Math Is Fun Forum

You are not logged in.

- Topics: Active | Unanswered

#1 Science HQ » Mandible » Today 01:09:38

- Jai Ganesh

- Replies: 0

Mandible

Gist

In jawed vertebrates, the mandible (from the Latin mandibula, 'for chewing'), lower jaw, or jawbone is a bone that makes up the lower – and typically more mobile – component of the mouth (the upper jaw being known as the maxilla).

Upper jaw (maxilla): Fixed bone that holds your upper teeth and shapes your face. Lower jaw (mandible): The only movable bone in your skull and the strongest facial bone.

The mandible is the largest, strongest, and only movable bone in the human skull, forming the lower jaw, holding the lower teeth, and enabling mastication and speech. It is a U-shaped bone consisting of a horizontal body and two vertical rami that articulate with the temporal bone. It fuses into one bone in early life.

Summary

In jawed vertebrates, the mandible (from the Latin mandibula, 'for chewing'), lower jaw, or jawbone is a bone that makes up the lower – and typically more mobile – component of the mouth (the upper jaw being known as the maxilla).

The jawbone is the skull's only movable, posable bone, sharing joints with the cranium's temporal bones. The mandible hosts the lower teeth (their depth delineated by the alveolar process). Many muscles attach to the bone, which also hosts nerves (some connecting to the teeth) and blood vessels. Amongst other functions, the jawbone is essential for chewing food.

Owing to the Neolithic advent of agriculture (c. 10,000 BCE), human jaws evolved to be smaller. Although it is the strongest bone of the facial skeleton, the mandible tends to deform in old age; it is also subject to fracturing. Surgery allows for the removal of jawbone fragments (or its entirety) as well as regenerative methods. Additionally, the bone is of great forensic significance.

Details:

Introduction

The mandible is the largest and strongest bone of the human skull. It is commonly known as the lower jaw and is located inferior to the maxilla. It is composed of a horseshoe-shaped body which lodges the teeth, and a pair of rami which projects upwards to form a temporomandibular joint.

Structure

The mandible is formed by a body and a pair of rami along with condyloid and coronoid processes.

Body

Body is the anterior portion of the mandible. Body has two surfaces: outer and inner and two borders: upper and lower border. The body ends and the rami begin on either side at the angle of the mandible, also known as the gonial angle.

1. Outer surface is also known as external surface and has following characteristics:

* Mandibular symphysis/ Symphysis menti at midline which joins left and right half of the bone, detected as a subtle ridge in the adult.

* The inferior portion of the ridge divides and encloses a midline depression called the mental protuberance, also known as chin. The edges of the mental protuberance are elevated, forming the mental tubercle.

* Laterally to the ridge and below the incisive teeth is a depression known as the incisive fossa.

* Below the second premolar is the mental foramen, in which the mental nerve and vessels exit.

* The oblique line courses posteriorly from the mental tubercle to the anterior border of the ramus.

2. Inner surface is also known as internal surface and has following features:

* The mylohyoid line is a prominent ridge that runs obliquely downwards and forwards from below the third molar tooth to the median area below the genial tubercles.

* Below the mylohyoid line, the surface is slightly hollowed out to form the sub-mandibular fossa, which lodges the submandibular gland.

* Above the mylohyoid line, there is the sublingual fossa in which the sublingual gland lies.

* The posterior surface of the symphysis menti is marked by four small elevations called the superior and inferior genial tubercles.

3. Upper border (Alveolar border)

It consist of sockets for the teeth.

4. Lower border (Inferior border)

It is also known as base. There is a fossa present at the side of midline known as digastric fossa.

Ramus

The ramus is lateral continuation of the body and is quadrilateral in shape. The coronoid process is the anterosuperior projection of the ramus which is triangular in shape. Whereas posterosuperior projection of ramus is known as condyloid process whose head is covered with fibrocartilage and form a temporomandibular joint. The constricted part below condyloid process is neck. Condyloid and coronoid process are separated by a mandibular notch. It has two surfaces: medial and lateral and four borders: superior, inferior, anterior and posterior.

Ossification

Mandible is the second bone to ossify after clavicle. Each half of the mandible ossifies from only one centre at the sixth week of intrauterine life in the mesenchymal sheath of Meckel's cartilage near the future mental foramen. The first pharyngeal arch, known as the mandibular arch, gives rise to the Meckel cartilage. A fibrous membrane covers the left and right Meckel cartilage at their ventral ends. These two halves eventually fuse via fibrocartilage at the mandibular symphysis. Thus, at birth, the mandible is still composed of two separate bones. Ossification and fusion of the mandibular symphysis occur during the first year of life, resulting in a single bone. The remnant of the mandibular symphysis is a subtle ridge at the midline of the mandible.

The mandible changes throughout the life. In infant and children, the angle of mandible is obtuse with 140 degrees or more making head in line with the body of the mandible. Whereas in adult the angle decreases to about 110-120 degree making ramus almost vertical.

Additional Information

Mandible, in anatomy, is the movable lower jaw, consisting of a single bone or of completely fused bones in humans and other mammals. In birds, the mandible constitutes either the upper or the lower segment of the bill, and in invertebrates it is any of the various mouthparts that holds or bites food materials, including either of the paired mouth appendages of an arthropod that form the biting jaws.

In humans, the mandible is the only mobile bone of the skull (other than the tiny bones of the middle ear). It is attached to muscles involved in chewing and other mouth movements and functions by moving in opposition to the maxilla (upper jaw); together, the two parts are used for biting, chewing, and handling food. The structure of the human mandible resembles a more or less horizontal arch, which holds the teeth and contains blood vessels and nerves. At the rear of the mandible, two more or less vertical portions (rami) form movable hinge joints, one on each side of the head, articulating with the glenoid cavity of the temporal bone of the skull to form the temporomandibular joints. The rami also provide attachment for muscles important in chewing. The centre front of the arch is thickened and buttressed to form the chin, a development unique to humans and some of their recent ancestors; the great apes and other animals lack chins. In the human fetus and infant, the maxilla and the mandible are each separated at the midline; the halves fuse a few months after birth.

Invertebrate jaw and mouthpart structures vary markedly. For example, in the primitive bloodsucking flies (e.g., the horse fly [Tabanus]), the mandibles and maxillae form serrated blades that cut through the skin and blood vessels of the host animal. In the mosquito (Culicidae), the mandibles and associated structures have become exceedingly slender stylets that form a fine bundle used for piercing skin and entering blood vessels. In the housefly (Musca domestica), the mandibles and maxillae have been lost; the tonguelike labium alone remains and serves for feeding on exposed surfaces. Among crustaceans, processes at the base of the antennae may help the mandibles push food into the mouth. The paired mandibles of a nauplius (the most widespread and typical crustacean larva to emerge from the egg) each have two branches, one with a chewing lobe and the other with a compressing lobe at the base; the mandibles may also be used for swimming. In the adult crustacean, each mandible loses one of the branches, sometimes retaining the other as a palp, and the base may develop into a powerful jaw. An alternative development is found in some of the blood-sucking parasites, in which the mandibles form needlelike stylets for piercing a host.

In humans, the most common conditions that affect the function of the mandible are temporomandibular joint disorders (TMDs), of which there are about 30 different types. TMDs may have an impact on the function of the jaw muscles and the temporomandibular joints and may irritate associated nerves. The cause of a TMD is often unclear; factors that may play a role include osteoarthritis and physical trauma. Symptoms vary but may include dizziness, earache, facial pain, headache, jaw tenderness, and reduced jaw mobility. Many TMDs resolve on their own; otherwise, treatment ranges from simple dietary changes (e.g., eating only soft foods) to physical therapy or medication to the use of intraoral appliances (devices fitted over the teeth) to complex surgical or dental procedures.

#2 Re: This is Cool » Miscellany » 2026-01-22 22:59:01

2477) Photosysthesis

Gist

Photosynthesis is the vital process where plants, algae, and some bacteria use sunlight, water, and carbon dioxide to create their own food (glucose/sugars) and release oxygen, converting light energy into stored chemical energy, forming the base of most food webs and producing atmospheric oxygen. It involves light-dependent reactions (capturing energy in ATP/NADPH using chlorophyll) and light-independent reactions (Calvin Cycle) that use this energy to build sugars, occurring in chloroplasts.

Photosynthesis is the process where plants, algae, and some bacteria use sunlight, water, and carbon dioxide to create their own food (glucose/sugar) and release oxygen as a byproduct, converting light energy into stored chemical energy. This vital process, primarily occurring in chloroplasts, provides the energy and oxygen necessary for most life on Earth.

Summary

Photosynthesis is a system of biological processes by which photopigment-bearing autotrophic organisms, such as most plants, algae and cyanobacteria, convert light energy — typically from sunlight — into the chemical energy necessary to fuel their metabolism. The term photosynthesis usually refers to oxygenic photosynthesis, a process that releases oxygen as a byproduct of water splitting. Photosynthetic organisms store the converted chemical energy within the bonds of intracellular organic compounds (complex compounds containing carbon), typically carbohydrates like sugars (mainly glucose, fructose and sucrose), starches, phytoglycogen and cellulose. When needing to use this stored energy, an organism's cells then metabolize the organic compounds through cellular respiration. Photosynthesis plays a critical role in producing and maintaining the oxygen content of the Earth's atmosphere, and it supplies most of the biological energy necessary for complex life on Earth.

