Math Is Fun Forum

You are not logged in.

- Topics: Active | Unanswered

Pages: 1

#1 2023-08-19 18:56:09

- Jai Ganesh

- Administrator

- Registered: 2005-06-28

- Posts: 52,724

Epilepsy

Epilepsy

Gist

Epilepsy is a disorder of the brain characterized by repeated seizures. A seizure is usually defined as a sudden alteration of behavior due to a temporary change in the electrical functioning of the brain. Normally, the brain continuously generates tiny electrical impulses in an orderly pattern.

Summary

Epilepsy is a group of non-communicable neurological disorders characterized by recurrent epileptic seizures. An epileptic seizure is the clinical manifestation of an abnormal, excessive, purposeless and synchronized electrical discharge in the brain cells called neurons. The occurrence of two or more unprovoked seizures defines epilepsy. The occurrence of just one seizure may warrant the definition (set out by the International League Against Epilepsy) in a more clinical usage where recurrence may be able to be prejudged. Epileptic seizures can vary from brief and nearly undetectable periods to long periods of vigorous shaking due to abnormal electrical activity in the brain. These episodes can result in physical injuries, either directly such as broken bones or through causing accidents. In epilepsy, seizures tend to recur and may have no immediate underlying cause. Isolated seizures that are provoked by a specific cause such as poisoning are not deemed to represent epilepsy. People with epilepsy may be treated differently in various areas of the world and experience varying degrees of social stigma due to the alarming nature of their symptoms.

The underlying mechanism of an epileptic seizure is excessive and abnormal neuronal activity in the cortex of the brain which can be observed in the electroencephalogram (EEG) of an individual. The reason this occurs in most cases of epilepsy is unknown (cryptogenic); some cases occur as the result of brain injury, stroke, brain tumors, infections of the brain, or birth defects through a process known as epileptogenesis. Known genetic mutations are directly linked to a small proportion of cases. The diagnosis involves ruling out other conditions that might cause similar symptoms, such as fainting, and determining if another cause of seizures is present, such as alcohol withdrawal or electrolyte problems. This may be partly done by imaging the brain and performing blood tests. Epilepsy can often be confirmed with an EEG, but a normal test does not rule out the condition.

Epilepsy that occurs as a result of other issues may be preventable. Seizures are controllable with medication in about 69% of cases; inexpensive anti-seizure medications are often available. In those whose seizures do not respond to medication; surgery, neurostimulation or dietary changes may then be considered. Not all cases of epilepsy are lifelong, and many people improve to the point that treatment is no longer needed.

As of 2020, about 50 million people have epilepsy. Nearly 80% of cases occur in the developing world. In 2015, it resulted in 125,000 deaths, an increase from 112,000 in 1990. Epilepsy is more common in older people. In the developed world, onset of new cases occurs most frequently in babies and the elderly. In the developing world, onset is more common at the extremes of age – in younger children and in older children and young adults due to differences in the frequency of the underlying causes. About 5–10% of people will have an unprovoked seizure by the age of 80, with the chance of experiencing a second seizure rising to between 40% and 50%. In many areas of the world, those with epilepsy either have restrictions placed on their ability to drive or are not permitted to drive until they are free of seizures for a specific length of time. The word epilepsy is from Ancient Greek "to seize, possess, or afflict".

Details:

Key facts

* Epilepsy is a chronic noncommunicable disease of the brain that affects people of all ages.

* Around 50 million people worldwide have epilepsy, making it one of the most common neurological diseases globally.

* Nearly 80% of people with epilepsy live in low- and middle-income countries.

* It is estimated that up to 70% of people living with epilepsy could live seizure-free if properly diagnosed and treated.

* The risk of premature death in people with epilepsy is up to three times higher than for the general population.

* Three quarters of people with epilepsy living in low-income countries do not get the treatment they need.

* In many parts of the world, people with epilepsy and their families suffer from stigma and discrimination.

Overview

Epilepsy is a chronic noncommunicable disease of the brain that affects around 50 million people worldwide. It is characterized by recurrent seizures, which are brief episodes of involuntary movement that may involve a part of the body (partial) or the entire body (generalized) and are sometimes accompanied by loss of consciousness and control of bowel or bladder function.

