Math Is Fun Forum

You are not logged in.

- Topics: Active | Unanswered

#1 Re: This is Cool » Miscellany » Today 00:04:26

2521) Odometer

Gist

An odometer is an instrument on a vehicle's dashboard that measures and displays the total distance traveled, typically in miles or kilometers. It works via mechanical gears or electronic sensors (on modern cars) tracking wheel rotations to determine distance, crucial for maintenance tracking and resale value.

Odometer includes the root from the Greek word hodos, meaning "road" or "trip". An odometer shares space on your dashboard with a speedometer, a tachometer, and maybe a "tripmeter". The odometer is what crooked car salesmen tamper with when they want to reduce the mileage a car registers as having traveled.

Summary

An odometer is a device that registers the distance traveled by a vehicle. Modern digital odometers use a computer chip to track mileage. They make use of a magnetic or optical sensor that tracks pulses of a wheel that connects to a vehicle’s tires. This data is stored in the engine control module (ECM). Odometers use these stored values to determine the total distance traveled by a vehicle.

Analog or mechanical odometers consist of a train of gears (with a gear ratio of 1,000:1) that causes a drum, classified in tenths of a mile or kilometre, to make one turn per mile or kilometre. A series of usually six such drums is arranged in such a way that one of the numerals on each drum is visible in a rectangular window. The drums are coupled so that 10 revolutions of the first cause one revolution of the second, and so forth, with the numbers appearing in the window representing the vehicle’s accumulated mileage.

The Roman architect and engineer Vitruvius is credited with inventing the initial version of an odometer in 15 bce. The concept consisted of a chariot wheel that turned 400 times to show one Roman mile. This wheel was mounted in a frame with a 400-tooth cogwheel. For every 400 rotations of the chariot wheel, the cogwheel would drop one pebble. In 1642 the French mathematician Blaise Pascal used the same principle to create an apparatus that used gears and wheels. For every 10 rotations of a gear, a second gear advanced one place. The modern odometer was invented about 1847 by pioneers William Clayton and Orson Pratt, members of the Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints. They attached their apparatus to a wagon wheel while they traversed the plains from Nebraska to the Great Salt Lake valley.

Details

An automobile’s most prominent yet unexplored part is the odometer. It is placed behind the steering wheel on the dashboard. It displays the distance the car has run. Odometer readings are beneficial to car owners when selling the vehicle. It helps evaluate the mileage or plans for car service.

Odometers can be mechanical, electrical, or a combination of the two. They are also known as mileometer or milometers in countries with imperial units or US customary units. Odometer is the most widely used name, especially in the UK and the Commonwealth countries.

Meaning

An odometer is a device used to measure the displacement of an object. It measures the distance travelled between the start point and the endpoint. Odometer is derived from two Greek words that mean path and measure.

Who invented the odometer?

Vitruvius, a Roman architect and engineer, is credited for the invention of the odometer in the 15th century. He used a standard chariot wheel, mounted on a frame with a 400-teeth cogwheel, and turned it 400 times in a Roman mile. The cogwheel employed a gear that slipped a stone into the box for every mile. Thus, it helped learn the miles covered by counting the pebbles.

In the 16th century, Blaise Pascal invented a calculating machine called Pascaline. It was a prototype of an odometer—the Pascaline comprised gears and wheels, where each gear had ten teeth. Every time a tooth completed a revolution, the second gear was engaged. This principle is used in the mechanical odometer.

English military engineer Thomas Savery invented an odometer for ships. In 1775, Ben Franklin, a statesman and a writer, created a simple odometer that measured the mileage of the routes. He attached it to his carriage.

In 1847, the Mormon Pioneers invented an odometer while crossing the plains from Missouri to Utah. Also known as a roadometer, they attached it to the wagon’s wheel, and when the wagon started the journey, it counted the wheel revolutions. Orson Pratt and William Clayton designed the odometer, and Appleton Milo Harmon, the carpenter, built it.

In 1854, Nova Scotia’s Samuel McKeen designed another early version of the odometer. The device measured driven mileage. He attached the device to the carriage side and measured the miles with wheels turning.

Types of odometer:

There are two types of odometers.

1) Mechanical odometers

2) Electronic odometers

Mechanical odometers

Mechanical odometers start with the transmission. The transmission system contains a small gear that measures the odometer advancing. This small gear is connected to the speedometer drive cable. The other end of this cable is connected to the instrument cluster.

The internal transmission gear turns when the engine is turned on, and the car starts moving. This internal transmission gear motion is conveyed to another set of gears linked to changeable digits by the connected drive cable. Thus, the counting begins from the right side of the group of numbers.

The process continues till the distance travelled by automobile compels the left side digits to roll over. This counting process repeats until all the adjacent numbers touch their apex values. Then, all the digits are set back to zero, and it starts again.

Mechanical odometers are not always precise and a hundred per cent accurate.

Electronic odometers

After the mechanical odometers came the electronic ones. They are also known as digital odometers. They depend on the automobile’s electronics for establishing accurate mileage.

Electronic odometers, like mechanical ones, employ a special gear for changing the count seen on the dashboard. In addition, a magnetic sensor replaces the drive cable to track the gear turns in the transmission. The wires conduct the obtained signal to the car’s onboard computer that interprets and converts the data into mileage count.

The advantage of electronic odometers over mechanical ones is that they provide better accuracy. In addition, no one can manipulate electronic odometers easily, hence giving an accurate count of the vehicle’s mileage.

Odometers come with an additional trip meter called a trip odometer. It helps the car owners determine the mileage for any particular distance without interfering with the primary odometer reading.

Conclusion

The primary purpose of an odometer is to measure the distance travelled by the vehicle. In addition, odometer readings help determine various maintenance milestones such as tyre rotations, oil changes etc. Dealers use odometer readings to estimate the vehicle’s valuation in the used car market. Resetting odometer values require changing the entire transmission system of a car. Hence, odometer readings are very difficult to reset. Also, tampering with the reading is considered a fraud and punishable by law.

Additional Information

Mechanical odometers have been counting the miles for centuries. Although they are a dying breed, they are incredibly cool because they are so simple! A mechanical odometer is nothing more than a gear train with an incredible gear ratio.

The odometer we took apart for this article has a 1690:1 gear reduction! That means the input shaft of this odometer has to spin 1,690 times before the odometer will register 1 mile.

Odometers like this are being replaced by digital odometers that provide more features and cost less, but they aren't nearly as cool. In this article, we'll take a look inside a mechanical odometer, and then we'll talk about how digital odometers work.

Mechanical Odometers

Mechanical odometers are turned by a flexible cable made from a tightly wound spring. The cable usually spins inside a protective metal tube with a rubber housing. On a bicycle, a little wheel rolling against the bike wheel turns the cable, and the gear ratio on the odometer has to be calibrated to the size of this small wheel. On a car, a gear engages the output shaft of the transmission, turning the cable.

The cable snakes its way up to the instrument panel, where it is connected to the input shaft of the odometer.

The Gearing

This odometer uses a series of three worm gears to achieve its 1690:1 gear reduction. The input shaft drives the first worm, which drives a gear. Each full revolution of the worm only turns the gear one tooth. That gear turns another worm, which turns another gear, which turns the last worm and finally the last gear, which is hooked up to the tenth-of-a-mile indicator.

Each indicator has a row of pegs sticking out of one side, and a single set of two pegs on the other side. When the set of two pegs comes around to the white plastic gears, one of the teeth falls in between the pegs and turns with the indicator until the pegs pass. This gear also engages one of the pegs on the next bigger indicator, turning it a tenth of a revolution.

On the white wheel between the "3" and the "4," there are two pegs. One time per revolution, one of the gear teeth on the white gear falls in between these two pegs, causing the black gear next to it to move one-tenth of a revolution.

You can now see why, when your odometer "rolls over" a large number of digits (say from 19,999 to 20,000 miles), the "2" at the far left side of the display may not line up perfectly with the rest of the digits. A tiny amount of gear lash in the white helper gears prevents perfect alignment of all the digits. Usually, the display will have to get to 21,000 miles before the digits line up well again.