Some organisms also perform anoxygenic photosynthesis, which does not produce oxygen. Some bacteria (e.g. purple bacteria) use bacteriochlorophyll to split hydrogen sulfide as a reductant instead of water, releasing sulfur instead of oxygen, which was a dominant form of photosynthesis in the euxinic Canfield oceans during the Boring Billion. Archaea such as Halobacterium also perform a type of non-carbon-fixing anoxygenic photosynthesis, where the simpler photopigment retinal and its microbial rhodopsin derivatives are used to absorb green light and produce a proton (hydron) gradient across the cell membrane, and the subsequent ion movement powers transmembrane proton pumps to directly synthesize adenosine triphosphate (ATP), the "energy currency" of cells. Such archaeal photosynthesis might have been the earliest form of photosynthesis that evolved on Earth, as far back as the Paleoarchean, preceding that of cyanobacteria (see Purple Earth hypothesis).

While the details may differ between species, the process always begins when light energy is absorbed by the reaction centers, proteins that contain photosynthetic pigments or chromophores. In plants, these pigments are chlorophylls (a porphyrin derivative that absorbs the red and blue spectra of light, thus reflecting green) held inside chloroplasts, abundant in leaf cells. In cyanobacteria, they are embedded in the plasma membrane. In these light-dependent reactions, some energy is used to strip electrons from suitable substances, such as water, producing oxygen gas. The hydrogen freed by the splitting of water is used in the creation of two important molecules that participate in energetic processes: reduced nicotinamide adenine dinucleotide phosphate (NADPH) and ATP.

In plants, algae, and cyanobacteria, sugars are synthesized by a subsequent sequence of light-independent reactions called the Calvin cycle. In this process, atmospheric carbon dioxide is incorporated into already existing organic compounds, such as ribulose bisphosphate (RuBP). Using the ATP and NADPH produced by the light-dependent reactions, the resulting compounds are then reduced and removed to form further carbohydrates, such as glucose. In other bacteria, different mechanisms like the reverse Krebs cycle are used to achieve the same end.

The first photosynthetic organisms probably evolved early in the evolutionary history of life using reducing agents such as hydrogen or hydrogen sulfide, rather than water, as sources of electrons. Cyanobacteria appeared later; the excess oxygen they produced contributed directly to the oxygenation of the Earth, which rendered the evolution of complex life possible. The average rate of energy captured by global photosynthesis is approximately 130 terawatts, which is about eight times the total power consumption of human civilization. Photosynthetic organisms also convert around 100–115 billion tons (91–104 Pg petagrams, or billions of metric tons), of carbon into biomass per year. Photosynthesis was discovered in 1779 by Jan Ingenhousz who showed that plants need light, not just soil and water.

Details

Photosynthesis is the process by which green plants and certain other organisms transform light energy into chemical energy. During photosynthesis in green plants, light energy is captured and used to convert water, carbon dioxide, and minerals into oxygen and energy-rich organic compounds.

Importance of photosynthesis

It would be impossible to overestimate the importance of photosynthesis in the maintenance of life on Earth. The Great Oxidation Event, which began about 2.4 billion years ago and was largely driven by the photosynthetic cyanobacteria, raised atmospheric oxygen to nearly 1 percent of present levels over a span of 600 million years, paving the way for the evolution of most forms of multicellular life. Photosynthesis completely transformed Earth’s environment and biosphere. The life-giving process continues to sustain biodiversity since autotrophs are foundational to nearly every food web on the planet. If photosynthesis ceased, there would soon be little food or other organic matter on Earth. Most organisms would disappear, and in time Earth’s atmosphere would become nearly devoid of gaseous oxygen. The only organisms able to exist under such conditions would be the chemosynthetic bacteria, which can utilize the chemical energy of certain inorganic compounds and thus are not dependent on the conversion of light energy.

Energy produced by photosynthesis carried out by plants millions of years ago is responsible for the fossil fuels (i.e., coal, oil, and natural gas) that power industrial society. In past ages, green plants and small organisms that fed on plants increased faster than they were consumed, and their remains were deposited in Earth’s crust by sedimentation and other geological processes. There, protected from oxidation, these organic remains were slowly converted to fossil fuels. These fuels not only provide much of the energy used in factories, homes, and transportation but also serve as the raw material for plastics and other synthetic products. Unfortunately, modern civilization is using up in a few centuries the excess of photosynthetic production accumulated over millions of years. Consequently, the carbon dioxide that has been removed from the air to make carbohydrates in photosynthesis over millions of years is being returned at an incredibly rapid rate. The carbon dioxide concentration in Earth’s atmosphere is rising the fastest it ever has in Earth’s history, and this phenomenon—known as global warming—is expected to have major implications on Earth’s climate.

Evolution of the process

Although life and the quality of the atmosphere today depend on photosynthesis, it is likely that green plants evolved long after the first living cells. When Earth was young, electrical storms and solar radiation probably provided the energy for the synthesis of complex molecules from abundant simpler ones, such as water, ammonia, and methane. The first living cells probably evolved from these complex molecules. For example, the accidental joining (condensation) of the amino acid glycine and the fatty acid acetate may have formed complex organic molecules known as porphyrins. These molecules, in turn, may have evolved further into colored molecules called pigments—e.g., chlorophylls of green plants, bacteriochlorophyll of photosynthetic bacteria, hemin (the red pigment of blood), and cytochromes, a group of pigment molecules essential in both photosynthesis and cellular respiration.

Primitive colored cells then had to evolve mechanisms for using the light energy absorbed by their pigments. At first, the energy may have been used immediately to initiate reactions useful to the cell. As the process for using light energy continued to evolve, however, a larger part of the absorbed light energy probably was stored as chemical energy, to be used to maintain life. Green plants, with their ability to use light energy to convert carbon dioxide and water to carbohydrates and oxygen, are the culmination of this evolutionary process.

The first oxygenic (oxygen-producing) cells probably were the cyanobacteria (blue-green algae), which appeared about two billion to three billion years ago. These microscopic organisms are believed to have greatly increased the oxygen content of the atmosphere, making possible the development of aerobic (oxygen-using) organisms. Cyanophytes are prokaryotic cells; that is, they contain no distinct membrane-enclosed subcellular particles (organelles), such as nuclei and chloroplasts. Green plants, by contrast, are composed of eukaryotic cells, in which the photosynthetic apparatus is contained within membrane-bound chloroplasts. The complete genome sequences of cyanobacteria and higher plants provide evidence that the first photosynthetic eukaryotes were likely the red algae that developed when nonphotosynthetic eukaryotic cells engulfed cyanobacteria. Within the host cells, these cyanobacteria evolved into chloroplasts.

There are a number of photosynthetic bacteria that are not oxygenic (e.g., the sulfur bacteria previously discussed). The evolutionary pathway that led to these bacteria diverged from the one that resulted in oxygenic organisms. In addition to the absence of oxygen production, nonoxygenic photosynthesis differs from oxygenic photosynthesis in two other ways: light of longer wavelengths is absorbed and used by pigments called bacteriochlorophylls, and reduced compounds other than water (such as hydrogen sulfide or organic molecules) provide the electrons needed for the reduction of carbon dioxide.

Additional Information

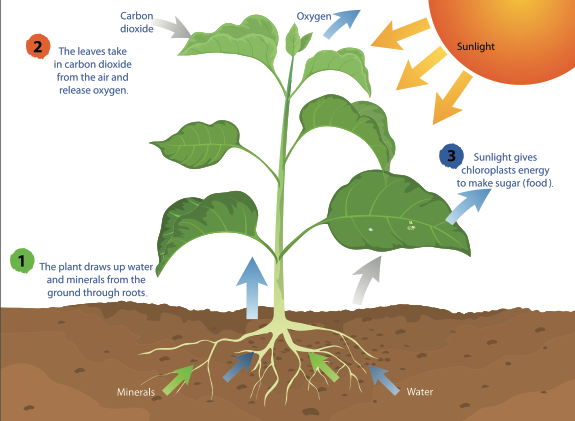

Photosynthesis is the process by which plants use sunlight, water, and carbon dioxide to create oxygen and energy in the form of sugar.

Most life on Earth depends on photosynthesis.The process is carried out by plants, algae, and some types of bacteria, which capture energy from sunlight to produce oxygen (O2) and chemical energy stored in glucose (a sugar). Herbivores then obtain this energy by eating plants, and carnivores obtain it by eating herbivores.

The process

During photosynthesis, plants take in carbon dioxide (CO2) and water (H2O) from the air and soil. Within the plant cell, the water is oxidized, meaning it loses electrons, while the carbon dioxide is reduced, meaning it gains electrons. This transforms the water into oxygen and the carbon dioxide into glucose. The plant then releases the oxygen back into the air, and stores energy within the glucose molecules.