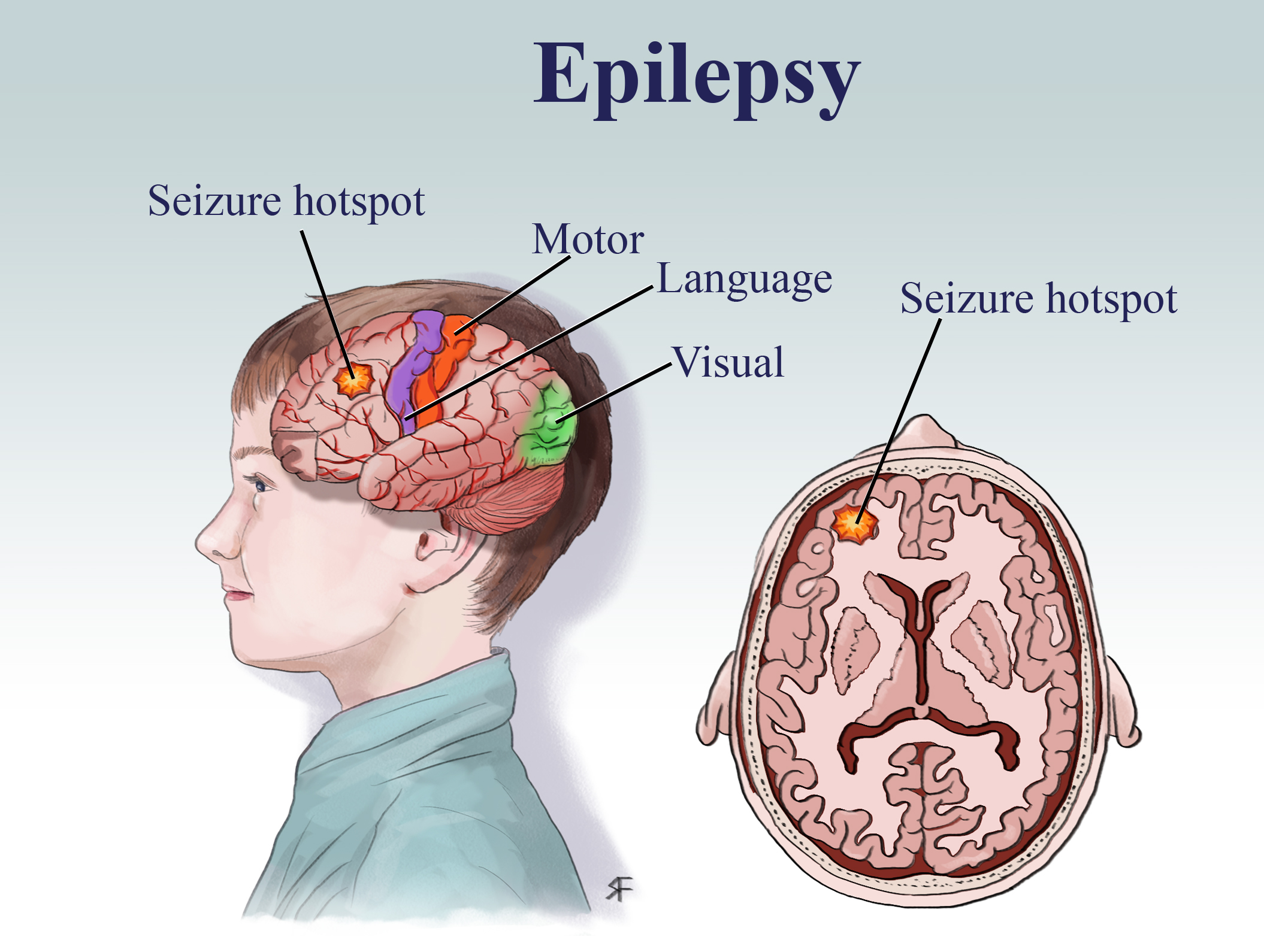

Seizure episodes are a result of excessive electrical discharges in a group of brain cells. Different parts of the brain can be the site of such discharges. Seizures can vary from the briefest lapses of attention or muscle jerks to severe and prolonged convulsions. Seizures can also vary in frequency, from less than one per year to several per day.

One seizure does not signify epilepsy (up to 10% of people worldwide have one seizure during their lifetime). Epilepsy is defined as having two or more unprovoked seizures. Epilepsy is one of the world’s oldest recognized conditions, with written records dating back to 4000 BCE. Fear, misunderstanding, discrimination and social stigma have surrounded epilepsy for centuries. This stigma continues in many countries today and can impact on the quality of life for people with the disease and their families.

Signs and symptoms

Characteristics of seizures vary and depend on where in the brain the disturbance first starts, and how far it spreads. Temporary symptoms occur, such as loss of awareness or consciousness, and disturbances of movement, sensation (including vision, hearing and taste), mood, or other cognitive functions.

