been essential for the development of science and technology in many fields. For example, in the 1800s they enabled long-range communication through submarine cables, such as the earliest transatlantic telegraph cables, and were essential to discovering the electrical activity of the heart and brain, by their fine measurements of current.

Galvanometers have also been used as the display components of other kinds of analog meters (e.g., light meters and VU meters), capturing the outputs of these meters' sensors. Today, the main type of galvanometer still in use is the D'Arsonval/Weston type.

Operation

Modern galvanometers, of the D'Arsonval/Weston type, are constructed with a small pivoting coil of wire, called a spindle, in the field of a permanent magnet. The coil is attached to a thin pointer that traverses a calibrated scale. A tiny torsion spring pulls the coil and pointer to the zero position.

When a direct current (DC) flows through the coil, the coil generates a magnetic field. This field acts against the permanent magnet. The coil twists, pushing against the spring, and moves the pointer. The hand points at a scale indicating the electric current. Careful design of the pole pieces ensures that the magnetic field is uniform so that the angular deflection of the pointer is proportional to the current. A useful meter generally contains a provision for damping the mechanical resonance of the moving coil and pointer, so that the pointer settles quickly to its position without oscillation.

The basic sensitivity of a meter might be, for instance, 100 microamperes full scale (with a voltage drop of, say, 50 millivolts at full current). Such meters are often calibrated to read some other quantity that can be converted to a current of that magnitude. The use of current dividers, often called shunts, allows a meter to be calibrated to measure larger currents. A meter can be calibrated as a DC voltmeter if the resistance of the coil is known by calculating the voltage required to generate a full-scale current. A meter can be configured to read other voltages by putting it in a voltage divider circuit. This is generally done by placing a resistor in series with the meter coil. A meter can be used to read resistance by placing it in series with a known voltage (a battery) and an adjustable resistor. In a preparatory step, the circuit is completed and the resistor adjusted to produce full-scale deflection. When an unknown resistor is placed in series in the circuit the current will be less than full scale and an appropriately calibrated scale can display the value of the previously unknown resistor.

These capabilities to translate different kinds of electric quantities into pointer movements make the galvanometer ideal for turning the output of other sensors that output electricity (in some form or another), into something that can be read by a human.

Because the pointer of the meter is usually a small distance above the scale of the meter, parallax error can occur when the operator attempts to read the scale line that "lines up" with the pointer. To counter this, some meters include a mirror along with the markings of the principal scale. The accuracy of the reading from a mirrored scale is improved by positioning one's head while reading the scale so that the pointer and the reflection of the pointer are aligned; at this point, the operator's eye must be directly above the pointer and any parallax error has been minimized.

Uses

Probably the largest use of galvanometers was of the D'Arsonval/Weston type used in analog meters in electronic equipment. Since the 1980s, galvanometer-type analog meter movements have been displaced by analog-to-digital converters (ADCs) for many uses. A digital panel meter (DPM) contains an ADC and numeric display. The advantages of a digital instrument are higher precision and accuracy, but factors such as power consumption or cost may still favor the application of analog meter movements.

Modern uses

Most modern uses for the galvanometer mechanism are in positioning and control systems. Galvanometer mechanisms are divided into moving magnet and moving coil galvanometers; in addition, they are divided into closed-loop and open-loop - or resonant - types.

Mirror galvanometer systems are used as beam positioning or beam steering elements in laser scanning systems. For example, for material processing with high-power lasers, closed loop mirror galvanometer mechanisms are used with servo control systems. These are typically high power galvanometers and the newest galvanometers designed for beam steering applications can have frequency responses over 10 kHz with appropriate servo technology. Closed-loop mirror galvanometers are also used in similar ways in stereolithography, laser sintering, laser engraving, laser beam welding, laser TVs, laser displays and in imaging applications such as retinal scanning with Optical Coherence Tomography (OCT) and Scanning Laser Ophthalmoscopy (SLO). Almost all of these galvanometers are of the moving magnet type. The closed loop is obtained measuring the position of the rotating axis with an infrared emitter and 2 photodiodes. This feedback is an analog signal.

Open loop, or resonant mirror galvanometers, are mainly used in some types of laser-based bar-code scanners, printing machines, imaging applications, military applications and space systems. Their non-lubricated bearings are especially of interest in applications that require functioning in a high vacuum.

A galvanometer mechanism (center part), used in an automatic exposure unit of an 8 mm film camera, together with a photoresistor (seen in the hole on top of the leftpart).

Moving coil type galvanometer mechanisms (called 'voice coils' by hard disk manufacturers) are used for controlling the head positioning servos in hard disk drives and CD/DVD players, in order to keep mass (and thus access times), as low as possible.

Past uses

A major early use for galvanometers was for finding faults in telecommunications cables. They were superseded in this application late in the 20th century by time-domain reflectometers.

Galvanometer mechanisms were also used to get readings from photoresistors in the metering mechanisms of film cameras.

In analog strip chart recorders such as used in electrocardiographs, electroencephalographs and polygraphs, galvanometer mechanisms were used to position the pen. Strip chart recorders with galvanometer driven pens may have a full-scale frequency response of 100 Hz and several centimeters of deflection.

It appears to me that if one wants to make progress in mathematics, one should study the masters and not the pupils. - Niels Henrik Abel.

Nothing is better than reading and gaining more and more knowledge - Stephen William Hawking.

Offline

Pages: 1