Chlorophyll

Inside the plant cell are small organelles called chloroplasts, which store the energy of sunlight. Within the thylakoid membranes of the chloroplast is a light-absorbing pigment called chlorophyll, which is responsible for giving the plant its green color. During photosynthesis, chlorophyll absorbs energy from blue- and red-light waves, and reflects green-light waves, making the plant appear green.

Light-dependent Reactions vs. Light-independent Reactions

While there are many steps behind the process of photosynthesis, it can be broken down into two major stages: light-dependent reactions and light-independent reactions. The light-dependent reaction takes place within the thylakoid membrane and requires a steady stream of sunlight, hence the name light-dependent reaction. The chlorophyll absorbs energy from the light waves, which is converted into chemical energy in the form of the molecules ATP and NADPH. The light-independent stage, also known as the Calvin cycle, takes place in the stroma, the space between the thylakoid membranes and the chloroplast membranes, and does not require light, hence the name light-independent reaction. During this stage, energy from the ATP and NADPH molecules is used to assemble carbohydrate molecules, like glucose, from carbon dioxide.

C3 and C4 Photosynthesis

Not all forms of photosynthesis are created equal, however. There are different types of photosynthesis, including C3 photosynthesis and C4 photosynthesis. C3 photosynthesis is used by the majority of plants. It involves producing a three-carbon compound called 3-phosphoglyceric acid during the Calvin Cycle, which goes on to become glucose. C4 photosynthesis, on the other hand, produces a four-carbon intermediate compound, which splits into carbon dioxide and a three-carbon compound during the Calvin Cycle. A benefit of C4 photosynthesis is that by producing higher levels of carbon, it allows plants to thrive in environments without much light or water.

#3 This is Cool » Monaco » 2026-01-22 20:35:29

- Jai Ganesh

- Replies: 0

Monaco

Gist

Monaco is famous for its extreme wealth, luxury lifestyle, tax haven status (no income tax for residents), glamorous casinos (like the Monte Carlo Casino), yacht-filled harbors, and high-profile events like the Formula 1 Monaco Grand Prix, attracting the world's rich and famous to its French Riviera location, says TATA AIG, Wikipedia, and Study.com. As the world's second-smallest country, it's a major banking center, a hub for high-end tourism, and home to the ruling Grimaldi family, blending historic charm with modern sophistication.

The Monaco permanent residency card ("Carte de Sejour") allow applicants to live in Monaco indefinitely. Permanent residency is granted on the basis of demonstrating proof of accommodation and proof of financial self-sufficiency.

Summary

Monaco, officially the Principality of Monaco, is a sovereign city-state and microstate in Western Europe. Situated on the French Riviera, it is a semi-enclave bordered by France to the north, east, and west, with the Mediterranean Sea to the south; the Italian region of Liguria is about 15 km (9.3 mi) east. With a population of 38,423 living in an area of 2.08 sq km (0.80 sq mi), Monaco is the second smallest sovereign state in the world, after Vatican City, as well as the most densely populated. It also has the world's shortest national coastline of any non-landlocked nation, at 3.83 km (2.38 mi). Fewer than 10,000 of its residents are Monégasque nationals. Although French is the official language of Monaco, Italian and Monégasque are also widely spoken and understood.

Monaco is governed under a form of semi-constitutional monarchy, with Prince Albert II as head of state, who holds substantial political powers. The prime minister, who is the head of government, can be either a Monégasque or French citizen; the monarch consults with the Government of France before an appointment. Key members of the judiciary are detached French magistrates. The House of Grimaldi has ruled Monaco, with brief interruptions, since 1297. The state's sovereignty was officially recognised by the Franco-Monégasque Treaty of 1861, with Monaco becoming a full United Nations voting member in 1993. Despite Monaco's independence and separate foreign policy, its defence is the responsibility of France, notwithstanding two small military units.

Monaco is recognised as one of the wealthiest and most expensive places in the world. Its economic development was spurred in the late 19th century with the opening of the state's first casino, the Monte Carlo Casino, and a rail connection to Paris. The country's mild climate, scenery, and gambling facilities contributed to its status as a tourist destination and recreation centre for the wealthy. Monaco has become a major banking centre and sought to diversify into the services sector and small, high-value-added, non-polluting industries. Monaco is a tax haven; it has no personal income tax (except for French citizens) and low business taxes. Over 30% of residents are millionaires, with real estate prices reaching €100,000 ($116,374) per square metre in 2018. Monaco is a global hub of money laundering, and in June 2024 the Financial Action Task Force placed Monaco under increased monitoring to combat money laundering and terrorist financing.

Monaco is among the 46 Member States which constitute the Council of Europe. It is not part of the European Union (EU), but participates in certain EU policies, including customs and border controls. Through its relationship with France, Monaco uses the euro as its sole currency. Monaco joined the Council of Europe in 2004 and is a member of the Organisation internationale de la Francophonie (OIF). It hosts the annual motor race, the Monaco Grand Prix, one of the original Grands Prix of Formula One. The local motorsports association gives its name to the Monte Carlo Rally, hosted in January in the French Alps. The principality has a club football team, AS Monaco, which competes in French Ligue 1 and has been French champions on multiple occasions, as well as a basketball team, which plays in the EuroLeague. Monaco is a centre of marine conservation and research, being home to one of the world's first protected marine habitats, an Oceanographic Museum, and the International Atomic Energy Agency Marine Environment Laboratories, the only marine laboratory in the UN system.

Details

Monaco is a sovereign principality located along the Mediterranean Sea in the midst of the resort area of the Côte d’Azur (French Riviera). The city of Nice, France, lies 9 miles (15 km) to the west, the Italian border 5 miles (8 km) to the east. Monaco’s tiny territory occupies a set of densely clustered hills and a headland that looks southward over the Mediterranean. Many unusual features, however, have made Monaco among the most luxurious tourist resorts in the world and have given it a fame far exceeding its size.

Many visitors to Monaco alternate their hours between its beaches and boating facilities, its international sports-car races, and its world-famous Place du Casino, the gambling centre in the Monte-Carlo section that made Monte-Carlo an international byword for the extravagant display and reckless dispersal of wealth. The country has a mild Mediterranean climate with annual temperatures averaging 61 °F (16 °C) and with only about 60 days of rainfall. Monthly average temperatures range from 50 °F (10 °C) in January to 75 °F (24 °C) in August.

Evidences of Stone Age settlements in Monaco are preserved in the principality’s Museum of Prehistoric Anthropology. In ancient times the headland was known to the Phoenicians, Greeks, Carthaginians, and Romans. In 1191 the Genoese took possession of it, and in 1297 the long reign of the Grimaldi family began. The Grimaldis allied themselves with France except for the period from 1524 to 1641, when they were under the protection of Spain. In 1793 they were dispossessed by the French Revolutionary regime, and Monaco was annexed to France. With the fall of Napoleon I, however, the Grimaldis returned; the Congress of Vienna (1815) put Monaco under the protection of Sardinia. The principality lost the neighboring towns of Menton and Roquebrune in 1848 and finally ceded them to France under the terms of the Franco-Monegasque treaty of 1861. The treaty did restore Monaco’s independence, however, and in 1865 a customs union was established between the two countries. Another treaty that was made with France, in 1918, contained a clause providing that, in the event that the Grimaldi dynasty should become extinct, Monaco would become an autonomous state under French protection. A revision to the constitution in 2002 added females and their legitimate children to the line of succession. In 1997 the Grimaldi family commemorated 700 years of rule, and in 1999 Prince Rainier III marked 50 years on the throne. Upon his death in April 2005, he was succeeded by his son, Albert; Albert formally assumed the throne on July 12, 2005. The principality joined the United Nations in 1993. Though not a member of the European Union (EU), Monaco phased out the French franc for the single European currency of the euro by 2002.

Monaco’s refusal to impose income taxes on its residents and on international businesses that have established headquarters in the principality led to a severe crisis with France in 1962. A compromise was reached by which French citizens with less than five years residence in Monaco were taxed at French rates and taxes were imposed on Monegasque companies doing more than 25 percent of their business outside the principality. In the early 21st century, some European nations criticized Monaco’s loose banking regulations, claiming that the principality sheltered tax evaders and money launderers. In 2002 the Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD) added Monaco to its “blacklist” of uncooperative tax havens. The principality was removed from the blacklist in 2009 after committing to OECD transparency standards.

Monaco’s constitution of 1911 provided for an elected National Council, but in 1959 Prince Rainier III suspended part of the constitution and dissolved the National Council because of a disagreement over the budget. In 1961 he appointed instead a national assembly. The aforementioned crisis of 1962 with France led him to restore the National Council and to grant a new, liberal constitution. The council comprises 18 members, elected by universal suffrage for a term of five years. Government is carried on by a minister of state (who must be a French citizen) and three state councillors acting under the authority of the prince, who is the official chief of state. Legislative power is shared by the prince and the National Council. Since 1819 the judicial system has been based on that of France; since 1962 the highest judicial authority has been the Supreme Tribunal.

A substantial portion of the government’s revenues comes from taxes on commercial transactions; additional revenue is drawn from franchises on radio, television, and the casino, from state-operated monopolies on tobacco and postage stamps, from sales taxes, and from the taxes imposed since 1962.