You can also see that mechanical odometers like this one are rewindable. In many older vehicles, driving in reverse could cause the mechanical odometer to run backward due to the straightforward gear mechanism. However, some mechanical odometers were equipped with mechanisms to prevent reverse counting, ensuring the mileage only increased regardless of the driving direction.

In the movie "Ferris Bueller's Day Off," in the scene where they have the car up on blocks with the wheels spinning in reverse -- that should've worked! In real life, the odometer would've turned back. Another trick is to hook the odometer's cable up to a drill and run it backwards to rewind the miles.

Computerized Odometers

If you make a trip to the bike shop, you most likely won't find any cable-driven odometers or speedometers. Instead, you will find bicycle computers. Bicycles with computers like these have a magnet attached to one of the wheels and a pickup attached to the frame. Once per revolution of the wheel, the magnet passes by the pickup, generating a voltage in the pickup. The computer counts these voltage spikes, or pulses, and uses them to calculate the distance traveled.

If you have ever installed one of these bike computers, you know that you have to program them with the circumference of the wheel. The circumference is the distance traveled when the wheel makes one full revolution. Each time the computer senses a pulse, it adds another wheel circumference to the total distance and updates the digital display.

Many modern cars use a system like this, too. Instead of a magnetic pickup on a wheel, they use a toothed wheel mounted to the output of the transmission and a magnetic sensor that counts the pulses as each tooth of the wheel goes by. Some cars use a slotted wheel and an optical pickup, like a computer mouse does. Just like on the bicycle, the computer in the car knows how much distance the car travels with each pulse, and uses this to update the odometer reading.

One of the most interesting things about car odometers is how the information is transmitted to the dashboard. Instead of a spinning cable transmitting the distance signal, the distance (along with a lot of other data) is transmitted over a single wire communications bus from the engine control unit (ECU) to the dashboard. The car is like a local area network with many different devices connected to it. Here are some of the devices that may be connected to the computer network in a car:

* Engine control unit (ECU)

* Climate control system

* Dashboard

* Power window controls

* Radio

* Anti-lock braking system

* Air bag control module

* Body control module (operates the interior lights, etc.)

* Transmission control module

Many vehicles use a standardized communication protocol, called SAE J1850, to enable all of the different electronics modules to communicate with each other.

The engine control unit counts all of the pulses and keeps track of the overall distance traveled by the car. This means that if someone tries to "roll back" the odometer, the value stored in the ECU will disagree. This value can be read using a diagnostic computer, which all car-dealership service departments have.

Several times per second, the ECU sends out a packet of information consisting of a header and the data. The header is just a number that identifies the packet as a distance reading, and the data is a number corresponding to the distance traveled. The instrument panel contains another computer that knows to look for this particular packet, and whenever it sees one it updates the odometer with the new value. In cars with digital odometers, the dashboard simply displays the new value. Cars with analog odometers have a small stepper motor that turns the dials on the odometer.

#2 Re: Dark Discussions at Cafe Infinity » crème de la crème » Today 00:04:00

2458) Felix Bloch

Gist:

Life

Felix Bloch was born in Zurich, Switzerland, the son of a merchant, and studied at ETH and elsewhere. When the Nazis took power in 1933, he left Europe to work at Stanford University. After becoming an American citizen, he worked on atomic energy in Los Alamos during World War II and later on radar at Harvard University. Immediately after the war, he did his Nobel Prize-awarded work at Stanford. He became the first head of CERN outside Geneva in 1954-1955. Bloch was married and had four children.

Work

Protons and neutrons in nuclei act like small, rotating magnets. Atoms and molecules therefore align in a magnetic field. Radio waves can disturb their direction of rotation, but only in certain stages, in accordance with quantum mechanics. When the atoms return to their original positions, they emit electromagnetic radio waves with frequencies characteristic of different elements and isotopes. In 1946, Felix Bloch and Edward Purcell developed methods for precise measurement, making it possible to study different materials’ compositions.

Summary

Felix Bloch (born Oct. 23, 1905, Zürich, Switz.—died Sept. 10, 1983, Zürich) was a Swiss-born American physicist who shared (with E.M. Purcell) the Nobel Prize for Physics in 1952 for developing the nuclear magnetic resonance method of measuring the magnetic field of atomic nuclei.

Bloch’s doctoral dissertation (University of Leipzig, 1928) promulgated a quantum theory of solids that provided the basis for understanding electrical conduction. Bloch taught at the University of Leipzig until 1933; when Adolf Hitler came to power he emigrated to the United States and was naturalized in 1939. After joining the faculty of Stanford University, Palo Alto, Calif., in 1934, he proposed a method for splitting a beam of neutrons into two components that corresponded to the two possible orientations of a neutron in a magnetic field. In 1939, using this method, he and Luis Alvarez (winner of the Nobel Prize for Physics in 1968) measured the magnetic moment of the neutron (a property of its magnetic field). Bloch worked on atomic energy at Los Alamos, N.M., and radar countermeasures at Harvard University during World War II.

Bloch returned to Stanford in 1945 to develop, with physicists W.W. Hansen and M.E. Packard, the principle of nuclear magnetic resonance, which helped establish the relationship between nuclear magnetic fields and the crystalline and magnetic properties of various materials. It later became useful in determining the composition and structure of molecules. Nuclear magnetic resonance techniques have become increasingly important in diagnostic medicine.

Bloch was the first director general of the European Organization for Nuclear Research (1954–55; CERN).

Details

Felix Bloch (23 October 1905 – 10 September 1983) was a Swiss-American theoretical physicist who shared the 1952 Nobel Prize in Physics with Edward Mills Purcell "for their development of new methods for nuclear magnetic precision measurements and discoveries in connection therewith".

He was the first Stanford University Nobel laureate.

Bloch made fundamental theoretical contributions to the understanding of ferromagnetism and electron behavior in crystal lattices. He is also considered one of the developers of nuclear magnetic resonance.

Education

Bloch was born on 23 October 1905 in Zurich, Switzerland, to Jewish parents, Gustav Bloch and Agnes Mayer. Gustav was financially unable to attend university and worked as a wholesale grain dealer in Zurich. Gustav moved to Zurich from Moravia in 1890 to become a Swiss citizen. Their first child was a girl born in 1902, while Felix was born three years later.

Bloch entered public elementary school at the age of six and is said to have been teased, in part because he "spoke Swiss German with a somewhat different accent than most members of the class". He received support from his older sister during much of this time, but she died at the age of 12, devastating Felix, who is said to have lived a "depressed and isolated life" in the following years. Bloch learned to play the piano by the age of 8 and was drawn to arithmetic for its "clarity and beauty". Bloch graduated from elementary school at twelve and enrolled in the Cantonal Gymnasium in Zurich for secondary school in 1918. He was placed on a six-year curriculum here to prepare him for university. He continued his curriculum through 1924, even through his study of engineering and physics in other schools, though it was limited to mathematics and languages after the first three years.

After these first three years at the Gymnasium, at the age of 15, Bloch began to study at the ETH Zurich. Although he initially studied engineering, he soon changed to physics. During this time, he attended lectures and seminars given by Peter Debye and Hermann Weyl at the ETH Zurich and Erwin Schrödinger at the neighboring University of Zurich. A fellow student in these seminars was John von Neumann.

Bloch graduated in 1927, and was encouraged by Debye to go to the University of Leipzig to study under Werner Heisenberg. Bloch became Heisenberg's first graduate student, and gained his doctorate in 1928. His doctoral thesis established the quantum theory of solids, using waves to describe electrons in periodic lattices.

Career and research

Bloch remained in European academia, working on superconductivity with Wolfgang Pauli in Zurich; with Hans Kramers and Adriaan Fokker in the Netherlands; with Heisenberg on ferromagnetism, where he developed a description of boundaries between magnetic domains, now known as Bloch walls, and theoretically proposed a concept of spin waves, excitations of magnetic structure; with Niels Bohr in Copenhagen, where he worked on a theoretical description of the stopping of charged particles traveling through matter; and with Enrico Fermi in Rome.

