Math Is Fun Forum

You are not logged in.

- Topics: Active | Unanswered

- Index

- » This is Cool

- » Colloid

Pages: 1

#1 2025-12-08 17:02:44

- Jai Ganesh

- Administrator

- Registered: 2005-06-28

- Posts: 52,664

Colloid

Colloid

Gist

A colloid is a heterogeneous mixture where tiny, insoluble particles (1-1000 nm) of one substance (dispersed phase) are spread out in another substance (dispersion medium) without settling, like milk, smoke, or fog, characterized by particle size between solutions and suspensions, stability, and the Tyndall effect (scattering light).

A colloid is a mixture in which one substance consisting of microscopically dispersed insoluble particles is suspended throughout another substance. Some definitions specify that the particles must be dispersed in a liquid, while others extend the definition to include substances like aerosols and gels.

Summary

A colloid is a mixture in which one substance consisting of microscopically dispersed insoluble particles is suspended throughout another substance. Some definitions specify that the particles must be dispersed in a liquid, while others extend the definition to include substances like aerosols and gels. The term colloidal suspension refers unambiguously to the overall mixture (although a narrower sense of the word suspension is distinguished from colloids by larger particle size). A colloid has a dispersed phase (the suspended particles) and a continuous phase (the medium of suspension).

Since the definition of a colloid is so ambiguous, the International Union of Pure and Applied Chemistry (IUPAC) formalized a modern definition of colloids:

'The term colloidal refers to a state of subdivision, implying that the molecules or polymolecular particles dispersed in a medium have at least in one direction a dimension roughly between 1 nanometre and 1 micrometre, or that in a system discontinuities are found at distances of that order. It is not necessary for all three dimensions to be in the colloidal range…Nor is it necessary for the units of a colloidal system to be discrete…The size limits given above are not rigid since they will depend to some extent on the properties under consideration.'

This IUPAC definition is particularly important because it highlights the flexibility inherent in colloidal systems. However, much of the confusion surrounding colloids arises from oversimplifications. IUPAC makes it clear that exceptions exist, and the definition should not be viewed as a rigid rule. D.H. Everett—the scientist who wrote the IUPAC definition—emphasized that colloids are often better understood through examples rather than strict definitions.

Some colloids are translucent because of the Tyndall effect, which is the scattering of light by particles in the colloid. Other colloids may be opaque or have a slight color.

Colloidal suspensions are the subject of interface and colloid science. This field of study began in 1845 by Francesco Selmi, who called them pseudosolutions, and expanded by Michael Faraday and Thomas Graham, who coined the term colloid in 1861.

Details

A colloid is any substance consisting of particles substantially larger than atoms or ordinary molecules but too small to be visible to the unaided eye; more broadly, any substance, including thin films and fibres, having at least one dimension in this general size range, which encompasses about {10}^{-7} to {10}^{-3} cm. Colloidal systems may exist as dispersions of one substance in another—for example, smoke particles in air—or as single materials, such as rubber or the membrane of a biological cell.

Colloids are generally classified into two systems, reversible and irreversible. In a reversible system the products of a physical or chemical reaction may be induced to interact so as to reproduce the original components. In a system of this kind, the colloidal material may have a high molecular weight, with single molecules of colloidal size, as in polymers, polyelectrolytes, and proteins, or substances with small molecular weights may associate spontaneously to form particles (e.g., micelles, microemulsion droplets, and liposomes) of colloidal size, as in soaps, detergents, some dyes, and aqueous mixtures of lipids. An irreversible system is one in which the products of a reaction are so stable or are removed so effectively from the system that its original components cannot be reproduced. Examples of irreversible systems include sols (dilute suspensions), pastes (concentrated suspensions), emulsions, foams, and certain varieties of gels. The size of the particles of these colloids is greatly dependent on the method of preparation employed.

All colloidal systems can be either generated or eliminated by nature as well as by industrial and technological processes. The colloids prepared in living organisms by biological processes are vital to the existence of the organism. Those produced with inorganic compounds in Earth and its waters and atmosphere are also of crucial importance to the well-being of life-forms.

The scientific study of colloids dates from the early 19th century. Among the first notable investigations was that of the British botanist Robert Brown. During the late 1820s Brown discovered, with the aid of a microscope, that minute particles suspended in a liquid are in continual, random motion. This phenomenon, which was later designated Brownian motion, was found to result from the irregular bombardment of colloidal particles by the molecules of the surrounding fluid. Francesco Selmi, an Italian chemist, published the first systematic study of inorganic colloids. Selmi demonstrated that salts would coagulate such colloidal materials as silver chloride and Prussian blue and that they differed in their precipitating power. The Scottish chemist Thomas Graham, who is generally regarded as the founder of modern colloid science, delineated the colloidal state and its distinguishing properties. In several works published during the 1860s, Graham observed that low diffusivity, the absence of crystallinity, and the lack of ordinary chemical relations were some of the most salient characteristics of colloids and that they resulted from the large size of the constituent particles.