Monaco’s chief industry is tourism, and its facilities make it one of Europe’s most luxurious resorts. Once a winter attraction, it now draws summer visitors as well to its beaches and expanded mooring facilities. Business conferences are especially important. The social life of Monte-Carlo revolves around the Place du Casino. The casino was built in 1861, and in 1967 its operations were taken over by the principality. Banking and finance and real estate are other important components of the diverse services sector.

More than one-fourth of Monaco’s population is composed of French citizens, and a smaller but significant number are Italian, Swiss, and Belgian. Only about one-fifth of the population claims Monegasque descent. Most of the people are Roman Catholics. The official language is French.

The four sections, or quartiers, of Monaco are the town of Monaco, or “the Rock,” a headland jutting into the sea on which the old town is located; La Condamine, the business district on the west of the bay, with its natural harbor; Monte-Carlo, including the gambling casino; and the newer zone of Fontvieille, in which various light industries have developed.

In Monaco are the Roman Catholic cathedral, the prince’s Genoese and Renaissance palace, and the Oceanographic Museum of Monaco, built in 1910. The casino itself contains a theater designed by the 19th-century French architect Charles Garnier, which is the home of the Opéra de Monte Carlo. During the 1920s many of the works of the famous Ballets Russes of Serge Diaghilev were given their premieres there. There is also a Monte-Carlo national orchestra. The best known of the automobile events held in the principality are the Monte-Carlo Rally and the Grand Prix de Monaco.

Additional Information

Monaco is the second-smallest independent state in the world. It is a playground for tourists and a haven for the wealthy, the former drawn by its climate and the beauty of its setting and the latter by its advantageous tax regime.

The country - a constitutional monarchy - is surrounded on three sides by France.

Tourism is a major earner for the economy. The country is also a major banking centre and closely guards the privacy of its clients. Monaco does not levy income tax on its residents.

Its sovereignty was officially recognised by the Franco-Monegasque Treaty of 1861, with Monaco becoming a full United Nations voting member in 1993.

#4 Science HQ » Dura Mater » 2026-01-22 18:44:20

- Jai Ganesh

- Replies: 0

Dura Mater

Gist

The tough outer layer of tissue that covers and protects the brain and spinal cord and is closest to the skull.

The meningeal layer of the dura mater creates several dural folds that divide the cranial cavity into freely communicating spaces. The function of the dural folds is to limit the rotational displacement of the brain. The folds include the following: The falx cerebri is a meningeal projection of dura in the brain.

Dura is the thick outer most layer of the 3 meninges. The thick fibrous dura surrounds, supports and protects the central nervous system (brain and spinal cord). In the cranium the dura forms folds to form partitions of the cranial cavity, and separates in places to form dural venous sinuses.

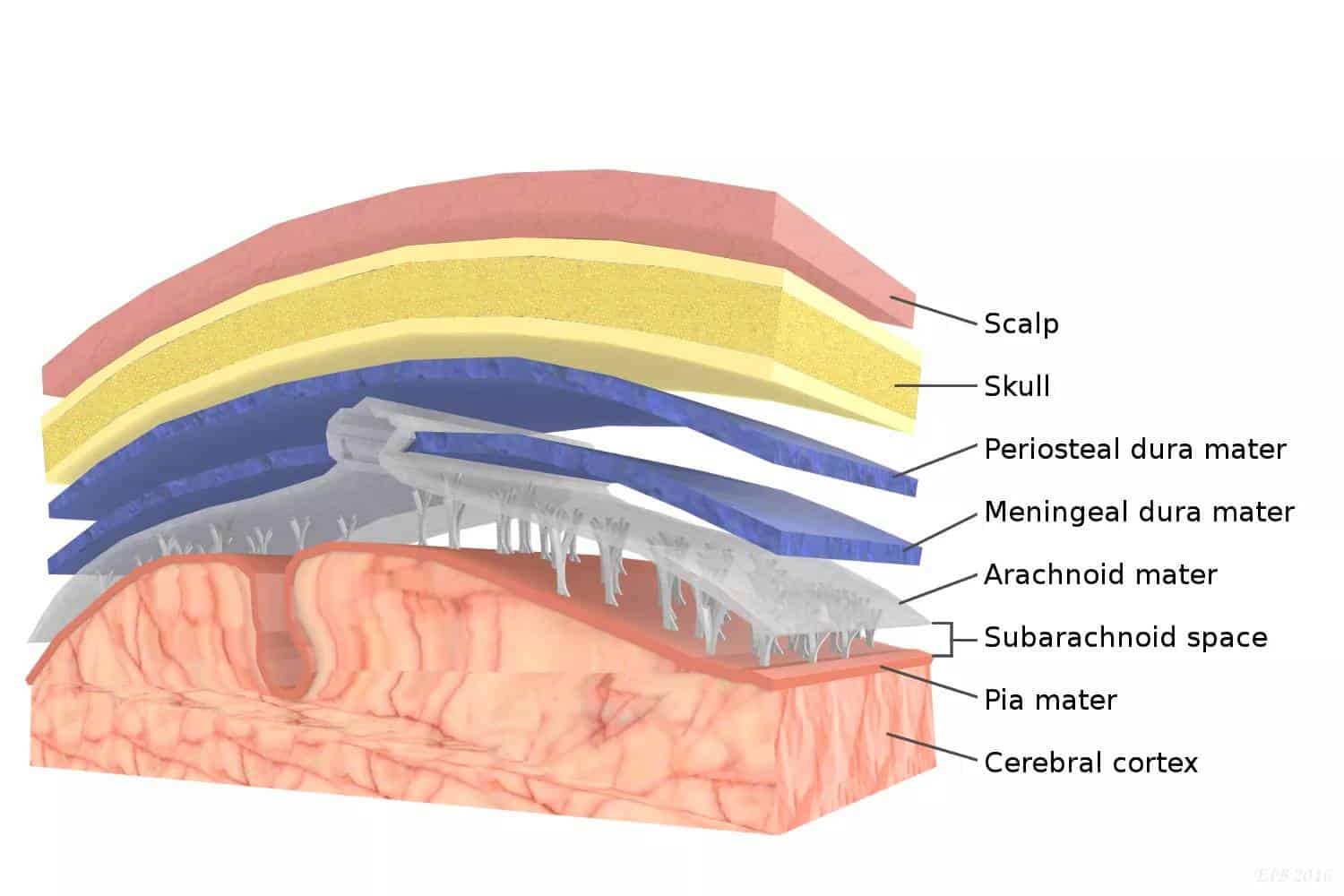

Summary

The dura mater (or just dura) is the outermost of the three meningeal membranes. The dura mater has two layers, an outer periosteal layer closely adhered to the neurocranium, and an inner meningeal layer known as the dural border cell layer. The two dural layers are for the most part fused together forming a thick fibrous tissue membrane that covers the brain and the vertebrae of the spinal column. But the layers are separated at the dural venous sinuses to allow blood to drain from the brain. The dura covers the arachnoid mater and the pia mater, the other two meninges, in protecting the central nervous system.

At major boundaries of brain regions such as the longitudinal fissure between the hemispheres, and the tentorium cerebelli between the posterior brain and the cerebellum the dura separates, folds and invaginates to make the divisions. These folds are known as dural folds, or reflections.

The dura mater is primarily derived from neural crest cells, with postnatal contributions from the paraxial mesoderm.

Details

The meninges are three layers of connective tissue that surround, support and protect the central nervous system (brain and spinal cord). From superficial to deep these layers are named the dura, arachnoid and pia. The dura mater is a thick, tough, fibrous membrane. It receives blood and nerve supply from the meningeal arteries, veins and nerves.

Cranial dura mater

In the cranium, the dura consists of two layers; an outer periosteal dura and an inner meningeal dura. The periosteal dura is closely attached to the internal surface of the skull bones while the inner meningeal dura is continuous with the dura of the spinal cord. The periosteal dura and meningeal dura are tightly fused together, except in a few places where they separate to form the dural venous sinuses; spaces that collect venous blood from the large veins of the brain. The dural venous sinuses are named as follows; superior sagittal sinus, inferior sagittal sinus, straight sinus, occipital sinus, transverse sinus, sigmoid sinus, marginal sinus, superior petrosal sinus, inferior petrosal sinus, petrosquamous sinus, cavernous sinus, sphenoparietal sinus, intercavernous sinus. The straight, occipital, transverse and superior sagittal sinuses all meet at the confluence of the sinuses. Arachnoid granulations, small tufts of arachnoid, protrude through the dura mater into the dural venous sinuses. They are the site of cerebrospinal fluid absorption into dural venous sinuses. Another feature of cranial dura are the dural folds. These are reflections of the inner meningeal dura which divide the cranium into separate compartments. The four dural folds are the falx cerebri, tentorium cerebelli, falx cerebelli, diaphragma sellae; in brief, they separate the cerebral and cerebellar hemispheres into divisions.

Spinal dura mater

In the spinal cord, only one layer of dura mater is found. Unlike in the cranium, the dura is not closely integrated with the overlying bones. Instead, a space exists between the dura and the vertebral bones known as the epidural space. The inferior aspect of the spinal dural sac is anchored to the coccyx by a thin connective tissue strand called the filum terminale.