In 1932, Bloch returned to Leipzig to assume a position as Privatdozent (lecturer). In 1933, immediately after Adolf Hitler came to power, Bloch left Germany out of fear of anti-Jewish persecution, returning to Zurich before traveling to Paris to lecture at the Institut Henri Poincaré.

In 1934, the chairman of Stanford Physics invited Bloch to join the faculty. Bloch accepted the offer and emigrated to the United States. In the fall of 1938, Bloch began working with the 37 inch cyclotron at the University of California, Berkeley, to determine the magnetic moment of the neutron. Bloch went on to become the first professor of theoretical physics at Stanford. In 1939, he became a naturalized citizen of the United States.

During World War II, Bloch briefly worked on the atomic bomb project at Los Alamos. Disliking the military atmosphere of the laboratory and uninterested in the theoretical work there, Bloch left to join the radar project at Harvard University.

After the war, he concentrated on investigations into nuclear induction and nuclear magnetic resonance, which are the underlying principles of MRI. In 1946, he proposed the Bloch equations, which determine the time evolution of nuclear magnetization. He was elected to the National Academy of Sciences in 1948. Along with Edward Purcell, Bloch was awarded the Nobel Prize in Physics in 1952 for his work on nuclear magnetic induction.

When CERN was being set up in the early 1950s, its founders were searching for someone of stature and international prestige to head the fledgling international laboratory, and in 1954 Professor Bloch became CERN's first director-general, at the time when construction was getting under way on the present Meyrin site and plans for the first machines were being drawn up. After leaving CERN, he returned to Stanford University, where he in 1961 was made Max Stein Professor of Physics.

In 1964, he was elected a foreign member of the Royal Netherlands Academy of Arts and Sciences. He was also a member of the American Academy of Arts and Sciences and the American Philosophical Society.

Family

On 14 March 1940, Bloch married Lore Clara Misch (1911–1996), a fellow physicist working on X-ray crystallography, whom he had met at an American Physical Society meeting. They had four children, twins George Jacob Bloch and Daniel Arthur Bloch (born 15 January 1941), son Frank Samuel Bloch (born 16 January 1945), and daughter Ruth Hedy Bloch (born 15 September 1949).

Bloch died on 10 September 1983 in Zurich at the age of 77. In 2025 Bloch's family donated his Nobel Prize medal to CERN.

#3 Jokes » Nut Jokes - III » Today 00:03:35

- Jai Ganesh

- Replies: 0

Q: What did the bird say to the racing squirrel?

A: You walnut beat that!

* * *

Q: How many squirrels does it take to change a light bulb?

A: Actually, none because squirrels only change bulbs that are NUT broken.

* * *

Q: Why does it take more than one squirrel to screw in a lightbulb?

A: Because they're so darn stupid!

* * *

Q: Why was the squirrel late for work?

A: Traffic was NUTS.

* * *

Q: How do you catch a carpenter squirrel (definition: a squirrel that likes power tools)?

A: Go to Home Depot and pretend to be nut-wood.

* * *

#4 Dark Discussions at Cafe Infinity » Comedy Quotes - II » Today 00:02:56

- Jai Ganesh

- Replies: 0

Comedy Quotes - II

1. We participate in a tragedy; at a comedy we only look. - Aldous Huxley

2. Friends applaud, the comedy is over. - Ludwig van Beethoven

3. I am completely open to doing a romantic comedy, but I will never do something just for the sake of doing a specific genre or because it's the time or place to do a different type of movie. I think that would be a huge mistake. - Leonardo DiCaprio

4. I will do comedy until the day I die: inappropriate comedy, funny comedy, gender-bending, twisting comedy, whatever comedy is out there. - Sandra Bullock

5. Even actresses that you really admire, like Reese Witherspoon, you think, 'Another romantic comedy?' You see her in something like 'Walk the Line' and think, 'God, you're so great!' And then you think, 'Why is she doing these stupid romantic comedies?' But of course, it's for money and status. - Gwyneth Paltrow

6. When I tried to branch out into comedy, I didn't do very well at it, so I went back to doing what I do naturally well, or what the audience expects from me - action pictures. - Sylvester Stallone

7. As for doing more dramatic work over comedy, I do whatever turns me on at the moment. - Sandra Bullock

8. I think that you can fall into bad habits with comedy... It's a tightrope to stay true to the character, true to the irony, and allow the irony to happen. - Ben Kingsley

#5 This is Cool » Field Vision Test » Yesterday 18:17:05

- Jai Ganesh

- Replies: 0

Field Vision Test

Gist

A visual field test (perimetry) maps your peripheral and central vision to detect blind spots (scotomas). It is essential for diagnosing and managing glaucoma, neurological conditions (e.g., MS, tumors, strokes), and monitoring medication side effects. Typically lasting 5–10 minutes per eye, patients click a button when they see light flashes while staring at a central point.

A visual field test can determine if you have blind spots, known as scotomas, in your vision and where they are. A blind spot's size and shape can show how eye disease or a brain disorder is affecting your vision.

Summary

A visual field test is an eye examination that can detect dysfunction in central and peripheral vision which may be caused by various medical conditions such as glaucoma, stroke, pituitary disease, brain tumours or other neurological deficits. Visual field testing can be performed clinically by keeping the subject's gaze fixed while presenting objects at various places within their visual field. Simple manual equipment can be used such as in the tangent screen test or the Amsler grid. When dedicated machinery is used it is called a perimeter.

The exam may be performed by a technician in one of several ways. The test may be performed by a technician directly, with the assistance of a machine, or completely by an automated machine. Machine-based tests aid diagnostics by allowing a detailed printout of the patient's visual field.

Details

A visual field test measures your peripheral vision, or how well you can see above, below and to the sides of something you’re looking at. It’s also called a perimetry test. Visual field testing is important for many conditions, including glaucoma.

Overview:

What is a visual field test?

A visual field test is a simple and painless test an eye care provider gives you to diagnose or monitor various eye conditions.

A visual field test measures two things:

* How far up, down, left and right your eye sees without moving (when you’re looking straight ahead).

* How sensitive your vision is in different parts of the visual field, which is the name for the entire area that you can see.

Your eyes normally see a wide area of the space in front of you. Without moving your eyes, you can see not only what’s straight ahead, but also some of what’s above, below and off to either side. Providers call all of the area you can see that isn’t right in front of you “peripheral vision.” This surrounds the area that’s right in front of you that you can see (central vision).

Vision is usually best right in the middle of the visual field, so you probably turn your eyes toward the things you want to see more clearly. The farther away from the center of your vision an object is, the less clearly you can see it. When an object moves far enough to the side, it disappears from your vision completely.

When is a visual field test performed?

When you visit an optometrist or ophthalmologist, a visual field test is part of a routine eye exam. Visual field testing can help your eye care provider find early signs of diseases like glaucoma that gradually damage vision. Some people with glaucoma don’t notice any problems with their vision, but the visual field test shows a loss of peripheral vision.

A visual field test can also help your provider find out more about the part of your nervous system that allows you to see. The visual part of your nervous system includes:

* Your retina, the part of your eye that’s like a translator that changes light energy into an electrical signal.

* Your optic nerve, the nerve that carries the signals to your brain so they can become images.

* Your brain, the place where the signals become the images you see.

Issues with any part of this system can change your visual field. There are well-known patterns in the test results that help providers recognize certain types of injury or disease.

By repeating visual field tests at regular intervals, providers also can tell whether your condition is getting better or worse.

Medical conditions that might cause a provider to order a visual field test

Your healthcare provider may want you to have a visual field test if you have (or they think you may have) certain conditions. Providers use the results to both diagnose and monitor conditions such as:

* Glaucoma.

* Stroke.

* Macular degeneration.

* Multiple sclerosis (MS).

* Graves’ disease.

* Pituitary gland disease.

* Blind spot (scotoma).

Why do some people need to have visual field tests many times?

Sometimes your eye care provider will want to repeat the visual field test right away to make sure the results are accurate. If you’re tired, for example, the test results can be unreliable.

Your provider might also recommend that you take a visual field test again in a few weeks, a few months or a year. This might be necessary to make sure that they find any new problems early. When you have certain eye conditions, your provider will do visual field tests regularly to find out how well the treatment is working.