People with epilepsy tend to have more physical problems (such as fractures and bruising from injuries related to seizures), as well as higher rates of psychological conditions, including anxiety and depression. Similarly, the risk of premature death in people with epilepsy is up to three times higher than in the general population, with the highest rates of premature mortality found in low- and middle-income countries and in rural areas.

A great proportion of the causes of death related to epilepsy, especially in low- and middle-income countries, are potentially preventable, such as falls, drowning, burns and prolonged seizures.

Rates of disease

Epilepsy accounts for a significant proportion of the world’s disease burden, affecting around 50 million people worldwide. The estimated proportion of the general population with active epilepsy (i.e. continuing seizures or with the need for treatment) at a given time is between 4 and 10 per 1000 people.

Globally, an estimated 5 million people are diagnosed with epilepsy each year. In high-income countries, there are estimated to be 49 per 100 000 people diagnosed with epilepsy each year. In low- and middle-income countries, this figure can be as high as 139 per 100 000. This is likely due to the increased risk of endemic conditions such as malaria or neurocysticercosis; the higher incidence of road traffic injuries; birth-related injuries; and variations in medical infrastructure, the availability of preventive health programmes and accessible care. Close to 80% of people with epilepsy live in low- and middle-income countries.

Causes

Epilepsy is not contagious. Although many underlying disease mechanisms can lead to epilepsy, the cause of the disease is still unknown in about 50% of cases globally. The causes of epilepsy are divided into the following categories: structural, genetic, infectious, metabolic, immune and unknown. Examples include:

* brain damage from prenatal or perinatal causes (e.g. a loss of oxygen or trauma during birth, low birth weight);

* congenital abnormalities or genetic conditions with associated brain malformations;

* a severe head injury;

* a stroke that restricts the amount of oxygen to the brain;

* an infection of the brain such as meningitis, encephalitis or neurocysticercosis,

* certain genetic syndromes; and

* a brain tumour.

Treatment

Seizures can be controlled. Up to 70% of people living with epilepsy could become seizure free with appropriate use of antiseizure medicines. Discontinuing antiseizure medicine can be considered after 2 years without seizures and should take into account relevant clinical, social and personal factors. A documented etiology of the seizure and an abnormal electroencephalography (EEG) pattern are the two most consistent predictors of seizure recurrence.

* In low-income countries, about three quarters of people with epilepsy may not receive the treatment they need. This is called the “treatment gap”.

* In many low- and middle-income countries, there is low availability of antiseizure medicines. A recent study found the average availability of generic antiseizure medicines in the public sector of low- and middle-income countries to be less than 50%. This may act as a barrier to accessing treatment.

* It is possible to diagnose and treat most people with epilepsy at the primary health-care level without the use of sophisticated equipment.

* WHO pilot projects have indicated that training primary health-care providers to diagnose and treat epilepsy can effectively reduce the epilepsy treatment gap.

* Surgery might be beneficial to patients who respond poorly to drug treatments.

Prevention

An estimated 25% of epilepsy cases are potentially preventable.

* Preventing head injury, for example by reducing falls, traffic accidents and sports injuries, is the most effective way to prevent post-traumatic epilepsy.

* Adequate perinatal care can reduce new cases of epilepsy caused by birth injury.

* The use of drugs and other methods to lower the body temperature of a feverish child can reduce the chance of febrile seizures.

* The prevention of epilepsy associated with stroke is focused on cardiovascular risk factor reduction, e.g. measures to prevent or control high blood pressure, diabetes and obesity, and the avoidance of tobacco and excessive alcohol use.

* Central nervous system infections are common causes of epilepsy in tropical areas, where many low- and middle-income countries are concentrated. Elimination of parasites in these environments and education on how to avoid infections can be effective ways to reduce epilepsy worldwide, for example those cases due to neurocysticercosis.

Social and economic impacts

Epilepsy accounts for more than 0.5% of the global burden of disease, a time-based measure that combines years of life lost due to premature mortality and time lived in less than full health. Epilepsy has significant economic implications in terms of health-care needs, premature death and lost work productivity.

Out-of-pocket costs and productivity losses can create substantial burdens on households. An economic study from India estimated that public financing for both first- and second-line therapy and other medical costs alleviates the financial burden from epilepsy and is cost-effective.

The stigma and discrimination that surround epilepsy worldwide are often more difficult to overcome than the seizures themselves. People living with epilepsy and their families can be targets of prejudice. Pervasive myths that epilepsy is incurable, or contagious, or a result of morally bad behaviour can keep people isolated and discourage them from seeking treatment.