The early years of the 20th century witnessed various key developments in physics and chemistry, a number of which bore directly on colloids. These included advances in the knowledge of the electronic structure of atoms, in the concepts of molecular size and shape, and in insights into the nature of solutions. Moreover, efficient methods for studying the size and configuration of colloidal particles were soon developed—for example, ultracentrifugal analysis, electrophoresis, diffusion, and the scattering of visible light and X-rays. More recently, biological and industrial research on colloidal systems has yielded much information on dyes, detergents, polymers, proteins, and other substances important to everyday life.

Additional Information

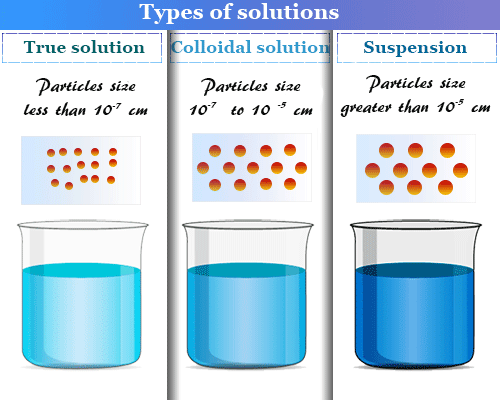

A colloid is one of the three primary types of mixtures, with the other two being a solution and suspension. A colloid is a mixture that has particles ranging between 1 and 1000 nanometers in diameter, yet are still able to remain evenly distributed throughout the solution. These are also known as colloidal dispersions because the substances remain dispersed and do not settle to the bottom of the container. In colloids, one substance is evenly dispersed in another. The substance being dispersed is referred to as being in the dispersed phase, while the substance in which it is dispersed is in the continuous phase.

To be classified as a colloid, the substance in the dispersed phase must be larger than the size of a molecule but smaller than what can be seen with the naked eye. This can be more precisely quantified as one or more of the substance's dimensions must be between 1 and 1000 nanometers. If the dimensions are smaller than this the substance is considered a solution and if they are larger than the substance is a suspension.

Classifying Colloids

A common method of classifying colloids is based on the phase of the dispersed substance and what phase it is dispersed in. The types of colloids includes sol, emulsion, foam, and aerosol.

* Sol is a colloidal suspension with solid particles in a liquid.

* Emulsion is between two liquids.

* Foam is formed when many gas particles are trapped in a liquid or solid.

* Aerosol contains small particles of liquid or solid dispersed in a gas.

When the dispersion medium is water, the collodial system is often referred to as a hydrocolloid. The particles in the dispersed phase can take place in different phases depending on how much water is available. For example, Jello powder mixed in with water creates a hydrocolloid. A common use of hydrocolloids is in the creation of medical dressings.

An easy way of determining whether a mixture is colloidal or not is through use of the Tyndall Effect. When light is shined through a true solution, the light passes cleanly through the solution, however when light is passed through a colloidal solution, the substance in the dispersed phases scatters the light in all directions, making it readily seen. An example of this is shining a flashlight into fog. The beam of light can be easily seen because the fog is a colloid.

Another method of determining whether a mixture is a colloid is by passing it through a semipermeable membrane. The larger dispersed particles in a colloid would be unable to pass through the membrane, while the surrounding liquid molecules can. Dialysis takes advantage of the fact that colloids cannot diffuse through semipermeable membranes to filter them out of a medium.

Tyndall Effect

The Tyndall Effect is the effect of light scattering in colloidal dispersion, while showing no light in a true solution. This effect is used to determine whether a mixture is a true solution or a colloid.

Introduction

"To be classified colloidal, a material must have one or more of its dimensions (length, width, or thickness) in the approximate range of 1-1000 nm." Because a colloidal solution or substance (like fog) is made up of scattered particles (like dust and water in air), light cannot travel straight through. Rather, it collides with these micro-particles and scatters causing the effect of a visible light beam. This effect was observed and described by John Tyndall as the Tyndall Effect.

The Tyndall effect is an easy way of determining whether a mixture is colloidal or not. When light is shined through a true solution, the light passes cleanly through the solution, however when light is passed through a colloidal solution, the substance in the dispersed phases scatters the light in all directions, making it readily seen.

It appears to me that if one wants to make progress in mathematics, one should study the masters and not the pupils. - Niels Henrik Abel.

Nothing is better than reading and gaining more and more knowledge - Stephen William Hawking.

Offline

Pages: 1

- Index

- » This is Cool

- » Colloid