Visual field tests are especially important in the treatment of glaucoma. These tests will tell the provider if you’re losing vision even before you notice. That’s just one of the reasons why people who have glaucoma should keep all of their appointments with their provider.

Test Details:

What happens during a visual field test?

You don’t have to prepare for a visual field test. It’s not invasive, so you aren’t likely to have any side effects.

There are several types of visual field tests, but they all have one thing in common: you look straight ahead at one point and signal when you see an object or a light somewhere off to the side.

Your provider will explain to you exactly where to look so that the test is accurate.

The two most basic types of visual field tests are very simple:

* Amsler grid: The Amsler grid is a pattern of straight lines that make perfect squares. You look at a large dot in the middle of the grid and describe any areas where the lines look blurry, wavy or broken. The Amsler grid is a quick test that only measures the middle of the visual field (your central vision) and provides your doctor with a small amount of information.

* Confrontation visual field: The term “confrontation” in this test just means that the person giving the test sits facing the person having the test, about 3 or 4 feet (around 1 meter) away. The provider holds their arms straight out to the sides. You look straight ahead, and the tester moves one hand and then the other inward toward you. You give a signal as soon as you see their hand.

The confrontation visual field test measures only the outer edge of the visual field. It’s not very exact.

Other types of visual field tests

You may hear about different types of or terms for visual field tests, including static and kinetic perimetry tests. (Perimetry test is another way of saying peripheral vision test.)

* Kinetic perimetry tests: A kinetic perimetry test is one in which the person giving the test moves an object around, and you tell them when you can see it. Providers often use the Goldmann perimetry test.

* Static perimetry tests: Automated peripheral vision tests are static perimetry tests. You look into a bowl-shaped machine and respond by pressing buttons when you see the object. Common types of static tests are the Humphrey and the Octopus.

How long does a visual field test take?

A test usually isn’t longer than about five to 10 minutes per eye.

What kind of visual field tests give more detailed information?

Computerized instruments are available to perform visual field tests and calculate results. These instruments give more reproducible and accurate results because:

* Your head is always in the same place during the test.

* The instrument has a large central “target” for you to look at, so the center of the visual field stays steady.

* The instrument uses tiny spots of light to test vision. The provider can change the brightness and color of the light to measure the sensitivity of vision at each location.

* There are clear standards for “normal” results. The instrument can compare each new test to these standards.

Results and Follow-Up:

What do the results of the visual field test mean?

A “normal” visual field test means that you can see about as well as people without vision issues.

The visual field test shows the amount of vision loss and the affected areas. The instrument prints the results as patterns of dots or numbers. The patterns tell your provider how well your eyes and visual field system work. This helps your provider diagnose an underlying health condition and what treatment you need.

A test that shows visual field loss means that vision in some areas isn’t as keen as it should be. A test could show that you have a small area of lost vision, or all vision lost in large areas.

When should I know the results of the test?

Generally, your provider should be able to give you results right away.

What are the next steps if the results are abnormal?

Abnormal results may mean different things. These results can indicate different types of issues, including glaucoma, macular degeneration or stroke. The follow-up will vary.

Your eye care provider will discuss treatment options with you.

When should I call my provider?

You should always contact your eye care provider if you have any new vision loss or eye discomfort. If you have sudden vision loss or eye pain, go to an emergency room for immediate medical help.

Additional Information

A visual field test is a diagnostic procedure that measures a person's entire field of vision, including peripheral (side) and central vision. It evaluates how well you can see in different areas of your vision and is commonly used to detect, diagnose, and monitor various eye and neurological conditions. The test plays a crucial role in identifying issues that may not be apparent during a routine eye exam, especially problems affecting peripheral vision.

Visual field testing can help uncover conditions such as glaucoma, retinal disorders, optic nerve damage, and neurological diseases like strokes or brain tumors. By mapping out the areas where vision is diminished or absent, it provides valuable insights into the health of your eyes and the visual pathways in your brain.

Importance of Test Results Interpretation

Accurate interpretation of visual field test results is critical for effective diagnosis and treatment planning. The results are presented as a detailed map showing areas where vision is normal, reduced, or absent. Key aspects of result interpretation include:

* Detection of Blind Spots: Identifying areas where vision is missing, which may indicate damage to the retina or optic nerve.

* Symmetry Analysis: Comparing the visual fields of both eyes to detect asymmetrical vision loss, which can be a sign of neurological conditions.

* Severity and Progression: Monitoring changes over time to assess the progression of diseases like glaucoma.

Patients typically receive a detailed explanation of their test results from an eye care professional, including recommendations for treatment or follow-up testing if necessary.

Uses of a Visual Field Test

Visual field tests serve a variety of purposes in both ophthalmology and neurology. Common uses include:

* Glaucoma Diagnosis and Monitoring: Identifies early signs of vision loss associated with glaucoma and tracks progression.

* Assessment of Retinal Disorders: Detects damage caused by conditions like diabetic retinopathy or retinal detachment.

* Optic Nerve Evaluation: Evaluates the health of the optic nerve, often impacted by optic neuritis or optic neuropathy.

* Neurological Conditions: Identifies vision changes due to strokes, brain tumors, or other neurological disorders.

* Pre-Surgical Planning: Assists in determining the extent of vision impairment before eye surgeries.

* Evaluation of Medication Effects: Monitors vision changes in patients taking medications that may affect eye health.

How to Prepare for a Visual Field Test

Proper preparation ensures accurate results from a visual field test. Follow these steps to get ready:

* Inform Your Eye Doctor: Share your medical history, including any eye conditions, neurological issues, or medications you are taking.

* Rest Well: Ensure you are well-rested before the test to reduce fatigue, which can affect performance.

* Wear Glasses or Contacts if Needed: Bring any corrective eyewear to the appointment, as the test may require you to wear them.

* Avoid Driving Before the Test: The procedure may involve pupil dilation, temporarily affecting your ability to drive.

* Follow Specific Instructions: Your doctor may provide additional preparation guidelines based on your individual needs.

By following these steps, you can help ensure the test provides the most accurate representation of your visual field.

What to Expect During the Procedure

A visual field test is a painless and non-invasive procedure typically performed in an eye doctor's office. Here is what what you can expect:

* Positioning: You will sit in front of a specialized machine and place your chin on a rest to stabilize your head.

* Focus on a Target: You will be asked to focus on a central point while small lights or objects appear in different parts of your visual field.

* Responding to Stimuli: You'll press a button or verbally indicate when you see the lights.

* Eye-by-Eye Testing: Each eye is tested separately by covering the other eye.

* Duration: The test typically takes 15-30 minutes to complete.

Patients can resume normal activities immediately after the test unless they have had their pupils dilated, in which case temporary visual sensitivity may occur.

Normal Range for Visual Field Test Results

Normal results indicate that your visual field is intact and free of significant blind spots beyond the natural blind spot (caused by the optic nerve head). Specific findings in a normal test include:

* Symmetrical vision between both eyes.

* Full peripheral vision within the expected range for your age.

* No unexplained areas of vision loss or distortion.

* Abnormal results may require further investigation to determine the underlying cause and develop an appropriate treatment plan.

Benefits of a Visual Field Test

Visual field testing offers numerous benefits for maintaining eye and neurological health. These include:

* Early Detection: Identifies vision problems before noticeable symptoms develop.

* Comprehensive Assessment: Provides a detailed map of your visual capabilities.

* Monitoring Disease Progression: Tracks changes in vision over time for conditions like glaucoma.

* Guiding Treatment Decisions: Helps tailor treatments based on the specific pattern of vision loss.

* Preventing Vision Loss: Enables timely interventions to preserve remaining vision.

Limitations and Risks of a Visual Field Test

While visual field testing is highly beneficial, it has certain limitations and risks:

* False Positives or Negatives: Patient fatigue or inattention can lead to inaccurate results.

* Limited Scope: Does not provide detailed images of the eyes' internal structures.

* Temporary Discomfort: Prolonged focus during the test may cause mild eye strain.

* Not a Standalone Diagnostic Tool: Often combined with other tests for a complete evaluation.

Understanding these limitations can help set realistic expectations for the procedure.