Human rights

People with epilepsy can experience reduced access to educational opportunities, a withholding of the opportunity to obtain a driving license, barriers to enter particular occupations, and reduced access to health and life insurance. In many countries legislation reflects centuries of misunderstanding about epilepsy, for example, laws which permit the annulment of a marriage on the grounds of epilepsy and laws that deny people with seizures access to restaurants, theatres, recreational centres and other public buildings.

Legislation based on internationally accepted human rights standards can prevent discrimination and rights violations, improve access to health-care services, and raise the quality of life for people with epilepsy.

WHO response

The 75th WHA adopted the Intersectoral global action plan on epilepsy and other neurological disorders 2022–2031, which recognizes the shared preventive, pharmacological and psychosocial approaches between epilepsy and other neurological disorders that can serve as valuable entry points for accelerating and strengthening services and support for these conditions.

Recently, WHO published an epilepsy technical brief, which outlines actions for policy makers and healthcare planners to reduce the burden of epilepsy in countries through finding and prioritizing the most effective solutions in a wide range of societal sectors.

WHO, the International League Against Epilepsy (ILAE) and the International Bureau for Epilepsy (IBE) led the Global Campaign Against Epilepsy to bring the disease out of the shadows to provide better information and raise awareness about epilepsy and to strengthen public and private efforts to improve care and reduce the disease’s impact.

These efforts have contributed to the prioritization of epilepsy in many countries and projects have been carried out to reduce the treatment gap and morbidity of people with epilepsy, to train and educate health professionals, to dispel stigma, to identify potential prevention strategies, and to develop models integrating epilepsy care into local health systems. Combining several innovative strategies, these projects have shown that there are simple, cost-effective ways to treat epilepsy in low-resource settings. The WHO Programme on reducing the epilepsy treatment gap and the mental health Gap Action Programme (mhGAP) achieved these goals in Ghana, Mozambique, Myanmar and Viet Nam, where 6.5 million more people have access to treatment for epilepsy should they need it.

Additional Information

Epilepsy is a chronic neurological disorder characterized by sudden and recurrent seizures which are caused by an absence or excess of signaling of nerve cells in the brain. Seizures may include convulsions, lapses of consciousness, strange movements or sensations in parts of the body, odd behaviours, and emotional disturbances. Epileptic seizures typically last one to two minutes but can be followed by weakness, confusion, or unresponsiveness. Epilepsy is a relatively common disorder affecting about 40 million to 50 million people worldwide; it is slightly more common in males than females. Causes of the disorder include brain defects, head trauma, infectious diseases, stroke, brain tumours, or genetic or developmental abnormalities. Several types of epileptic disorders are hereditary. Cysticercosis, a parasitic infection of the brain, is a common cause of epilepsy in the developing world. About half of epileptic seizures have an unknown cause and are called idiopathic.

In 1981 the International League Against Epilepsy developed a classification scheme for seizures based on their mode of onset. This work resulted in the formation of two major classes: partial-onset seizures and generalized-onset seizures.

Partial-onset seizures

A partial seizure originates in a specific area of the brain. Partial seizures consist of abnormal sensations or movements, and a lapse of consciousness may occur. Epileptic individuals with partial seizures may experience unusual sensations called auras that precede the onset of a seizure. Auras may include unpleasant odours or tastes, the sensation that unfamiliar surroundings seem familiar (déjà vu), and visual or auditory hallucinations that last from a fraction of a second to a few seconds. The individual may also experience intense fear, abdominal pain or discomfort, or an awareness of increased respiration rate or heartbeat. The form of the onset of a seizure is, in most cases, the same from attack to attack. After experiencing the aura, the individual becomes unresponsive but may examine objects closely or walk around.

Jacksonian seizures are partial seizures that begin in one part of the body such as the side of the face, the toes on one foot, or the fingers on one hand. The jerking movements then spread to other muscles on the same side of the body. This type of seizure is associated with a lesion or defect in the area of the cerebral cortex that controls voluntary movement.

Complex partial seizures, also called psychomotor seizures, are characterized by a clouding of consciousness and by strange, repetitious movements called automatisms. On recovery from the seizure, which usually lasts from one to three minutes, the individual has no memory of the attack, except for the aura. Occasionally, frequent mild complex partial seizures may merge into a prolonged period of confusion, which can last for hours or days with fluctuating levels of awareness and strange behaviour. Complex partial attacks may be caused by lesions in the frontal lobe or the temporal lobe.