Innervation

The innervation of the cranial dura mater is primarily sourced from the trigeminal (CN V) and vagus CN X) nerves, as well as spinal nerves C2/C3.

Trigeminal nerve

Several branches of the trigeminal nerve supply the dura mater:

* The tentorial branch of the ophthalmic nerve (CN V1), also known as the recurrent meningeal branch, supplies much of the supratentorial dura mater (i.e., posterior half of the falx cerebri, calvarial dura and superior surface of the tentorium cerebelli).

* The meningeal branch of the anterior ethmoidal nerve (branch of the nasociliary nerve (ophthalmic nerve)) supplies the central region of the anterior cranial fossa as well as anterior parts of the falx cerebri.

* The meningeal branch of the maxillary nerve (CN V2) provides innervation to the posterior region of the anterior cranial fossa as well as the anterior portion of the middle cranial fossa.

* The meningeal branch of the mandibular nerve (CN V3) supplies the posterolateral parts of the middle cranial fossa, before extending anteriorly to the lateral region of the anterior cranial fossa.

Vagus nerve

The posterior and lateral regions of the posterior cranial fossa and inferior surface of the tentorium cerebelli are all primarily innervated by the meningeal branch of the vagus nerve (which arises from its superior ganglion).

Spinal nerves C2/C3

The central region of the posterior cranial fossa, around the foramen magnum, receives innervation from sensory nerve fibers whose cell bodies are located in the spinal ganglia of spinal nerves C2/C3. The nerves may present as ascending branches of the meningeal branch of these spinal nerves which ascend the vertebral canal into the cranial cavity, via the foramen magnum. Alternatively, communicating branches of spinal nerves C2/C3 may pass to the hypoglossal nerve (CN XII), entering the cranial cavity via the meningeal branch of the hypoglossal nerve (via the hypoglossal canal). Some references occasionally also describe meningeal branches derived from the facial (CN VII) and glossopharyngeal (CN IX) nerves as supplying the posterior cranial fossa, however this remains debated.

Spinal dura

The innervation of the spinal dura mater is derived from a meningeal branch of each spinal nerve. It arises near the division of the spinal nerve into anterior and posterior rami, close to the gray/white rami communicating branches, before coursing through the intervertebral foramen into the vertebral canal.

Additional Information

The brain is an important part of the human body, as it performs vital functions and controls almost all bodily functions. It is protected by a strong framework of bones, called the skull. Besides this bony structure, it is also protected against several kinds of injuries or head traumas by the meninges, which are three-layered membranous structures that help protect the brain parts from damage.

The outermost layer of the meninges is the dura mater. The other two layers are collectively known as the leptomeninges and consist of the arachnoid mater (middle layer) and the pia mater (innermost layer). The dura mater is frequently known as the dura.

The dura protects its vital underlying components with a strong fibrous protective covering. In aspects of compressive impacts due to mass lesions and related edema, the compartmentalization of the brain through the help of dural reflections is especially important. The connection of the dural layers to each other, and the underlying leptomeninges and calvarium, has a huge impact on scientists’ knowledge of the impacts of intracranial injury.

Summary:

* The meninges safeguard the spinal cord and brain from tissue injury and assist the framework of the blood vessels

* Dura mater is on the outermost end of the meninges, situated directly beneath the skull and the bones of the vertebral column

* The dura mater is made up of two layers of connective tissue: the periosteal layer and the meningeal layer

* The periosteal layer lines the inner surface of the cranium’s bones. The periosteum is a dense fibrous membrane that covers the surface areas of bones

* The meningeal layer is found deep within the periosteal layer

* The dura mater has a vascular supply of its own

* The dura mater’s meningeal layer bends towards the inner direction of itself to form 4 structural forms, called the dural reflections

* The 4 dural reflections are: Diaphagma sellae, Falx cerebri, Tentorium cerebelli, and Falx cerebelli

* Dura mater encircles and continues to support the large venous channels (called dural sinuses) that help in carrying the blood from the brain to the heart.

* Haemorrhage, meningitis, and meningiomas are some complications involving the dura mater.

#5 Re: Dark Discussions at Cafe Infinity » crème de la crème » 2026-01-22 18:06:17

2417) Donald Glaser

Gist:

Life

Donald Glaser was born in Cleveland, Ohio to Russian immigrants. His father was a businessman. After first studying at Case School of Applied Science in Cleveland, he later received his PhD in physics from California Institute of Technology, Pasadena, in 1949. He then moved to the University of Michigan in Ann Arbor, where he carried out the research that led to his Nobel Prize, before moving to the University of California, Berkeley, in 1959. Beginning in the 1960s, Glaser devoted himself to molecular biology. He was married twice and had two children from his first marriage.

Work

Our ability to study the smallest components of our world took a giant leap forward when C.T.R. Wilson invented the cloud chamber, where the trails of charged particles can be observed. Donald Glaser's invention of the bubble chamber in 1952 made it possible to study particles with higher energies. When charged particles rush forward through the chamber filled with a liquid at near-boiling point, they ionize atoms they pass by. When the pressure inside the chamber is then reduced, bubbles form around these charged atoms. The particles' tracks can then be photographed and analyzed.

Summary

Donald A. Glaser (born September 21, 1926, Cleveland, Ohio, U.S.—died February 28, 2013, Berkeley, California) was an American physicist and recipient of the 1960 Nobel Prize for Physics for his invention (1952) and development of the bubble chamber, a research instrument used in high-energy physics laboratories to observe the behaviour of subatomic particles.

After graduating from Case Institute of Technology, Cleveland, in 1946, Glaser attended the California Institute of Technology, Pasadena, where he received a Ph.D. in physics and mathematics in 1950. He then began teaching at the University of Michigan, where he became a professor in 1957.

Glaser conducted research with Nobelist Carl Anderson, who was using cloud chambers to study cosmic rays. Glaser, recognizing that cloud chambers had a number of limitations, created a bubble chamber to learn about the pathways of subatomic particles. Because of the relatively high density of the bubble-chamber liquid (as opposed to the vapour that filled cloud chambers), collisions producing rare reactions were more frequent and were observable in finer detail. New collisions could be recorded every few seconds when the chamber was exposed to bursts of high-speed particles from particle accelerators. As a result, physicists were able to discover the existence of a host of new particles, notably quarks. At the age of 34, Glaser became one of the youngest scientists ever to be awarded a Nobel Prize.

In 1959 Glaser joined the staff of the University of California, Berkeley, where he became a professor of physics and molecular biology in 1964. In 1971 he cofounded the Cetus Corp., a biotechnology company that developed interleukin-2 and interferon for cancer therapy. The firm was sold (1991) to Chiron Corp., which was later acquired by Novartis. In the 1980s Glaser turned to the field of neurobiology and conducted experiments on vision and how it is processed by the human brain.

Details

Donald Arthur Glaser (September 21, 1926 – February 28, 2013) was an American physicist and biologist who received the Nobel Prize in Physics in 1960 for his invention of the bubble chamber.

Personal life

Donald Arthur Glaser was born on September 21, 1926, in Cleveland, Ohio, to Russian Jewish immigrants, Lena and William J. Glaser, a businessman. He enjoyed music and played the piano, violin, and viola. He went to Cleveland Heights High School, where he became interested in physics as a means to understand the physical world. He died in his sleep at the age of 86 on February 28, 2013, in Berkeley, California.

Education and career

Glaser attended Case School of Applied Science (now Case Western Reserve University), where he completed his Bachelor of Science degree in physics and mathematics in 1946. During the course of his education there, he became especially interested in particle physics. He played viola in the Cleveland Philharmonic while at Case, and taught mathematics classes at the college after graduation. He continued on to the California Institute of Technology (Caltech), where he pursued his PhD in physics. His interest in particle physics led him to work with Nobel laureate Carl David Anderson, studying cosmic rays with cloud chambers. He preferred the accessibility of cosmic ray research over that of nuclear physics. While at Caltech he learned to design and build the equipment he needed for his experiments, and this skill would prove to be useful throughout his career. He also attended molecular genetics seminars led by Nobel laureate Max Delbrück; he would return to this field later. Glaser completed his doctoral thesis, The Momentum Distribution of Charged Cosmic Ray Particles Near Sea Level, after starting as an instructor at the University of Michigan in 1949. He received his PhD from Caltech in 1950, and he was promoted to professor at Michigan in 1957 He joined the faculty of UC Berkeley in 1959 as a professor of physics. During this time, his research concerned short-lived elementary particles. The bubble chamber enabled him to observe the paths and lifetimes of the particles. Starting in 1962, Glaser changed his field of research to molecular biology, starting with a project on ultraviolet-induced cancer. In 1964, he was given the additional title of professor of molecular biology. Glaser's position (since 1989) was professor of physics and neurobiology in the graduate school.

Bubble chamber

While teaching at Michigan, Glaser began to work on experiments that led to the creation of the bubble chamber. His experience with cloud chambers at Caltech had shown him that they were inadequate for studying elementary particles. In a cloud chamber, particles pass through gas and collide with metal plates that obscure the scientists' view of the event. The cloud chamber also needs time to reset between recording events and cannot keep up with accelerators' rate of particle production.