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs) About Visual Field Tests:

1. Why is a visual field test important?

A visual field test is essential for detecting early signs of eye and neurological conditions, including glaucoma and optic nerve damage. It provides a detailed map of your field of vision, allowing doctors to diagnose problems that may not be noticeable during routine eye exams. Early detection through this test helps prevent further vision loss by enabling timely treatment and monitoring.

2. How often should I get a visual field test?

The frequency of visual field testing depends on your age, medical history, and risk factors. People with glaucoma or other eye conditions may need regular testing every 6-12 months. For routine eye health, adults should have a visual field test every 1-2 years as part of a comprehensive eye exam. Consult your doctor for personalized recommendations.

3. Is the visual field test painful?

No, the visual field test is completely painless and non-invasive. It involves sitting comfortably and responding to visual stimuli. Some patients may find it slightly tiring to maintain focus during the test, but there is no physical discomfort involved.

4. What do abnormal visual field test results mean?

Abnormal results indicate areas of reduced or missing vision, which could be caused by glaucoma, retinal conditions, optic nerve damage, or neurological issues like strokes. Your doctor will interpret the results and may recommend additional tests to determine the cause and guide treatment.

5. Can children undergo a visual field test?

Yes, children can undergo visual field testing if recommended by their doctor. The procedure is modified to suit their age and ability to follow instructions. It is often used to diagnose conditions like optic nerve disorders or monitor vision changes caused by neurological issues in children.

6. What is the difference between central and peripheral vision testing?

Central vision testing evaluates the ability to see details in the center of your vision, while peripheral vision testing assesses your ability to detect objects and movement in the outer areas of your field of vision. Visual field tests often include both types to provide a complete assessment.

7. Can a visual field test detect brain tumors?

Yes, a visual field test can help detect vision changes caused by brain tumors. Tumors affecting the optic pathways or visual centers in the brain can cause specific patterns of vision loss, which are identifiable through this test. Further imaging tests may be required for confirmation.

8. How accurate is a visual field test?

Visual field tests are highly accurate when performed correctly and under optimal conditions. Factors like patient attentiveness and proper calibration of the equipment influence the reliability of the results. Repeat testing may be necessary to confirm findings.

9. Are there alternatives to a visual field test?

Alternatives include fundus photography, optical coherence tomography (OCT), and perimetry tests. Each method has unique applications, and your doctor will choose the most appropriate one based on your condition and diagnostic needs.

10. What should I do if I fail a visual field test?

Failing a visual field test doesn’t always mean permanent vision loss. It indicates areas requiring further investigation. Follow your doctor’s recommendations for additional testing or treatment. Early intervention can often prevent further deterioration and improve outcomes.

Conclusion

The visual field test is an invaluable diagnostic tool for assessing and preserving eye and neurological health. By identifying early signs of vision loss and guiding treatment decisions, it plays a vital role in managing conditions like glaucoma and neurological disorders. While the procedure has certain limitations, its benefits in early detection and monitoring far outweigh them. Regular visual field testing, combined with comprehensive eye care, can help maintain optimal vision and quality of life. Consult your eye doctor to learn more about this important test and how it fits into your overall health plan.

#6 Science HQ » Arthritis » Yesterday 17:15:40

- Jai Ganesh

- Replies: 0

Arthritis

Gist

Arthritis is inflammation of one or more joints, causing pain, stiffness, and swelling. Common types include osteoarthritis (wear-and-tear) and rheumatoid arthritis (autoimmune). Key risk factors include age, genetics, and obesity. Treatments include medications, physical therapy, and lifestyle changes, aiming to manage symptoms and improve function.

Good approaches for arthritis include low-impact exercise, weight management, heat/cold therapy, and an anti-inflammatory diet rich in fruits, vegetables, fish, and whole grains, while avoiding processed foods and sugar, alongside potential medications, physical therapy, and sometimes surgery for severe cases, with lifestyle changes being key. Balancing activity and rest, maintaining good posture, and using assistive devices can also significantly ease symptoms.

Summary

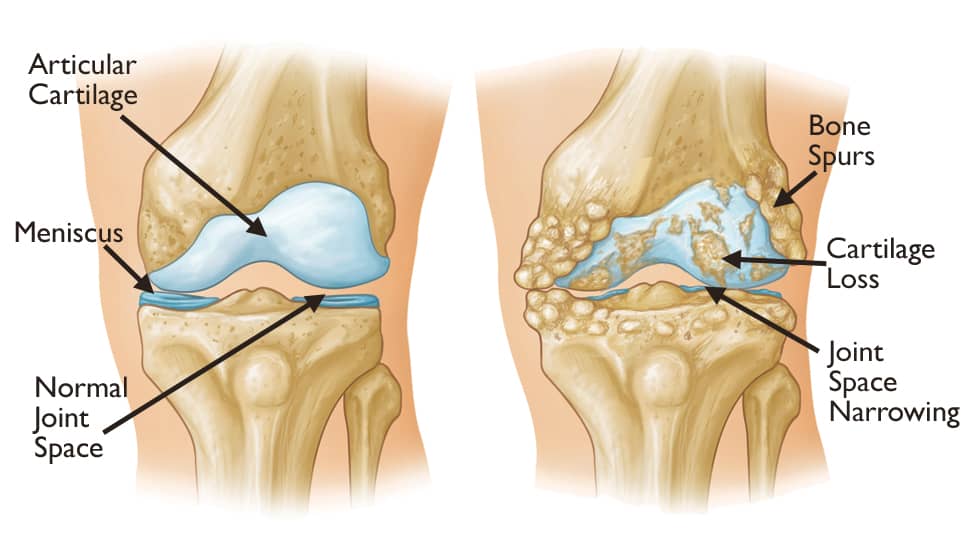

Arthritis is a general medical term used to describe a disorder in which the smooth cartilagenous layer that lines a joint is lost, resulting in bone grinding on bone during joint movement. Symptoms generally include joint pain and stiffness. Other symptoms may include redness, warmth, swelling, and decreased range of motion of the affected joints. In certain types of arthritis, other organs, such as the skin, are also affected. Onset can be gradual or sudden.

There are several types of arthritis. The most common forms are osteoarthritis (most commonly seen in weightbearing joints) and rheumatoid arthritis. Osteoarthritis usually occurs as a person ages and often affects the hips, knees, shoulders, and fingers. Rheumatoid arthritis is an autoimmune disorder that often affects the hands and feet. Other types of arthritis include gout, lupus, and septic arthritis. These are inflammatory based types of rheumatic disease.

Early treatment for arthritis commonly includes resting the affected joint and conservative measures such as heating or icing. Weight loss and exercise may also be useful to reduce the force across a weightbearing joint. Medication intervention for symptoms depends on the form of arthritis. These may include anti-inflammatory medications such as ibuprofen and paracetamol (acetaminophen). With severe cases of arthritis, joint replacement surgery may be necessary.

Osteoarthritis is the most common form of arthritis affecting more than 3.8% of people, while rheumatoid arthritis is the second most common affecting about 0.24% of people. In Australia about 15% of people are affected by arthritis, while in the United States more than 20% have a type of arthritis. Overall arthritis becomes more common with age. Arthritis is a common reason people are unable to carry out their work and can result in decreased ability to complete activities of daily living. The term arthritis is derived from arthr- (meaning 'joint') and -itis (meaning 'inflammation').

Details:

Overview

Arthritis and other rheumatic diseases are common conditions that cause pain, swelling, and limited movement. They affect joints and connective tissues around the body. Millions of people in the U.S. have some form of arthritis.

Arthritis means redness and swelling (inflammation) of a joint. A joint is where 2 or more bones meet. There are more than 100 different arthritis diseases. Rheumatic diseases include any condition that causes pain, stiffness, and swelling in joints, muscles, tendons, ligaments, or bones. Arthritis is usually ongoing (chronic).

Arthritis and other rheumatic diseases are more common in women than men. These conditions are often found in older people. But people of all ages may be affected.

The 2 most common forms of arthritis are:

* Osteoarthritis. This is the most common type of arthritis. It is a chronic disease of the joints, especially the weight-bearing joints of the knee, hip, and spine. It destroys the padding on the ends of bones (cartilage) and narrows the joint space. It can also cause bone overgrowth, bone spurs, and reduced function. It occurs in most people as they age. It may also occur in young people from an injury or overuse.