Studies of temporal lobe epilepsy have provided important insight into the neurological overactivity that is frequently associated with seizures. For example, defects in neurons have long been suspected to underlie most forms of epilepsy characterized by excess brain activity. However, investigations of temporal lobe epilepsy have revealed that abnormal swelling of neuronal support cells known as astrocytes, which serve important functions in regulating neuron activity, may actually give rise to this form of seizure. As a result, astrocyte abnormalities have become of significant interest in understanding the pathology of other forms of epilepsy as well as other types of neurological disease.

Generalized-onset seizures

Generalized seizures are the result of abnormal electrical activity in most or all of the brain. This type of seizure is characterized by convulsions, short absences of consciousness, generalized muscle jerks (clonic seizures), and loss of muscle tone (tonic seizures), with falling.

Generalized tonic-clonic seizures, sometimes referred to by the older term grand mal, are commonly known as convulsions. A person undergoing a convulsion loses consciousness and falls to the ground. The fall is sometimes preceded by a shrill scream caused by forcible expiration of air as the respiratory and laryngeal muscles suddenly contract. After the fall, the body stiffens because of generalized tonic contraction of the muscles; the lower limbs are usually extended and the upper limbs flexed. During the tonic phase, which lasts less than a minute, respiration stops because of sustained contraction of the respiratory muscles. Following the tonic stage, clonic (jerking) movements occur in the arms and legs. The tongue may be bitten during involuntary contraction of the jaw muscles, and urinary incontinence may occur. Usually, the entire generalized tonic-clonic seizure is over in less than five minutes. Immediately afterward, the individual is usually confused and sleepy and may have a headache but will not remember the seizure.

Studies measuring electric currents in the heart have demonstrated that some patients affected by tonic-clonic seizures experience abnormal cardiac rhythms either during or immediately after a seizure. In some cases the heart may stop beating for several seconds, a condition known as asystole. Asystole has been linked to a phenomenon called sudden unexpected death in epilepsy (SUDEP), which affects more than 8 percent of epilepsy patients and typically occurs in people between the ages of 20 and 30. The cause of SUDEP is not known with certainty. Scientists suspect that accumulated damage and scarring in cardiac tissue, caused by multiple, recurring seizures, has the potential to interfere with electrical conduction in the heart and thus precipitate SUDEP during a typical tonic-clonic seizure. In addition, genetic defects associated with epilepsy and abnormalities in heart function have been identified in families affected by both inherited epilepsy and SUDEP.

Primary generalized, or absence, epilepsy is characterized by repeated lapses of consciousness that generally last less than 15 seconds each and usually occur many times a day. This type of seizure is sometimes referred to by the older term petit mal. Minor movements such as blinking may be associated with absence seizures. After the short interruption of consciousness, the individual is mentally clear and able to resume previous activity. Absence seizures occur mainly in children and do not appear initially after age 20; they tend to disappear before or during early adulthood. At times absence seizures can be nearly continuous, and the individual may appear to be in a clouded, partially responsive state for minutes or hours.

Diagnosis

A person with recurrent seizures is diagnosed with epilepsy. A complete physical examination, blood tests, and a neurological evaluation may be necessary to identify the cause of the disorder. Electroencephalogram (EEG) monitoring is performed to detect abnormalities in the electrical activity of the brain. Magnetic resonance imaging (MRI), positron emission tomography (PET), single photon emission computed tomography (SPECT), or magnetic resonance spectroscopy (MRS) may be used to locate structural or biochemical brain abnormalities.

Treatment

Most people with epilepsy have seizures that can be controlled with antiepileptic medications such as valproate, ethosuximide, clonazepam, carbamazepine, and primidone; these medications decrease the amount of neuronal activity in the brain. Brain damage caused by epilepsy usually cannot be reversed. Epileptic seizures that cannot be treated with medication may be reduced by surgery that removes the epileptogenic area of the brain. Other treatment strategies include vagus nerve stimulation, a diet high in fat and low in carbohydrates (ketogenic diet), and behavioral therapy. It may be necessary for epileptic individuals to refrain from driving, operating hazardous machinery, or swimming because of the temporary loss of control that occurs without warning.

Family and friends of an epileptic individual should be aware of what to do if a seizure occurs. During a seizure the clothing should be loosened around the neck, the head should be cushioned with a pillow, and any sharp or hard objects should be removed from the area. An object should never be inserted into the person’s mouth during a seizure. After the seizure the head of the individual should be turned to the side to drain secretions from the mouth.

It appears to me that if one wants to make progress in mathematics, one should study the masters and not the pupils. - Niels Henrik Abel.

Nothing is better than reading and gaining more and more knowledge - Stephen William Hawking.

Offline

Pages: 1