He experimented with using superheated liquid in a glass chamber. Charged particles would leave a track of bubbles as they passed through the liquid, and their tracks could be photographed. He created the first bubble chamber with ether. He experimented with hydrogen while visiting the University of Chicago, showing that hydrogen would also work in the chamber.

It has often been claimed that Glaser was inspired to his invention by the bubbles in a glass of beer; however, in a 2006 talk, he refuted this story, saying that although beer was not the inspiration for the bubble chamber, he did experiments using beer to fill early prototypes.

His new invention was ideal for use with high-energy accelerators, so Glaser traveled to Brookhaven National Laboratory with some students to study elementary particles using the accelerator there. The images that he created with his bubble chamber brought recognition of the importance of his device, and he was able to get funding to continue experimenting with larger chambers. Glaser was then recruited by Nobel laureate Luis Alvarez, who was working on a hydrogen bubble chamber at the University of California at Berkeley. Glaser accepted an offer to become a professor of physics there in 1959.

Nobel Prize

Glaser was awarded the 1960 Nobel Prize for Physics for the invention of the bubble chamber. His invention allowed scientists to observe what happens to high-energy beams from an accelerator, thus paving the way for many important discoveries.

#6 Dark Discussions at Cafe Infinity » Colonial Quotes » 2026-01-22 16:22:31

- Jai Ganesh

- Replies: 0

Colonial Quotes

1. Communists have always played an active role in the fight by colonial countries for their freedom, because the short-term objects of Communism would always correspond with the long-term objects of freedom movements. - Nelson Mandela

2. Why are we, as a nation so obsessed with foreign things? Is it a legacy of our colonial years? We want foreign television sets. We want foreign shirts. We want foreign technology. Why this obsession with everything imported? - A. P. J. Abdul Kalam

3. The skills you need to fight the colonial power and the skills you need to gain independence are not necessarily the same you need to run a country. - Kofi Annan

4. Was it not enough punishment and suffering in history that we were uprooted and made helpless slaves not only in new colonial outposts but also domestically. - Robert Mugabe

5. All the sparrows on the rooftops are crying about the fact that the most imperialist nation that is supporting the colonial regime in the colonies is the United States of America. - Nikita Khrushchev

6. Thankfully, Australia has emerged from its inauspicious colonial beginnings to become a proud nation, a nation that overcame those primeval prejudices. - Rupert Murdoch

7. England was the first true colonial power to use its dominion over a large part of Africa, the Middle East, Asia, Australia, North America, and many Caribbean islands, in the first half of the 20th century. - Fidel Castro

8. Famines were frequent in colonial India and some estimates indicate that 30 to 40 million died out of starvation in Tamil Nadu, Bihar and Bengal during the later half of the 19th century. - M. S. Swaminathan.

#7 Re: Jai Ganesh's Puzzles » General Quiz » 2026-01-22 15:53:47

Hi,

#10713. What does the term in Geography Couloir mean?

#10714.. What does the term in Geography Country mean?

#8 Re: Jai Ganesh's Puzzles » English language puzzles » 2026-01-22 15:39:26

Hi,

#5909. What does the noun homestead mean?

#5910. What does the adjective homely mean?

#9 Re: Jai Ganesh's Puzzles » Doc, Doc! » 2026-01-22 15:25:02

Hi,

#2551. What does the medical term Floaters or eye floaters mean?

#10 Jokes » Cherry Jokes - III » 2026-01-22 15:01:47

- Jai Ganesh

- Replies: 0

Q: How do you strike fear into a pie?

A: With a very cherry movie.

* * *

Q: Why were the little cherries upset?

A: Because their parents were in a jam!

* * *

Q: How many grams of protein are in a cherry pi?

A: 3.14159265

* * *

Q: What do you call a fruit that likes to tell jokes?

A: Cherry Seinfeld. Did you hear about the cherry that liked to explode? It was da bomb.

* * *

Q: What do you call a man that can't stop eating cherries whole?

A: A bottomless pit.

* * *

#11 Re: Jai Ganesh's Puzzles » 10 second questions » 2026-01-22 14:49:37

Hi,

#9835.

#12 Re: Jai Ganesh's Puzzles » Oral puzzles » 2026-01-22 14:40:37

Hi,

#6329.

#13 Re: Exercises » Compute the solution: » 2026-01-22 14:29:38

Hi,

2686.

#14 Science HQ » Centre of Gravity (Center of Gravity) » 2026-01-21 22:17:49

- Jai Ganesh

- Replies: 0

Centre of Gravity (Center of Gravity)

Gist

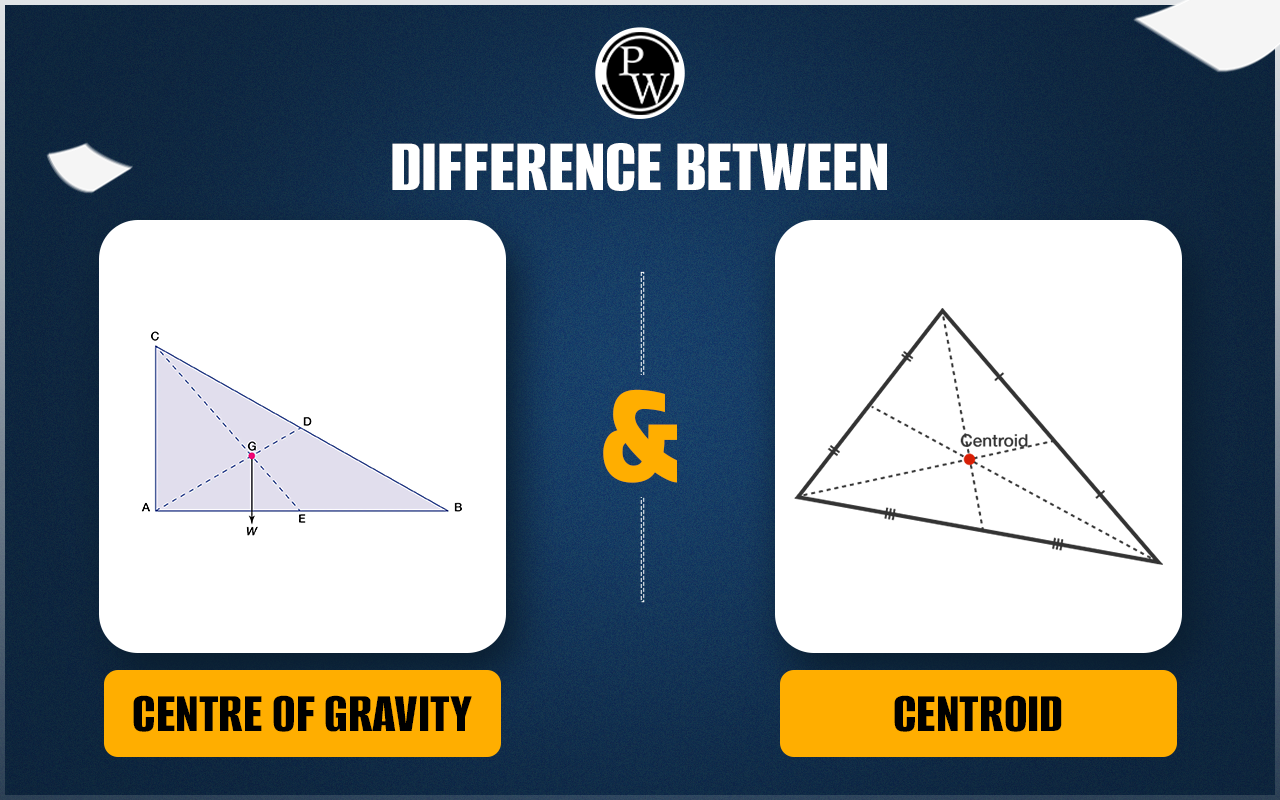

Center of gravity (CG) is the point within an object where its weight is evenly balanced in all directions. Understanding its significance is important because it helps predict how an object will behave when it's moved or supported.

The centre of gravity (CG) of an object is the point at which all of its weight is evenly distributed. It is also known as the centre of mass.

It is important to know the centre of gravity because it predicts the behaviour of a moving body when acted on by gravity. It is also useful in designing static structures such as buildings and bridges. In a uniform gravitational field, the centre of gravity is identical to the centre of mass.

Summary

A body's center of gravity is the point around which the resultant torque due to gravity forces vanishes. Where a gravity field can be considered to be uniform, the center of mass and the center of gravity will be the same. However, for satellites in orbit around a planet, in the absence of other torques being applied to a satellite, the slight variation (gradient) in gravitational field between the parts closer to and further from the planet (stronger and weaker gravity respectively) can lead to a torque that will tend to align the satellite such that its long axis is vertical. In such a case, it is important to make the distinction between the center of gravity and the mass center. Any horizontal offset between the two will result in an applied torque.

The mass center is a fixed property for a given rigid body (e.g., with no slosh or articulation), whereas the center of gravity may, in addition, depend upon its orientation in a non-uniform gravitational field. In the latter case, the center of gravity will always be located somewhat closer to the main attractive body as compared to the mass center, and thus will change its position in the body of interest as its orientation is changed.