* Rheumatoid arthritis. This is an autoimmune disease that causes inflammation in the joint linings. The inflammation may affect all the joints. It can also affect organs, such as the heart or lungs.

Other forms of arthritis or related disorders include:

* Gout. This condition causes uric acid crystals to build up in small joints, such as the big toe. It causes pain and inflammation.

* Lupus. This is a chronic autoimmune disorder. It causes periods of inflammation and damage in joints, tendons, and organs.

* Scleroderma. This autoimmune disease causes thickening and hardening of the skin and other connective tissue in the body.

* Ankylosing spondylitis. This form of arthritis causes inflammation of the spinal joints. It may lead to severe chronic pain and discomfort. In more advanced cases, sections of the bones fuse together in an immobile position. It can also cause inflammation in other parts of the body. Though it primarily affects the spine, it can also affect the shoulders, hips, ribs, and the small joints of the hands and feet.

* Juvenile idiopathic arthritis or juvenile rheumatoid arthritis. This is a form of arthritis in children under the age of 16 that causes inflammation and joint stiffness. Children may have symptoms that last a limited time, such as a few months or years or in some cases a lifetime. Getting diagnosed and treated early may help prevent joint damage.

What causes arthritis?

The cause depends on the type of arthritis. Osteoarthritis is caused by wear and tear of the joint over time or because of overuse. Rheumatoid arthritis, lupus, and scleroderma are caused by the body’s immune system attacking the body’s own tissues. Gout is caused by the buildup of crystals in the joints. Some forms of arthritis can be linked to genes. People with genetic marker HLA-B27 have a higher risk for ankylosing spondylitis. For some other forms of arthritis, the cause is not known.

Who is at risk for arthritis?

Some risk factors for arthritis that can’t be changed include:

* Age. The older you are, the more likely you are to have arthritis.

* Gender. Women are more likely to have arthritis than men.

* Heredity. Some types of arthritis are linked to certain genes.

Risk factors that may be changed include:

* Weight. Being overweight or obese can damage your knee joints. This can make them more likely to develop osteoarthritis.

* Injury. A joint that has been damaged by an injury is more likely to develop arthritis at some point.

* Infection. Reactive arthritis can affect joints after an infection.

* Your job. Work that involves repeated bending or squatting can lead to knee arthritis.

What are the symptoms of arthritis?

Each person’s symptoms may vary. The most common symptoms include:

* Pain in 1 or more joints that doesn’t go away, or comes back.

* Warmth and redness in 1 or more joints.

* Swelling in 1 or more joints.

* Stiffness in 1 or more joints.

* Trouble moving 1 or more joints in a normal way.

These symptoms can look like other health conditions. Always see your health care provider for a diagnosis.

How is arthritis diagnosed?

Your provider will take your medical history and give you a physical exam. Tests may also be done. These include blood tests, such as:

* Antinuclear antibody test. This checks antibody levels in the blood.

* Complete blood count. This checks if your white blood cell, red blood cell, and platelet levels are normal.

* Creatinine. This test checks for kidney disease.

* Sedimentation rate. This test can find inflammation.

* Hematocrit. This test measures the number of red blood cells.

* RF (rheumatoid factor) and CCP (cyclic citrullinated peptide) antibody tests. These can help diagnose rheumatoid arthritis.

* White blood cell count. This checks the level of white blood cells in your blood.

* Uric acid. This helps diagnose gout.

Other tests may be done, such as:

* Joint aspiration (arthrocentesis). A small sample of synovial fluid is taken from a joint. It's tested to see if crystals or bacteria are present.

* X-rays or other imaging tests. These can tell how damaged a joint is.

* Urine test. This checks for protein and different kinds of blood cells.

* HLA tissue typing. This looks for genetic markers of ankylosing spondylitis.

* Skin biopsy. Tiny tissue samples are removed and checked under a microscope. This test helps to diagnose a type of arthritis that involves the skin, such as lupus or psoriatic arthritis.

* Muscle biopsy. Tiny tissue samples are removed and checked under a microscope. This test helps to diagnose conditions that affect muscles.

How is arthritis treated?

Treatment will depend on your symptoms, your age, and your general health. It will also depend on what type of arthritis you have and how bad the condition is. A treatment plan is tailored to each person with their provider.

There is no known cure for arthritis. The goal of treatment is often to limit pain and inflammation and to help the joint work. Treatment plans often use both short-term and long-term methods.

Short-term treatments include:

* Medicines. Short-term relief for pain and inflammation may include pain relievers, such as acetaminophen, aspirin, ibuprofen, or other nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory medicines.

* Heat and cold. Pain may be eased by using moist heat (warm bath or shower) or dry heat (heating pad) on the joint. Pain and swelling may be eased with cold (ice pack wrapped in a thin towel) on the joint.

* Joint immobilization. Using a splint or brace can help a joint rest and protect it from more injury.

* Massage. Lightly massaging painful muscles may increase blood flow and bring warmth to the muscle.

* Transcutaneous electrical nerve stimulation (TENS). Pain may be eased with a TENS device. The device sends mild, electrical pulses to nerve endings in the painful area. This blocks pain signals to the brain and changes how you feel pain.

* Acupuncture. Thin needles are inserted at certain points in the body. It may help the release of natural pain-relieving chemicals made by the nervous system. The procedure is done by a licensed provider.

Long-term treatments include:

* Disease-modifying antirheumatic drugs. These prescription medicines may slow down the disease and treat any immune system problems linked to the disease. Examples of these medicines include methotrexate, hydroxychloroquine, sulfasalazine, and chlorambucil.

* Corticosteroids. Corticosteroids reduce inflammation and swelling. These medicines, such as prednisone, can be taken by mouth (orally) or as a shot.

* Hyaluronic acid therapy. This is a joint fluid that appears to break down in people with osteoarthritis. It can be injected into a joint, such as the knee to help ease symptoms.

* Surgery. There are many types of surgery, depending on which joints are affected. Surgery may include arthroscopy, fusion, or joint replacement. Full recovery after surgery may take up to 6 months. A rehabilitation program after surgery is an important part of the treatment.

Arthritis treatment can include a team of health care providers, such as:

* Orthopedist or orthopedic surgeon.

* Rheumatologist.

* Physiatrist.

* Primary care (family medicine or internal medicine).

* Rehabilitation nurse.

* Dietitian.

* Physical therapist.

* Occupational therapist.

* Social worker.

* Psychologist or psychiatrist.

* Recreational therapist.

* Vocational therapist.

What are possible complications of arthritis?

Because arthritis causes joints to get worse over time, it can cause disability. It can cause pain and movement problems. You may be less able to carry out normal daily activities and tasks.

Living with arthritis

There is no known cure for arthritis. But it’s important to help keep joints working by reducing pain and inflammation. Work on a treatment plan with your provider that includes medicine and therapy. Work on lifestyle changes that can improve your quality of life. Lifestyle changes include:

* Weight loss. Extra weight puts more stress on weight-bearing joints, such as the hips and knees.

* Exercise. Some exercises may help reduce joint pain and stiffness. These include swimming, walking, low-impact aerobic exercise, and range-of-motion exercises. Stretching exercises may also help keep the joints flexible.

* Activity and rest. To reduce stress on your joints, switch between activity and rest. This can help protect your joints and reduce your symptoms.

* Using assistive devices. Canes, crutches, and walkers can help keep stress off certain joints and improve balance. Make sure walkers, canes, and other mobility devices are adjusted to meet your height and posture.

* Using adaptive equipment. Resachers and grabbers let you extend your reach and reduce straining. Dressing aids help you get dressed more easily.

* Managing use of medicines. Long-term use of some anti-inflammatory medicines can lead to stomach bleeding and other possible side effects. Work with your to create a plan to reduce this risk and manage your pain.

When to contact your doctor

Contact your if you have questions about your medicines, your symptoms get worse, or you have new symptoms.

