Math Is Fun Forum

You are not logged in.

- Topics: Active | Unanswered

- Index

- » This is Cool

- » Rudder

Pages: 1

#1 Yesterday 19:27:25

- Jai Ganesh

- Administrator

- Registered: 2005-06-28

- Posts: 52,400

Rudder

Rudder

Gist

A rudder is a flat, vertical blade at the stern (rear) of a ship that controls its direction by deflecting water flow. When the rudder is turned, the force of the water against it pushes the stern away, causing the ship to turn in the opposite direction. It is operated by a steering wheel or tiller connected to a mechanical or hydraulic system, making it a crucial component for navigation and safety.

A rudder is a control surface used to steer a vessel or aircraft by changing the direction of the fluid (water or air) flowing past it, which in turn creates a turning or yawing motion. In ships, it directly steers the vessel, while in aircraft, it is primarily used to coordinate turns, correct for aerodynamic forces (like "adverse yaw"), and maintain stability, especially during crosswinds.

Summary

A rudder is a part of the steering apparatus of a boat or ship that is fastened outside the hull, usually at the stern. The most common form consists of a nearly flat, smooth surface of wood or metal hinged at its forward edge to the sternpost. It operates on the principle of unequal water pressures. When the rudder is turned so that one side is more exposed to the force of the water flowing past it than the other side, the stern will be thrust away from the side that the rudder is on and the boat will swerve from its original course. In small craft the rudder is operated manually by a handle termed a tiller or helm. In larger vessels, the rudder is turned by hydraulic, steam, or electrical machinery.

The earliest type of rudder was a paddle or oar used to pry or row the stern of the craft around. The next development was to fasten a steering oar, in a semivertical position, to the vessel’s side near the stern. This arrangement was improved by increasing the width of the blade and attaching a tiller to the upper part of the handle. Ancient Greek and Roman vessels frequently used two sets of these steering paddles. Rudders fastened to the vessel’s sternpost did not come into general use until after the time of William the Conqueror. In ships having two or more screw propellers, rudders are fitted sometimes directly behind each screw.

Special types of rudders use various shapes to obtain greater effectiveness in manoeuvring. The balanced rudder and the semibalanced rudder (see illustration) are shaped so that the force of the water flowing by the rudder will be balanced or partially balanced on either side of its turning axis, thus easing the pressure on the steering mechanism or the helmsman. The lifting rudder is designed with a curvature along its lower edge that will lift the rudder out of danger should it strike an object or the bottom.

Details

A rudder is a primary control surface used to steer a ship, boat, submarine, hovercraft, airship, or other vehicle that moves through a fluid medium (usually air or water). On an airplane, the rudder is used primarily to counter adverse yaw and p-factor and is not the primary control used to turn the airplane. A rudder operates by redirecting the fluid past the hull or fuselage, thus imparting a turning or yawing motion to the craft. In basic form, a rudder is a flat plane or sheet of material attached with hinges to the craft's stern, tail, or afterend. Often rudders are shaped to minimize hydrodynamic or aerodynamic drag. On simple watercraft, a tiller—essentially, a stick or pole acting as a lever arm—may be attached to the top of the rudder to allow it to be turned by a helmsman. In larger vessels, cables, pushrods, or hydraulics may link rudders to steering wheels. In typical aircraft, the rudder is operated by pedals via mechanical linkages or hydraulics.

Boat rudders details

Boat rudders may be either outboard or inboard. Outboard rudders are hung on the stern or transom. Inboard rudders are hung from a keel or skeg and are thus fully submerged beneath the hull, connected to the steering mechanism by a rudder post that comes up through the hull to deck level, often into a math. Inboard keel hung rudders (which are a continuation of the aft trailing edge of the full keel) are traditionally deemed the most damage resistant rudders for off shore sailing. Better performance with faster handling characteristics can be provided by skeg hung rudders on boats with smaller fin keels.

Rudder post and mast placement defines the difference between a ketch and a yawl, as these two-masted vessels are similar. Yawls are defined as having the mizzen mast abaft (i.e. "aft of") the rudder post; ketches are defined as having the mizzen mast forward of the rudder post.