In the study of the dynamics of aircraft, vehicles and vessels, forces and moments need to be resolved relative to the mass center. That is true independent of whether gravity itself is a consideration. Referring to the mass center as the center of gravity is something of a colloquialism, but it is in common usage and when gravity gradient effects are negligible, center of gravity and mass center are the same and are used interchangeably.

In physics the benefits of using the center of mass to model a mass distribution can be seen by considering the resultant of the gravity forces on a continuous body.

Details

The centre of gravity, in physics, is an imaginary point in a body of matter where, for convenience in certain calculations, the total weight of the body may be thought to be concentrated. The concept is sometimes useful in designing static structures (e.g., buildings and bridges) or in predicting the behaviour of a moving body when it is acted on by gravity.

In a uniform gravitational field the centre of gravity is identical to the centre of mass, a term preferred by physicists. The two do not always coincide, however. For example, the Moon’s centre of mass is very close to its geometric centre (it is not exact because the Moon is not a perfect uniform sphere), but its centre of gravity is slightly displaced toward Earth because of the stronger gravitational force on the Moon’s near side.

The location of a body’s centre of gravity may coincide with the geometric centre of the body, especially in a symmetrically shaped object composed of homogeneous material. An asymmetrical object composed of a variety of materials with different masses, however, is likely to have a centre of gravity located at some distance from its geometric centre. In some cases, such as hollow bodies or irregularly shaped objects, the centre of gravity (or centre of mass) may occur in space at a point external to the physical material—e.g., in the centre of a tennis ball or between the legs of a chair.

Published tables and handbooks list the centres of gravity for most common geometric shapes. For a triangular metal plate such as that depicted in the figure, the calculation would involve a summation of the moments of the weights of all the particles that make up the metal plate about point A. By equating this sum to the plate’s weight W, multiplied by the unknown distance from the centre of gravity G to AC, the position of G relative to AC can be determined. The summation of the moments can be obtained easily and precisely by means of integral calculus.

The centre of gravity of any body can also be determined by a simple physical procedure. For example, for the plate in the figure, the point G can be located by suspending the plate by a cord attached at point A and then by a cord attached at C. When the plate is suspended from A, the line AD is vertical; when it is suspended from C, the line CE is vertical. The centre of gravity is at the intersection of AD and CE. When an object is suspended from any single point, its centre of gravity lies directly beneath that point.

Additional Information

The center of gravity is a geometric property of any object. The center of gravity is the average location of the weight of an object. We can completely describe the motion of any object through space in terms of the translation of the center of gravity of the object from one place to another, and the rotation of the object about its center of gravity if it is free to rotate. If the object is confined to rotate about some other point, like a hinge, we can still describe its motion. In flight, both airplanes and rockets rotate about their centers of gravity. A kite, on the other hand, rotates about the bridle point. But the trim of a kite still depends on the location of the center of gravity relative to the bridle point, because for every object the weight always acts through the center of gravity.

Determining the center of gravity is very important for any flying object. How do engineers determine the location of the center of gravity for an aircraft which they are designing?

In general, determining the center of gravity (cg) is a complicated procedure because the mass (and weight) may not be uniformly distributed throughout the object. The general case requires the use of calculus which we will discuss at the bottom of this page. If the mass is uniformly distributed, the problem is greatly simplified. If the object has a line (or plane) of symmetry, the cg lies on the line of symmetry. For a solid block of uniform material, the center of gravity is simply at the average location of the physical dimensions.

#15 This is Cool » Itaipu Dam » 2026-01-21 21:46:45

- Jai Ganesh

- Replies: 0

Itaipu Dam

Gist

The world's largest hydroelectric power plant is on the Paraná River between Paraguay and Brazil. The Itaipú Dam is capable of producing 14,000 megawatts of power. The reservoir behind the dam formed in 1982 and covers 1,350 square kilometers. The entire dam is nearly 8 kilometers long.

The Itaipu Hydroelectric Dam is located on the Paraná River on the border between Brazil and Paraguay. The structure which serves to generate power is about 7.9 km long, with a maximum height of 196 m.

Summary

Itaipú Dam is a hollow gravity dam on the Alto (Upper) Paraná River at the Brazil-Paraguay border. It is located north of the town of Ciudad del Este, Paraguay.

In terms of power output, Itaipú Dam is one of the world’s largest hydroelectric projects. Its 20 massive turbine generators, located in the powerhouse at the base of the dam, are capable of generating 14,000 megawatts of electricity. Built as a joint venture by Paraguay and Brazil, the complex of dams and spillways curves across almost 8 km (5 miles) of the Alto Paraná River. The dam itself, built between 1975 and 1982, is 196 metres (643 feet) high and consists of large concrete segments joined to form a hollow chamber. The upstream face is supported by two buttresses, and the downstream face is a simple concrete slab. It is one of the highest and largest hollow gravity dams in the world. Its reservoir stretches northward for about 160 km (100 miles), and it has totally submerged the formerly spectacular Guaíra Falls.

Details

The Itaipu Dam is a hydroelectric dam on the Paraná River located on the border between Brazil and Paraguay. It is the third-largest hydroelectric dam in the world in terms of produced energy.

The name "Itaipu" was taken from an island that existed near the construction site. In the Guarani language, Itaipu means "the sounding stone." As of 2020, the Itaipu Dam's hydroelectric power plant produced the second-largest amount of electricity of any hydroelectric power plant in the world, with its electricity production being only surpassed by the Three Gorges Dam plant in China. Additionally, Itaipu also holds the 45th largest reservoir in the world.

With its construction completed in 1984, it is a binational undertaking run by Brazil and Paraguay at the border between the two countries, 15 km (9.3 mi) north of the Friendship Bridge. The project ranges from Foz do Iguaçu, in Brazil, and Ciudad del Este in Paraguay, in the south to Guaíra and Salto del Guairá in the north. The installed generation capacity of the plant is 14 GW, with 20 generating units providing 700 MW each with a hydraulic design head of 118 metres (387 ft). In 2016, the plant employed 3038 workers.

Of the twenty generator units currently installed, ten generate at 50 Hz for Paraguay and ten generate at 60 Hz for Brazil. Since the output capacity of the Paraguayan generators far exceeds the load in Paraguay, most of their production is exported directly to the Brazilian side, from where two 600 kV HVDC lines, each approximately 800 kilometres (500 mi) long, carry the majority of the energy to the São Paulo/Rio de Janeiro region where the terminal equipment converts the power to 60 Hz.

Additional Information

The Itaipu Dam is a hydroelectric (making electricity by the movement of water) dam on the Paraná River, on the border between Brazil and Paraguay.

It is listed as one of the Seven Wonders of the Modern World. It is the world's second largest dam behind the Three Gorges Dam and is 7919 metres long and 196 metres high. It is the second-largest power plant in the world by nameplate capacity and the largest by power production in 2015-2016.

The Itaipu Dam is owned by the Brazilian Government.

#16 Re: Dark Discussions at Cafe Infinity » crème de la crème » 2026-01-21 17:11:56

2416) Georg von Békésy

Gist:

Work

Our hearing works because sound waves from the surrounding world are converted in the ear into vibrations in membranes and bones. These are further converted into electrical impulses that are passed on to the brain, resulting in auditory impressions. In a series of studies from 1940 to the 1960s, Georg von Békésy clarified how processes in the cochlea in the inner ear proceed, in part by studying vibrations in membranes with the help of a microscope and sequences of photographs as well as by measuring variations in electrical charges in the receptors.

Summary

Georg von Békésy (born June 3, 1899, Budapest, Hungary—died June 13, 1972, Honolulu, Hawaii, U.S.) was an American physicist and physiologist who received the 1961 Nobel Prize for Physiology or Medicine for his discovery of the physical means by which sound is analyzed and communicated in the cochlea, a portion of the inner ear.

As director of the Hungarian Telephone System Research Laboratory (1923–46), Békésy worked on problems of long-distance communication and became interested in the mechanics of human hearing. At the telephone laboratory, the University of Budapest (1939–46), the Karolinska Institute, Stockholm (1946–47), and Harvard University (1947–66) he conducted intensive research that led to the construction of two cochlea models and highly sensitive instruments that made it possible to understand the hearing process, differentiate between certain forms of deafness, and select proper treatment more accurately.

Since the mid-19th century, it had been known that the vibratory tissue most important for hearing is the basilar membrane, stretching the length of the snail-shaped cochlea and dividing it into two interior canals. Békésy found that sound travels along the basilar membrane in a series of waves, and he demonstrated that these waves peak at different places on the membrane: low frequencies toward the end of the cochlea and high frequencies near its entrance, or base. He discovered that the location of the nerve receptors and the number of receptors involved are the most important factors in determining pitch and loudness.

Békésy became professor of sensory sciences at the University of Hawaii in 1966. His books include Experiments in Hearing (1960) and Sensory Inhibition (1967).

Details

Georg von Békésy (3 June 1899 – 13 June 1972) was a Hungarian-American biophysicist.