Additional Information

Arthritis is extremely common, especially in people older than 50. It causes joint pain, stiffness and inflammation. Your provider will help you understand which type of arthritis you have, what’s causing it and which treatments you’ll need. You may need a joint replacement if you have severe arthritis that you can’t manage with other treatments.

Overview:

What is arthritis?

Arthritis is a disease that causes damage in your joints. Joints are places in your body where two bones meet.

Some joints naturally wear down as you age. Lots of people develop arthritis after that normal, lifelong wear and tear. Some types of arthritis happen after injuries that damage a joint. Certain health conditions also cause arthritis.

Arthritis can affect any joint, but is most common in people’s:

* Hands and wrists.

* Knees.

* Hips.

* Feet and ankles.

* Shoulders.

* Lower back (lumbar spine).

A healthcare provider will help you find ways to manage symptoms like pain and stiffness. Some people with severe arthritis eventually need surgery to replace their affected joints.

Visit a healthcare provider if you’re experiencing joint pain that’s severe enough to affect your daily routine or if it feels like you can’t move or use your joints as well as usual.

Types of arthritis

There are more than 100 different types of arthritis. Some of the most common types include:

* Osteoarthritis: Wear and tear arthritis.

* Rheumatoid arthritis: Arthritis that happens when your immune system mistakenly damages your joints.

* Gout: Arthritis that causes sharp uric acid crystals to form in your joints.

* Ankylosing spondylitis: Arthritis that affects joints near your lower back.

* Psoriatic arthritis: Arthritis that affects people who have psoriasis.

* Juvenile arthritis: Arthritis in kids and teens younger than 16.

Depending on which type of arthritis you have, it can break down the natural tissue in your joint (degeneration) or cause inflammation (swelling). Some types cause inflammation that leads to degeneration.

How common is arthritis?

Arthritis is extremely common. Experts estimate that more than one-third of Americans have some degree of arthritis in their joints.

Osteoarthritis is the most common type. Studies have found that around half of all adults will develop osteoarthritis at some point.

Symptoms and Causes

There are more than 100 types of arthritis, but they share several common signs and symptoms.

The most common signs and symptoms of arthritis usually affect your joints and your ability to use them.

What are arthritis symptoms and signs?

The most common arthritis symptoms and signs include:

* Joint pain.

* Stiffness or reduced range of motion (how far you can move a joint).

* Swelling (inflammation).

* Skin discoloration.

* Tenderness or sensitivity to touch around a joint.

* A feeling of heat or warmth near your joints.

Where you experience symptoms depends on which type of arthritis you have, and which of your joints it affects.

Some types of arthritis cause symptoms in waves that come and go called flares or flare-ups. Others make your joints feel painful or stiff all the time, or after being physically active.

What is the main cause of arthritis?

What causes arthritis varies depending on which type you have:

* Osteoarthritis happens naturally as you age — a lifetime of using your joints can eventually wear down their cartilage cushioning.

* You may develop gout if you have too much uric acid in your blood (hyperuricemia).

* Your immune system can cause arthritis (including rheumatoid arthritis) when it damages your joints by mistake.

* Certain viral infections (including COVID-19) can trigger viral arthritis.

* Sometimes, arthritis happens with no cause or trigger. Providers call this idiopathic arthritis.

What are the risk factors?

Anyone can develop arthritis, but some factors may make you more likely to, including:

* Tobacco use: Smoking and using other tobacco products increases your risk.

* Family history: People whose biological family members have arthritis are more likely to develop it.

* Activity level: You might be more likely to have arthritis if you aren’t physically active regularly.

* Other health conditions: Having autoimmune diseases, obesity or any condition that affects your joints increases the chances you’ll develop arthritis.

Some people have a higher arthritis risk, including:

* People older than 50.

* Females.

* Athletes, especially those who play contact sports.

* People who have physically demanding jobs or do work that puts a lot of stress on their joints (standing, crouching, being on your hands and knees for a long time, etc.).

At what age does arthritis usually start?

Arthritis can develop at any age. When it starts depends on which type you have and what’s causing it.

In general, osteoarthritis affects adults older than 50. Rheumatoid arthritis usually develops in adults age 30 to 60.

Other types that have a more direct cause usually start closer to that specific trigger. For example, people with post-traumatic arthritis don’t develop it until after their joints are injured, and gout doesn’t develop until after you’ve had high uric acid levels for at least several months.

Talk to a healthcare provider about your unique arthritis risk, and when you should start watching for signs or changes in your joints.

Diagnosis and Tests:

How do healthcare providers diagnose arthritis?

A healthcare provider will diagnose arthritis with a physical exam. They’ll examine your affected joints and ask about your symptoms. Tell your provider when you first noticed symptoms like pain and stiffness, and if any activities or times of day make them worse.

Your provider will probably check your range of motion (how far you can move a joint). They may compare one joint’s range of motion to other, similar joints (your other knee, ankle or fingers, for example).

Arthritis tests

Your provider might use imaging tests to take pictures of your joints, including:

* X-ray.

* Ultrasound.

* Magnetic resonance imaging (MRI).

* A computed tomography (CT) scan.

These tests can help your provider see damage inside your joints. They can also help your provider rule out other injuries or issues that might cause similar symptoms, like bone fractures (broken bones).

Your provider may use blood tests to check your uric acid levels if they think you have gout. Blood tests can also show signs of infections or autoimmune diseases.

Management and Treatment:

What is arthritis treatment?

There’s no cure for arthritis, but your healthcare provider will help you find treatments that manage your symptoms. Which treatments you’ll need depend on what’s causing the arthritis, which type you have and which joints it affects.

The most common arthritis treatments include:

* Over-the-counter (OTC) anti-inflammatory medicine like NSAIDs or acetaminophen.

* Corticosteroids (prescription anti-inflammatory medicine, including cortisone shots).

* Disease-modifying antirheumatic drugs (DMARDs) if you have rheumatoid or psoriatic arthritis.

* Physical therapy or occupational therapy can help you improve your strength, range of motion and confidence while you’re moving.

* Surgery (usually only if nonsurgical treatments don’t relieve your symptoms).

Arthritis surgery

You may need surgery if you have severe arthritis and other treatments don’t work. The two most common types of arthritis surgery are joint fusion and joint replacement.

Joint fusion is exactly what it sounds like: surgically joining bones together. It’s most common for bones in your spine (spinal fusion) or your ankle (ankle fusion).

If your joints are damaged or you’ve experienced bone loss, you might need an arthroplasty (joint replacement). Your surgeon will remove your damaged natural joint and replace it with a prosthesis (artificial joint). You might need a partial or total joint replacement.

Your provider or surgeon will tell you which type of surgery you’ll need and what to expect.

Outlook / Prognosis:

What can I expect if I have arthritis?

You should expect to manage arthritis symptoms for a long time (probably the rest of your life). Your provider will help you find treatments that reduce how much (and how often) arthritis impacts your daily routine.

Some people with arthritis experience more severe symptoms as they age. Ask your provider how often you should have follow-up visits to check for changes in your joints.

#7 Re: Jai Ganesh's Puzzles » General Quiz » Yesterday 15:58:08

Hi,

#10789. What does the term in Biology Ichthyology mean?

#10790. What does the term in Biology Immune response mean?

#8 Re: Jai Ganesh's Puzzles » English language puzzles » Yesterday 15:44:22

Hi,

#5995. What does the noun newscast mean?

#5996. What does the noun newsreel mean?

#9 Re: Jai Ganesh's Puzzles » Doc, Doc! » Yesterday 15:35:48

Hi,

#2594. What does the medical term Levator scapulae muscle mean?

#10 Re: Jai Ganesh's Puzzles » 10 second questions » Yesterday 15:00:37

Hi,

#9880.

#11 Re: Jai Ganesh's Puzzles » Oral puzzles » Yesterday 14:50:19

Hi,

#6373.

#12 Re: Exercises » Compute the solution: » Yesterday 14:22:27

Hi,

2734.

#13 Re: This is Cool » Miscellany » Yesterday 00:06:36

2520) Fathometer

Gist

A fathometer is a specialized sonar-based instrument used to measure the depth of water (bathymetry) by calculating the time it takes for a sound wave to travel from the surface to the bottom and return as an echo. It is primarily used for navigation, mapping the seafloor, identifying fish, and checking ice thickness.