Small boat rudders that can be steered more or less perpendicular to the hull's longitudinal axis make effective brakes when pushed "hard over." However, terms such as "hard over," "hard to starboard," etc. signify a maximum-rate turn for larger vessels. Transom hung rudders or far aft mounted fin rudders generate greater moment and faster turning than more forward mounted keel hung rudders. Rudders on smaller craft can be operated by means of a tiller that fits into the rudder stock that also forms the fixings to the rudder foil. Craft where the length of the tiller could impede movement of the helm can be split with a rubber universal joint and the part adjoined the tiller termed a tiller extension. Tillers can further be extended by means of adjustable telescopic twist locking extension.

There is also the barrel type rudder, where the ship's screw is enclosed and can be swiveled to steer the vessel. Designers claim that this type of rudder on a smaller vessel will answer the helm faster.

Rudder control

Large ships (over 10,000 ton gross tonnage) have requirements on rudder turnover time. To comply with this, high torque rudder controls are employed. One commonly used system is the ram type steering gear. It employs four hydraulic rams to rotate the rudder stock (rotation axis), in turn rotating the rudder.

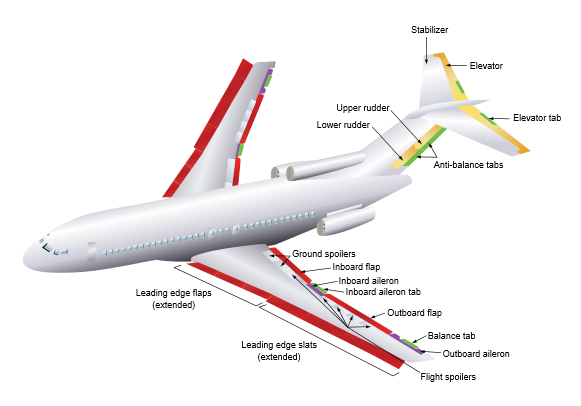

Aircraft rudders

On an aircraft, a rudder is one of three directional control surfaces, along with the rudder-like elevator (usually attached to the horizontal tail structure, if not a slab elevator) and ailerons (attached to the wings), which control pitch and roll, respectively. The rudder is usually attached to the fin (or vertical stabilizer), which allows the pilot to control yaw about the vertical axis, i.e., change the horizontal direction in which the nose is pointing.

Unlike a ship, both aileron and rudder controls are used together to turn an aircraft, with the ailerons imparting roll and the rudder imparting yaw and also compensating for a phenomenon called adverse yaw. A rudder alone will turn a conventional fixed-wing aircraft, but much more slowly than if ailerons are also used in conjunction. Sometimes pilots may intentionally operate the rudder and ailerons in opposite directions in a maneuver called a slip or sideslip. This may be done to overcome crosswinds and keep the fuselage in line with the runway, or to lose altitude by increasing drag, or both.

Another technique for yaw control, used on some tailless aircraft and flying wings, is to add one or more drag-creating surfaces, such as split ailerons, on the outer wing section. Operating one of these surfaces creates drag on the wing, causing the plane to yaw in that direction. These surfaces are often referred to as drag rudders.

Rudders are typically controlled with pedals.

Additional Information:

Description

The rudder is a primary flight control surface which controls rotation about the vertical axis of an aircraft. This movement is referred to as "yaw". The rudder is a movable surface that is mounted on the trailing edge of the vertical stabilizer or fin. Unlike a boat, the rudder is not used to steer the aircraft; rather, it is used to overcome adverse yaw induced by turning or, in the case of a multi-engine aircraft, by engine failure and also allows the aircraft to be intentionally slipped when required.

Function

In most aircraft, the rudder is controlled through the flight deck rudder pedals which are linked mechanically to the rudder. Deflection of a rudder pedal causes a corresponding rudder deflection in the same direction; that is, pushing the left rudder pedal will result in a rudder deflection to the left. This, in turn, causes the rotation about the vertical axis moving the aircraft nose to the left. In large or high speed aircraft, hydraulic actuators are often used to help overcome mechanical and aerodynamic loads on the rudder surface.

Rudder effectiveness increases with aircraft speed. Thus, at slow speed, large rudder input may be required to achieve the desired results. Smaller rudder movement is required at higher speeds and, in many more sophisticated aircraft, rudder travel is automatically limited when the aircraft is flown above Manoeuvring Speed to prevent deflection angles that could potentially result in structural damage to the aircraft.

It appears to me that if one wants to make progress in mathematics, one should study the masters and not the pupils. - Niels Henrik Abel.

Nothing is better than reading and gaining more and more knowledge - Stephen William Hawking.

Offline

Pages: 1

- Index

- » This is Cool

- » Rudder