By using strobe photography and silver flakes as a marker, he was able to observe that the basilar membrane moves like a surface wave when stimulated by sound. Because of the structure of the cochlea and the basilar membrane, different frequencies of sound cause the maximum amplitudes of the waves to occur at different places on the basilar membrane along the coil of the cochlea. High frequencies cause more vibration at the base of the cochlea while low frequencies create more vibration at the apex.

He concluded that his observations showed how different sound wave frequencies are locally dispersed before exciting different nerve fibers that lead from the cochlea to the brain.

In 1961, he was awarded the Nobel Prize in Physiology or Medicine for his research on the function of the cochlea in the mammalian hearing organ.

Biography

Békésy was born on 3 June 1899 in Budapest, Hungary, as the first of three children (György 1899, Lola 1901 and Miklós 1903) to Sándor Békésy (1860–1923), an economic diplomat, and to his mother Paula Mazaly.

The Békésy family was originally Reformed but converted to Catholicism. His mother, Paula Mazaly (1877–1974) was born in Szagolyca (now Čađavica, Croatia). His maternal grandfather was from Pécs. His father was born in Kolozsvár (now Cluj-Napoca, Romania).

Békésy went to school in Budapest, Munich, and Zürich. He studied chemistry in Bern and received his PhD in physics on the subject: "Fast way of determining molecular weight" from the University of Budapest in 1926.

He then spent one year working in an engineering firm. He published his first paper on the pattern of vibrations of the inner ear in 1928. He was offered a position at Uppsala University by Róbert Bárány, which he declined because of the hard Swedish winters.

Before and during World War II, Békésy worked for the Hungarian Post Office (1923 to 1946), where he did research on telecommunications signal quality. This research led him to become interested in the workings of the ear. In 1946, he left Hungary to follow this line of research at the Karolinska Institute in Sweden.

In 1947, he moved to the United States, working at Harvard University until 1966. In 1962 he was elected a Member of the German Academy of Sciences Leopoldina. After his lab was destroyed by fire in 1965, he was invited to lead a research laboratory of sense organs in Honolulu, Hawaii. He became a professor at the University of Hawaiʻi in 1966 and died in Honolulu.

He became a well-known expert in Asian art. He had a large collection which he donated to the Nobel Foundation in Sweden. His brother, Dr. Miklós Békésy (1903-1980), stayed in Hungary and became a famous agrobiologist who was awarded the Kossuth Prize.

Research

Békésy contributed most notably to our understanding of the mechanism by which sound frequencies are registered in the inner ear. He developed a method for dissecting the inner ear of human cadavers while leaving the cochlea partly intact. By using strobe photography and silver flakes as a marker, he was able to observe that the basilar membrane moves like a surface wave when stimulated by sound. Because of the structure of the cochlea and the basilar membrane, different frequencies of sound cause the maximum amplitudes of the waves to occur at different places on the basilar membrane along the coil of the cochlea. High frequencies cause more vibration at the base of the cochlea while low frequencies create more vibration at the apex.

Békésy concluded from these observations that by exciting different locations on the basilar membrane different sound wave frequencies excite different nerve fibers that lead from the cochlea to the brain. He theorized that, due to its placement along the cochlea, each sensory cell (hair cell) responds maximally to a specific frequency of sound (the so-called tonotopy). Békésy later developed a mechanical model of the cochlea, which confirmed the concept of frequency dispersion by the basilar membrane in the mammalian cochlea.

In an article published posthumously in 1974, Békésy reviewed progress in the field, remarking "In time, I came to the conclusion that the dehydrated cats and the application of Fourier analysis to hearing problems became more and more a handicap for research in hearing," referring to the difficulties in getting animal preparations to behave as when alive, and the misleading common interpretations of Fourier analysis in hearing research.

#17 Re: This is Cool » Miscellany » 2026-01-21 16:44:30

2476) The Alps

The Alps

Gist

The Alps are Europe's highest and most extensive mountain range, forming a crescent across eight countries (France, Switzerland, Italy, Austria, Germany, Slovenia, Liechtenstein, Monaco), famous for Mont Blanc, Matterhorn, stunning scenery, skiing, biodiversity, and unique climate zones, originating from tectonic plate collision and providing vital water sources for Europe.

Which countries are in the Alps?

They stretch across eight countries: France, Switzerland, Italy, Monaco, Liechtenstein, Austria, Germany and Slovenia. The mountains were formed millions of years ago as two giant tectonic plates collided, creating some of the highest mountains in Europe, like the Matterhorn, Mont Blanc, and the Eiger.

Summary

The Alps are some of the highest and most extensive mountain ranges in Europe, stretching approximately 1,200 km (750 mi) across eight Alpine countries (from west to east): Monaco, France, Switzerland, Italy, Liechtenstein, Germany, Austria, Slovenia, and Hungary.

The Alpine arch extends from Nice on the western Mediterranean to Trieste on the Adriatic and Vienna at the beginning of the Pannonian Basin. The mountains were formed over tens of millions of years as the African and Eurasian tectonic plates collided. Extreme shortening caused by the event resulted in marine sedimentary rocks rising by thrusting and folding into high mountain peaks such as Mont Blanc and the Matterhorn.

Mont Blanc spans the French–Italian border, and at 4,809 m (15,778 ft) is the highest mountain in the Alps. The Alpine region area contains 82 peaks higher than 4,000 m (13,000 ft).

The altitude and size of the range affect the climate in Europe; in the mountains, precipitation levels vary greatly and climatic conditions consist of distinct zones. Wildlife such as ibex live in the higher peaks to elevations of 3,400 m (11,155 ft), and plants such as edelweiss grow in rocky areas in lower elevations as well as in higher elevations.

Evidence of human habitation in the Alps goes back to the Palaeolithic era. A mummified man ("Ötzi"), determined to be 5,000 years old, was discovered on a glacier at the Austrian–Italian border in 1991.

By the 6th century BC, the Celtic La Tène culture was well established. Hannibal notably crossed the Alps with a herd of elephants, and the Romans had settlements in the region. In 1800, Napoleon crossed one of the mountain passes with an army of 40,000. The 18th and 19th centuries saw an influx of naturalists, writers, and artists, in particular, the Romanticists, followed by the Golden Age of Alpinism as mountaineers began to ascend the peaks of the Alps.

The Alpine region has a strong cultural identity. Traditional practices such as farming, cheese making, and woodworking still thrive in Alpine villages. However, the tourist industry began to grow early in the 20th century and expanded significantly after World War II, eventually becoming the dominant industry by the end of the century.

The Winter Olympic Games have been hosted in the Swiss, French, Italian, Austrian and German Alps. As of 2010, the region is home to 14 million people and has 120 million annual visitors.

Details

Alps, a small segment of a discontinuous mountain chain that stretches from the Atlas Mountains of North Africa across southern Europe and Asia to beyond the Himalayas. The Alps extend north from the subtropical Mediterranean coast near Nice, France, to Lake Geneva before trending east-northeast to Vienna (at the Vienna Woods). There they touch the Danube River and meld with the adjacent plain. The Alps form part of France, Italy, Switzerland, Germany, Austria, Slovenia, Croatia, Bosnia and Herzegovina, Montenegro, Serbia, and Albania. Only Switzerland and Austria can be considered true Alpine countries, however. Some 750 miles (1,200 kilometres) long and more than 125 miles wide at their broadest point between Garmisch-Partenkirchen, Germany, and Verona, Italy, the Alps cover more than 80,000 square miles (207,000 square kilometres). They are the most prominent of western Europe’s physiographic regions.

Though they are not as high and extensive as other mountain systems uplifted during the Paleogene and Neogene periods (i.e., about 65 million to 2.6 million years ago)—such as the Himalayas and the Andes and Rocky mountains—they are responsible for major geographic phenomena. The Alpine crests isolate one European region from another and are the source of many of Europe’s major rivers, such as the Rhône, Rhine, Po, and numerous tributaries of the Danube. Thus, waters from the Alps ultimately reach the North, Mediterranean, Adriatic, and Black seas. Because of their arclike shape, the Alps separate the marine west-coast climates of Europe from the Mediterranean areas of France, Italy, and the Balkan region. Moreover, they create their own unique climate based on both the local differences in elevation and relief and the location of the mountains in relation to the frontal systems that cross Europe from west to east. Apart from tropical conditions, most of the other climates found on the Earth may be identified somewhere in the Alps, and contrasts are sharp.

A distinctive Alpine pastoral economy that evolved through the centuries has been modified since the 19th century by industry based on indigenous raw materials, such as the industries in the Mur and Mürz valleys of southern Austria that used iron ore from deposits near Eisenerz. Hydroelectric power development at the end of the 19th and beginning of the 20th centuries, often involving many different watersheds, led to the establishment in the lower valleys of electricity-dependent industries, manufacturing such products as aluminum, chemicals, and specialty steels. Tourism, which began in the 19th century in a modest way, became, after World War II, a mass phenomenon. Thus, the Alps are a summer and winter playground for millions of European urban dwellers and annually attract tourists from around the world. Because of this enormous human impact on a fragile physical and ecological environment, the Alps are likely the most threatened mountain system in the world.

Physical features:

Geology