What is a fathometer used for measuring?

A fathometer is a device that measures the depth of water by measuring the time it takes for a sound wave to travel from the surface to the bottom and for its echo to be returned.

Summary

“A fathometer is a device that measures the depth of water by measuring the time it takes for a sound wave to travel from the surface to the bottom and for its echo to be returned.”

“Echo sounding or depth sounding is the use of sonar for ranging, normally to determine the depth of water (bathymetry). It involves transmitting acoustic waves into water and recording the time interval between emission and return of a pulse; the resulting time of flight, along with knowledge of the speed of sound in water, allows determining the distance between sonar and target. This information is then typically used for navigation purposes or in order to obtain depths for charting purposes.”

Had the fathometer, or echo sounder, been available, it might have changed maritime warfare during the First World War. The Fathometer, first offered for sale in 1923, uses sound waves to quickly and accurately determine water depth and detect underwater objects, like submarines. Before echo sounders, sailors dropped and retrieved weighted hand-held lines (lead lines) to estimate water depth. After the sinking of Titanic in 1912, Canadian engineer Reginald A. Fessenden wanted to improve underwater object detection and communications. An expert in wireless radio technology, Fessenden built an electromagnetic device, called the oscillator, which produced underwater sound waves. These waves bounced off objects and, by measuring the echoes produced by the returning waves, users could estimate the position of the object. Tests in 1914 proved the oscillator could not only detect icebergs, but also determine water depth. Fessenden urged war planners to use the oscillator as a submarine detector, but with his prickly personality, he was rebuffed. After the war, the Submarine Signal Company of Boston incorporated Fessenden’s oscillator technology in the fathometer, opening a new era of navigation, subsurface detection, and marine mapping.

Herbert Grove Dorsey (April 24, 1876 – 1961) was an American engineer, inventor and physicist. He was principal engineer of the United States Coast and Geodetic Survey Radio sonic Laboratory in the 1930s. He invented the first practical fathometer, a water depth measuring instrument for ships.

The depth of the ocean is calculated by knowing how fast sound travels in the water (approximately 1,500 meters per second). This method of seafloor mapping is called echo sounding. … Water depth is typically measured by echo sounders that transmit sound at 12 kilohertz (kHz).

Depth finder, also called echo sounder, device used on ships to determine the depth of water by measuring the time it takes a sound (sonic pulse) produced just below the water surface to return, or echo, from the bottom of the body of water. … sonar devices are used to measure the depth of sea.

Details

A fathometer is a device that measures the depth of water by measuring the time it takes for a sound wave to travel from the surface to the bottom and for its echo to be returned.

A Fathometer is used in ocean sounding when the depth of water is considerably deep and keeps a continuous and precise record of the depth of water under the boat or ship on which it is placed. It is an echo-sounding device in which water depths are determined by measuring the time it takes for vibrations produced by sound waves to travel from a location near the top of the water to the bottom and back. Depending on the kind of water being utilised, it is calibrated to read depth in line with the velocity of sound in that water. A fathometer may either visually represent the depth of the water or graphically indicate the depth of the water on a roll that is continually rotating and can produce a virtual profile of that water body. The fathometer meaning is derived from the word fathom. Fathom is a unit of water depth. Herbert Grove Dorsey invented and patented the first practical fathometer in 1928.

Working of fathometer

Fathometer working is quite simple and accurate compared to older methods of distance measuring of water bodies like the lead lines. A fathometer contains the following parts:

1. Transmitting and receiving oscillators ( for sending and receiving the sound waves )

2. Recorder unit ( for the recording of data)

3. Transmitter / Power unit. (power supply)

The distance between the signal’s leaving pulse and its return is calculated by multiplying half of the time between the signal’s outgoing pulse and its return by the sound speed in the water, roughly 1.5 kilometres per second. When using echo-sounding for precise applications such as hydrography, it is necessary to measure the sound speed, which is commonly accomplished by submerging a sound velocity probe into the water. Echo sounding is a special-purpose use of sonar that is used to find the bottom of any water bodies.

The Fessenden Fathometer was one of the earliest commercial echo- machines, and it made use of the Fessenden oscillator to create sound waves. Submarine Signal Company fitted this for the first time aboard the M&M liner S.S. Berkshire in 1924.

The fathometer is more accurate because it obtains a sounding that is exactly vertical. The vessel’s speed causes it to diverge significantly from the vertical. The precision of 7.5 cm is possible in ports and harbours when the water is at normal levels and conditions. When there is a strong current, and the weather is not conducive to taking soundings with the lead line, a fathometer may be employed (an Old device to measure the depth of water). The fathometer has a higher sensitivity than the lead line.

Uses of fathometer

1. Fathometer echo sounding is a technique that is often employed in fishing. Variations in elevation are often associated with areas where fish gather. In addition, schools of fish will be recorded. Fishfinder is an echo-sounding instrument, similar to a fathometer, that is used by both recreational and commercial fishermen to locate fish and other marine life.

2. This fathometer is installed on almost all ships and submarines in order to get an idea of the depth of water bodies and the morphology of rocks and seabeds in the area surrounding the ships and submarines.

3. It may also be used to measure the rise and fall of the tides in areas where the water is shallow.

4. The lead line is also one of the techniques for measuring the depth of water bodies, but it takes time and cannot be used in bad weather, so it has limited applications. The fathometer, on the other hand, can be used in bad weather and provides a more accurate result in a shorter period of time, making it more useful.

5. The same technique as the fathometer is used to send out sonic pulses in order to identify underwater things.

6. When it comes to submarines, a fathometer is quite important. Along with shoal water protection, other peacetime applications include identifying fish, assessing the thickness of ice in Arctic areas, and mapping the ocean’s surface.

7. A fathometer, also known as a Sonic depth finder, may be used to create a profile of the ocean bottom by recording thousands of soundings each hour over a long period of time. The use of echo sounders in oceanography and survey work to locate underwater pinnacles and shoals is common practice among hydrographers.

Conclusion

A fathometer is a device that uses echo sounding to measure the depth of the ocean or any other water bodies. Fathom is the unit for measuring the depth of any water body. A fathometer is more useful compared to conventional instruments to measure the depth because it can be used in bad weather and is more accurate with only an error of ± 7 cm. A fathometer is also used to locate the iceberg below the sea surface and schools of fish.

Additional Information

A Fathometer is used in ocean sounding where the depth of water is too much, and to make a continuous and accurate record of the depth of water below the boat or ship at which it is installed. It is an echo-sounding instrument in which water depths are obtained be determining the time required for the sound waves to travel from a point near the surface of the water to the bottom and back. It is adjusted to read depth on accordance with the velocity of sound in the type of water in which it is being used. A fathometer may indicate the depth visually or indicate graphically on a roll which continuously goes on revolving and provide a

virtual profile of the lake or sea.

What are the components of echo sounding instrument?

The main parts of an echo-sounding apparatus are:

1. Transmitting and receiving oscillators.

2. Recorder unit.

3. Transmitter / Power unit.

It consists in recording the interval of time between the emission of a sound impulse direct to the bottom of the sea and the reception of the wave or echo, reflected from the bottom. If the speed of sound in that water is v and the time interval between the transmitter and receiver is t, the depth h is given by

h = ½ vt

…

Due to the small distance between the receiver and the transmitter, a slight correction is necessary in shallow waters. The error between the true depth and the recorded depth can be calculated very easily by simple geometry. If the error is plotted against the recorded depth, the true depth can be easily known. The recording of the sounding is produced by the action of a small current passing through chemically impregnated paper from a rotating stylus to an anode plate. The stylus is fixed at one end of a radial arm which revolves at constant speed. The stylus makes a record on the paper at the instants when the sound impulse is transmitted and when the echo returns to the receiver.

Advantage of echo-sounding

Echo-sounding has the following advantages over the older method of lead line and rod:

1. It is more accurate as a truly vertical sounding is obtained. The speed of the vessel does deviate it appreciably from the vertical. Under normal water conditions, in ports and harbors an accuracy of 7.5 cm may be obtained.